“Two Beings Entwined”: A Mother-Daughter Memoir of Conflict and Healing

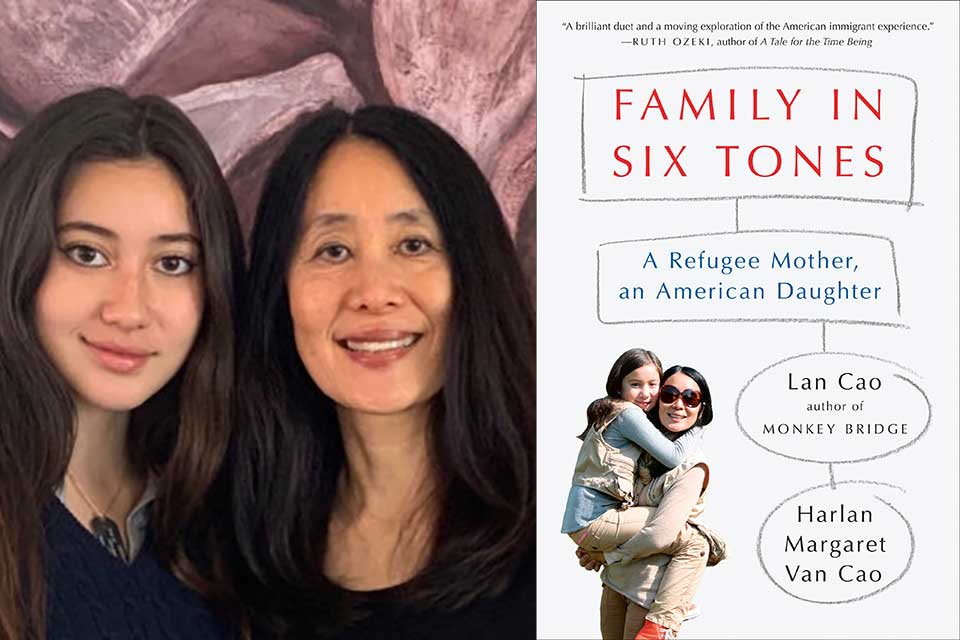

Family in Six Tones: A Refugee Mother, an American Daughter (Viking, 2020) is a memoir written in alternating narrative chapters between Lan Cao and Harlan Margaret Van Cao. Coming to the United States from Vietnam in 1975 as a thirteen-year-old refugee, Lan Cao forged her identity through education and academic achievement. An outstanding student growing up in Falls Church, Virginia, she graduated from Mt. Holyoke College and Yale Law School and began her career in corporate law. She turned to teaching and scholarship at Brooklyn Law College, William & Mary Law School, and Duke University Law School. Currently, she is the Betty Hutton Williams Professor of International Economic Law at the Chapman University School of Law. Cao is also the author of two novels: Monkey Bridge (1997) and The Lotus and the Storm (2014). Her daughter, Harlan, is a freshman at the University of California Los Angeles. Born in Williamsburg, Virginia, she moved to southern California when she was ten. At UCLA, she plans to study economics and philosophy, while continuing to write with a special interest in film scripts. She hopes eventually to lead a film production company profitable enough to support endangered species. As these “two beings entwined,” Cao writes, and “clash and boomerang” through each other’s lives, they celebrate that most complex of generational bonds and remind us that “the stories that need to be told are the hardest ones to tell.”

The following interview is based on a Zoom session with both mother and daughter on September 3, followed by individual email communication.

Renee Shea: As I understand it, the genesis of Family in Six Tones is an interview the two of you did for StoryCorps in 2014 when Harlan was twelve. Although it never ran in full, in 2018 on the fiftieth anniversary of the Tet Offensive, a portion of it aired on National Public Radio. Someone from Viking heard it, thought you two have a chemistry and a unique perspective on what it means to be an American, and approached you about a book. Did you hesitate at all in saying yes?

Harlan Margaret Van Cao: I didn’t …

Lan Cao: I did.

Harlan: She hesitated because she’s a lot more private. She didn’t want to come out from behind fiction or law reviews and do a book about herself. There was kind of a debate in the family, but, honestly, I’m not a good risk assessor, so I just wanted to try it—to have the experience.

Lan: Harlan has always liked to write, so it was natural for her. I hesitated because it’s a memoir. Also because I rarely do collaborative work—one time I wrote a short law review article with a colleague about a joint project we did. And Harlan is a teenager, so I foresaw a lot of stumbling blocks. Finally, I thought, “Why not?”

Harlan: Honestly, I knew we would fight anyway. But the fights molded the book, so it feels like there was a purpose, something worthwhile. I knew I was at the age when you’re going to fight with your mom the most. But at least with the book, it would be important.

Shea: How do you define your “roles” in this collaboration? Who came up with the overall structure of alternating voices in each chapter?

Lan: We had a general chapter-by-chapter road map from Viking, but we digressed—it wasn’t all plotted out. The individual writing process was very introverted; then we would have bursts of outward interaction. Those tended to be fireworks—I didn’t want this in, she thought it must be in, I didn’t like how she described certain things. … So there was that shaking up of the writing process. Then where there was more of an interface, it was not always a good experience. I even had to call our agent privately and say there are a lot of problems, but she assured me that any collaboration creates problems.

Harlan: She would drive me to school in the morning, when I’m already upset because it’s so early—and then we would fight when I’m just waking up. The writing put me in a shell—not in a bad way. The problem was that I didn’t have a good idea of what’s appropriate or what’s not. Maybe I was at a defiant age. It was only a year ago—and I’m talking like it’s twenty years!

Shea: You’ve commented that your personalities—Harlan the extrovert, Lan the introvert—show in your writing. What does that mean?

Lan: When we wrote, we both went into an introverted space, meaning we didn’t start out interacting and saying this is what we’re going to do. In that sense, we reverted to our cocoon selves. I was always nervous because I never even saw her write; I thought, “There are deadlines and are you even doing the work?” She’s a night owl, so probably she was writing at two in the morning. We’d only interact in snippets: she might mention something, and I’d know she was writing.

Harlan: When Viking offered me this deal, they caught me at a time when I really needed to get things off my chest. So maybe at first I treated the book too much almost like a hormonal dumping ground—and as I got older, I had to clean it up slowly because it got closer to the release date.

Lan: When we would actually finish our respective sections and discuss them, we met in the extrovert space—a shared space where there’s lots of activity explaining, defending certain things that were included or included. When you’re working with your kid who objects to a lot of things, the sparks that fly are hyperkinetic. It’s like coming out of hibernation into an energy storm!

“When you’re working with your kid who objects to a lot of things, the sparks that fly are hyperkinetic.”—Lan Cao

Shea: Harlan, you’ve called this book “kind of a confession.” To whom? To your mother? Yourself? Readers?

Harlan: I didn’t really think about who I’m confessing to. If I am going to confess something, it’s more like releasing a certain energy. Anyway, I think my mom knew a lot of it.

Lan: There were things I didn’t know. I knew she was going through some really hard periods in high school. But it was a different kind of difficulty. My experience was more like ostracism, not having friends, whereas she had a lot of people around her, so the isolation, which was much deeper than I ever thought, came from being part of a group. I didn’t see the undercurrent, which I only discovered from writing the book.

Shea: Harlan, writing this book took place over some tumultuous years, including the illness and death of your father, William Van Alstyne, a brilliant legal scholar. Were you ever tempted to let the project go in light of the emotional intensity of this experience?

Harlan: I knew that the last thing he had seen me doing was working on this book, so even though a piece of my creativity died with him, his death was a propeller to doing well and telling the story of our family. I wasn’t writing fiction, though, where I could escape this depressive world of mourning; I was writing a nonfiction story based on my life with my mother and father while he was leaving my life. But it truly never occurred to me to quit the project despite how much I worship him—or maybe it was actually because of it, not despite it.

Shea: Lan, you explain in the book that there are “six tones” in the Vietnamese language. How did you settle on that as your title?

Lan: I’ve always been really bad at titles, and this one came after the fact, just like the titles of my novels. One of our editors came up with a title about two animals from one of Harlan’s chapters. Harlan was concerned that animals might sound like a children’s book. Also, with the two animals, it could sound like a geopolitical book (i.e., Russian bear). But then this editor, who’s really good, came up with that title—and I loved it immediately because “six tones” shows something very particular to the Vietnamese language. You have to have a sharp ear to hear the differences, so these six tones are a lyrical way to refer to the language. I love the musicality of it because it’s like a scale in a song: changing one note can produce a totally different effect.

Harlan: One mistake can change the meaning of a whole sentence. So I think it could also be an allusion to how fragile the mother-daughter relationship is. Especially if you have a mom who has a memory like an elephant; little things can change an entire day for us.

Lan: I love that the title is not explicit: the explicitness comes from the subtitle. As Harlan says, a small shift can create a huge change. When I raised Harlan, the main thing I wanted to impart to her is going against the grain of the one tone that I feel is dominant in American culture—I want the six tones of Vietnamese culture. In many ways Western culture, American in particular, prizes individuality and competition: I clean the bathtub if I make the mess; if I do my house chores, I get my allowance. That’s a very individualistic way of how the child fits into the family framework. In Vietnam, there is no such thing. You live in the house, you are with five other tones—you’re just going to do it; it’s not transactional.

“When I raised Harlan, the main thing I wanted to impart to her is going against the grain of the one tone that I feel is dominant in American culture—I want the six tones of Vietnamese culture.”—Lan Cao

Shea: As many memoirs do, yours touches on sensitive topics, often revelations. Some of the more provocative issues—such as the “shadow selves”—are only hinted at. Why would either of you bring up these issues if you were uncomfortable sharing or addressing them more fully?

Lan: The “shadow selves,” a Jungian term, refers to a tacit understanding that there is a self in all of us that we don’t even know. Everyone, unconsciously, has shadow selves. There are a lot of crevices, like in life, where things are underneath the stone. So yes, it was left kind of ambiguous. Two people can undergo the same event—and have a totally different reaction. In Vietnam, my father had over fifty experiences on the battlefield, whereas I had more experiences sort of parachuting in and out of military hospitals where my mother worked. These different experiences created very different imprints on us. For me, the trauma has created a kind of dissociation, which in some cases was really pronounced—so those are my shadow selves. I’ve been dealing with this one issue for almost fifteen years in therapy.

Shea: Yet in the book, you say that you’ve come to see them as “guardian angels.”

Harlan: They work for her—it’s not a handicap.

Lan: The shadows are there, but they are integrated, folded naturally, more harmoniously. When I went into therapy, Harlan was really concerned because she loves them. We debated about including them. My editor, whom I’ve known since 1997, and I decided it’s important to destigmatize these issues—and be bold about it. Law is all about rationality and is totally integrated, and, well, it’s nice (a euphemism) to dip your toe into uncharted waters. But my personality and style of writing has always been a kind of French filmmaking rather than Hollywood—less explicit, more suggestive.

Harlan: Especially for a memoir, implying for me is not just the safest route to take—you’re not exposing yourself as much. Because I’m so young, I don’t want to seem like I’m speaking in an entitled way, so it’s better to imply, and I like it as a writing style. Our biggest problem was that things I wanted to put it in, she didn’t. We had a lot of people advising us, and the compromise at the end of the day was that implying was the smartest way to go. Sometimes I felt a disconnect—because we never wrote together—but these were parts we discussed and compromised on.

Shea: Lan, are the shadow selves for you, then, part of the refugee experience?

Lan: The shadow selves came out exactly the way we wanted. It’s concrete enough but leaves enough open that the experience is more universal. You’re not just describing a little pock mark on a specific table; you’re discussing how to live with damage, how to live with flaws, with scars, because every single person in the world has gone through something they are trying to come to terms with. It’s the human experience. As human beings we all want to be known, to be understood, but we worry that once we reveal that part to a close person, will they accept us. So the shadow self—whatever it is we have as our hidden self—do we dare expose it?

When refugees and immigrants arrive in a new country, it is totally a pioneering unknown. They’re going to ask themselves, “What do we need to assimilate and what do we maintain as a part of ourselves?” This is a big debate in American identity and a very personal and sometimes painful process. “Assimilation” is not as smooth as the term makes it sound—a soft sibilant sound—and it’s deceptive because it’s actually a very violent process. I’m trying to say that even immigrants who assimilate have a shadow self, or selves, that they don’t show to the mainstream.

Shea: Harlan, in her introduction to the memoir, your mother writes that she wanted to give you what she has never been able to achieve for herself: wholeness. Has she? Or is it too soon to tell?

Harlan: To a point, yes. But there is a part of me that is divided between being a “normal” teenager and this cultured and conscientious adult my mother made me into from a young age. Any divide I have felt within myself had nothing to do with being half-Vietnamese, half-white. It had everything to do with trying to handle things at home like her “shadow selves” while at the same time going to parties and making friends like everyone else my age. I think she’s right, though, when she says I am “unhyphenated” because I’ve always been sure of who I am.

“I think my mom is right, though, when she says I am ‘unhyphenated’ because I’ve always been sure of who I am.”—Harlan

Shea: So you’ve written about what often feels like your mother’s overprotectiveness. And yet, what about that message she sent after the two of you had a pretty rigorous argument? In the middle of the night, she texted an iconic photo with this message: “This is an image of a class of boys all doing the Heil Hitler salute. Look at the right bottom corner. Only one boy is refusing to raise his arm. Be that boy.” Are you that independent boy?

Harlan: I think I am that boy—or at least I like to think I am. I’ve never been in a situation like that where it is so black and white, so I can only speak for what I hope I would do. The funny thing is, my mother feels like she’s never done reminding me to be a good person—even if I was Malala or Gandhi, she’d send me that!

Shea: What about your mother as a parent do you imagine you might pass on when you’re a mom?

Harlan: I think she’s very good in showing me the world, but I’m not sure I’d do that so early just in terms of knowing everything that can go wrong. The childhood innocence is very important to me, so I might compromise that a little bit. But even though my mother wants to prepare me for everything, she was never controlling about things like which friends I can see: it was always just get your homework done first. That made me definitely not as two-faced as others whose parents were very strict. So I’ve seen that giving a child a certain amount of freedom is very important, but when it comes to the deeper relationship, I really want to be close to my kid (if I have a kid) to the point where he or she wouldn’t feel a need to hide anything from me.

Shea: Lan, you’ve described the book as “a kind of love story to America.” But that story is complicated (“sometimes a protagonist in my life, sometimes an antagonist”). How do both of you think that perspective is likely to play in today’s political environment?

Lan: I think people like you would already embrace it because it’s not just in your framework but inside your body—you embrace it from within, not like a structure outside there. But I think the memoir will also reach people who are more along the other spectrum because the way we tell the story is like a love letter. The patriotic Americans in the traditional sense would find appeal in this book because it tells you that even if there are gullies in American history, there are still very beautiful things that continue to draw people to this country. People all over the world continue to be drawn to America; it’s not like they’re risking their lives to go to other powerful countries, like Russia. What’s happening now is a subversion of an aspect of America that both parties have always accepted. We’re talking about the American values of equality and freedom. Whether you’re Republican or Democrat, you may see different policies that the government can take to get to those values, but immigration is in the DNA of this country. Whether there are too many, whether the borders should be secured differently, you can talk about those as policy matters. The basic values remain.

Our memoir shows us as immigrants and refugees and our love for the country and our ability to point out that the country is not acting as it has promised. Making a promise is important because it makes you better. So I think the book should resonate with people from all spectrums if they look at it with the love we’ve put into it. It’s an American story.

Harlan: The way we comment on immigration is by telling our story. I was always careful in the book not to comment explicitly but to tell the story. I talk about my mother, she worked her way up, she’s successful—but I don’t comment in a way that judges anybody. I didn’t want to write an article on current affairs.

Shea: Lan, in “Vietnam Wasn’t Just a War,” a 2018 New York Times op ed, you write that “the Vietnam War remains, for Americans, essentially an American experience, or more accurately, an American metaphor.” In what ways, if any, do you think that Family in Six Tones is a way to continue that conversation with Harlan’s generation?

Lan: I do see the book as continuing the conversation with both the next generation of Americans and also the next generation of Vietnamese Americans. Most Vietnamese parents here do not talk about Vietnam or the war with their children. They tend to be silent sufferers, taught to bear and sacrifice in private and without complaint. And they are ashamed they lost, so they feel they should be appropriately mute. Their children actually have little firsthand knowledge of Vietnam and tend to learn about it from Americans who take a very U.S.-centric view of Vietnam and the war. That to me is like a Vietnamese kid growing up with dolls that are blond and have blue eyes—having your sense of self-worth defined by other people’s standards. Because I know that most Vietnamese of my parents’ generation don’t share their grief or history with their children, I am hoping that this book will be a bridge for Harlan’s generation to connect with their parents.

Shea: Harlan, your mother wrote, “Your success is your parents’ American Dream.” That’s certainly true of first-generation immigrants, but do you think it’s also true for you?

Harlan: Fourteen-year-old Harlan would have said no because at that time I was resentful of how (to me) she would sacrifice our relationship and my emotional well-being for straight A’s, piano recitals, etc. But, as my boyfriend recently said, I am my mom’s successor, which means my success is hers. Her way of success was to work very hard and keep her head down without distractions. I think that I’m able to get things done by being strategic and smart about it because of her extra work. So, yes, I feel my achievements will always be hers.

“I am my mom’s successor, which means my success is hers. Her way of success was to work very hard and keep her head down without distractions. I think that I’m able to get things done by being strategic and smart about it because of her extra work.”—Harlan

Shea: Now—finally—it’s about two weeks from the book’s publication, how do you feel?

Harlan: I feel a little anxious about people reading it. Maybe they’ll get the completely wrong idea about what I was trying to say, or I might offend someone. I didn’t think I’d have that experience so young.

Lan: For me, it’s very similar to the process I’m going through with Harlan now. She just turned 18—so that is like having finished a book. There’s nothing anymore I can prevent her from doing; I can only give advice. Once you’ve written a book, you relinquish it. I have never gone back and reread my novels or even law review articles. So, even though this work is more personal, I feel like I’m finished; it’s out there in the world, just like she’s going to be out in the world with her own trajectory.

September 2020