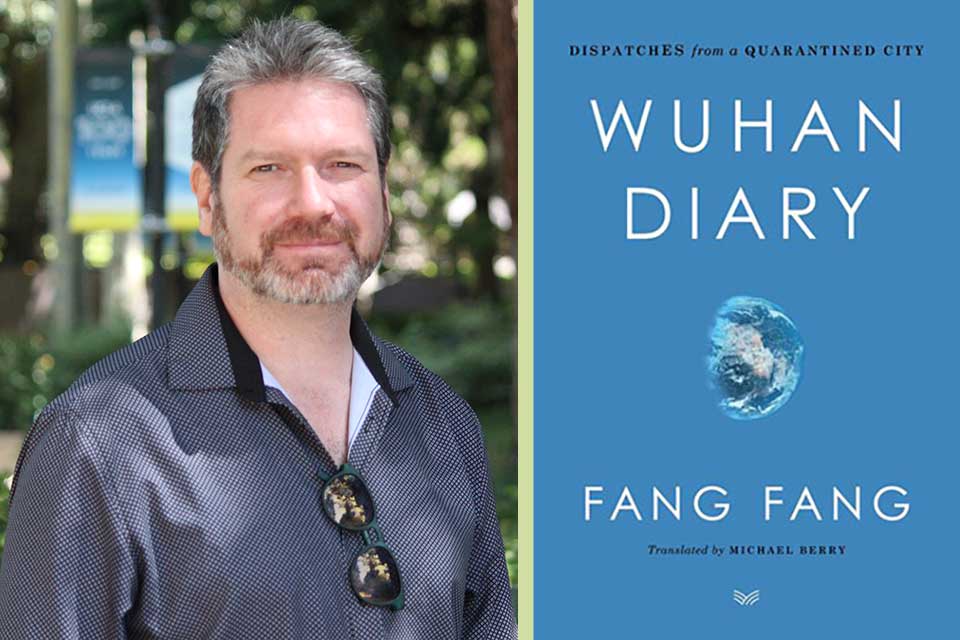

Translating Fang Fang’s Wuhan Diary amid the Covid-19 Pandemic: A Conversation with Michael Berry

Michael Berry is a professor of Asian languages and cultures and director of the Center for Chinese Studies at UCLA. He has published extensive works on addressing the richness and diversity of Chinese art and culture in sinophone communities. He is also an award-winning English translator of several Chinese literary works, including Yu Hua’s To Live (2003), Wang Anyi’s The Song of Everlasting Sorrow: A Novel of Shanghai (2008), Wu He’s Remains of Life (2017), and Fang Fang’s Wuhan Diary: Dispatches from a Quarantined City (2020). Recently, he has been invited by Yale University, Duke University, University of Pennsylvania, and Washington University in St. Louis to give lectures on Fang Fang’s Wuhan Diary.

In this conversation with King Yu, Berry discusses the process of translating Wuhan Diary, in which he encountered unusual challenges outside of the text.

King Yu: How did you become aware of Fang Fang’s Wuhan Diary (2020)? And how did the project of translating her diary come into being?

Michael Berry: I had met Fang Fang over the internet about two years ago, roughly around 2018. A mutual friend introduced us, and we discussed the possibility of me translating her novel Soft Burial, which is how I first got to know Fang Fang. Eventually we decided to go ahead on that project. I actually produced a sample translation and put in a grant application for Soft Burial in 2019. I was actively working on that project when the coronavirus broke out. I knew that Fang Fang lived in Wuhan, so I was very concerned about her. I reached out to her several times to check in and see how she and her family were doing. We exchanged numerous texts, but she never mentioned the diary. I had seen it on my Weibo feed, but I didn’t initially realize the impact that it was having, and she never mentioned it.

It was actually in early February 2020 during a phone call with my former supervisor, David Der-wei Wang from Harvard University, that he mentioned it. He asked if I was reading her diary. I told him that I had glanced at it but didn’t really examine it in any detail. He said: “You should really take a close look at it.” So that night I read just one or two entries, and I was really blown away. Almost immediately, I thought I should probably put Soft Burial aside and work on this diary instead. I immediately wrote to Fang Fang. I asked her if she was comfortable with that. Actually, she said no. She said that the diary was not complete and the coronavirus outbreak was still ongoing. She just thought it was premature; “Let’s just think about it and come back to this.” So that was where it began.

This, early on, felt like another SARS-like moment that could have really far-reaching ramifications.

Yu: So, in fact, you just read a few entries and she was still writing at that time. Why did you think translating Fang Fang’s Wuhan Diary was so important then?

Berry: Well, just like SARS in 2003. We all know the SARS outbreak became a major global moment. It had incredible reverberations, not just in China but in Hong Kong, Canada, and elsewhere, affecting many people. This, early on, felt like another SARS-like moment that could have really far-reaching ramifications, although I certainly didn’t realize it was going to spread like it did and shut the world down at that point. But even if it was just limited to Wuhan, Hubei Province, it was still having an incredible impact and was becoming a kind of touchstone moment.

Up to that point, I had been following the stories about the outbreak on Sina, Chinese media as well as foreign media. But what you get in a typical media coverage, 500- or 1,000-word news stories, tends to be very superficial. When I was reading Fang Fang’s diary, it was much more. It was a long-form narrative, so she could go much deeper and into much more detail. At the same time, it also had a more humanistic approach because she is a writer—she was able to put a human face on what was happening. Through her diary you not only vicariously experience what was happening, you also get a glimpse inside into her emotional state. You can see her fear, anger, and all the other emotions she was going through as she was living through what, at that time, was a completely unique experience. Hence, it just felt like an incredibly important narrative to get out and to the world. If, in the event it did spread to America, Canada, and Europe, I felt this would be a very important document in terms of what we can learn from the Chinese response to Covid-19. In so many ways, it just felt like it was an account of the moment, and it was very important to get it out and in very timely fashion.

Yu: In this sense, at the beginning, you wanted to deliver this information about how the coronavirus had broken out in China at that time. In fact, it seems like some kind of crisis translation, trying to disseminate the information to help people around the world and let them know what was happening in China and what the coronavirus was like at that stage.

Berry: Yes, I think that’s fair to say. Also, it had to do with the fact that Fang Fang’s diary was becoming a major cultural text. Very quickly, it had millions of readers. So, it was not just about the coronavirus but also Fang Fang’s testimony and account, which I felt was going to be an important testimony for the world and for history to look back upon. It was already going viral all over the Chinese internet. Tens of millions of people were reading it. It was becoming an incredibly important cultural intervention into what was happening. I thought that her message and voice would have ramifications beyond just China and elicit global interest.

Yu: HarperCollins is one of the most outstanding publishing houses in the English world. With regard to the translation of Chinese literature, it is often very difficult to find an English publisher. In this context, I wonder, how did you manage to get HarperCollins to publish Fang Fang’s diary?

Berry: As soon as I decided that I wanted to work with Fang Fang on this diary. I knew this was a story that would have a widespread appeal globally. What was happening in Wuhan was such an important moment. During that early phase from late January to early February, it really felt like we were witnessing a snowball effect as the impact of Covid-19 spread wider and wider. And even without the global context, what was happening in Wuhan was already quite unprecedented; it was still a huge story. For many, there was also an almost ominous sense that something was coming. From that perspective, Wuhan Diary is also an incredibly important testimony, not only about what had happened, but also what was to come.

In any case, because I knew there was potential for greater interest in this book, I reached out to a literary agent. I thought this book needed somebody to steer the ship; it needed someone with experience with commercial publishing houses. So, as soon as Fang Fang agreed to work with me, I asked her if she would mind if I brought an agent in to represent her and the book, because I felt the project called for that. She agreed. Hence it was through the agent that the book was placed with HarperVia.

It really felt like we were witnessing a snowball effect as the impact of Covid-19 spread wider and wider.

Yu: As we know, the initial title and the description of her diary for presale on Amazon were controversial but were later revised. How did that happen?

Berry: The title that Fang Fang had approved after a lot of back and forth was “Wuhan Diary.” That’s it. We didn’t discuss any subtitle. When the cover design appeared, the publishers added a subtitle that said, “Dispatches from the Original Epicenter.” I had forwarded that cover design to Fang Fang, but I did not translate the subtitle. Part of the reason is just that it didn’t raise any red flags for me when I read the title. A big part of the controversy is, again, an issue of translation. My interpretation of “original epicenter” was that there were many epicenters for Covid-19: Washington State and New York later both became epicenters in the US; northern Italy became an epicenter in Europe; Los Angeles is now the epicenter, etc. The “original” just means that Wuhan was the site of the first major outbreak of Covid-19. That was my interpretation of the publisher’s subtitle.

It seemed as if Fang Fang’s diary entries were coming from the future.

The people who were attacking the book tried to interpret the subtitle as if the author, translator, and publisher were intentionally trying to make a statement about the scientific origins of the virus. They specifically pointed out the fact that the word “origin” was tied to the word “original,” which appeared in the subtitle. This was a politicized interpretation, which, to the best of my knowledge, was 100 percent inaccurate. I didn’t come up with that original subtitle, so I can’t speak entirely for the intentions of the publisher. But I certainly do not believe there were any nefarious political motivations at work. Actually, when I was translating the book, I sent the editor chapters as I was working, and at one point he sent me an email: “Wow, if it is going to be published today, I would add the subtitle ‘Dispatches from the Future.’” Because it seemed as if Fang Fang’s diary entries were coming from future. At that time, the outbreak in New York was just starting to get worse, and the New York–based editor felt like he was seeing into the crystal ball of what was coming. So that’s where the notion of “dispatches” came. Consequently, when the publisher decided to use “the original epicenter,” it didn’t initially raise red flags with me.

It was also very early in the overall production process. There had not even been a formal press release about the book yet—all that came later. There was nothing formal at that point. However, without consulting me and Fang Fang, the publisher’s sales department uploaded presale pages to Amazon and other online booksellers with that subtitle and a description of the book that no one had yet vetted. None of us saw that initial description; not my agent, Fang Fang, or me. The reason the publisher put that information out early was because the book was on a rush schedule and they had an internal deadline to meet in terms of getting presale information out on the various online websites.

When we saw the description, both Fang Fang and I raised objections. And as soon as that early title and description were uploaded, the online controversy exploded almost overnight. I discussed everything with Fang Fang, and we immediately asked the publisher to revise the title and description. It took a few days, but after the author and I, along with our agent, expressed our views, the publisher agreed. The process only took about a week, and all of the online descriptions were updated.

Yu: It is worth noting that both Fang Fang and her diary have received fierce attacks online, and even you have tasted a little bit of that. In light of this pressing situation, has the Chinese public attitude toward Fang Fang and her diary had any impact on your translation?

Berry: By the time the attacks began in April 2020, the translation was nearly complete. From 7 April to 10 April, the attacks were really bad. The translation was finished around 14 April or 15 April. So, I was already at the very final stage of the project by then. I just had to put that out of my mind and push through to finish it. Had I not been so far along, I’m sure it would have had a stronger impact on me because it was a kind of psychological terrorism. It was hard to do anything. When you open your computer and find thousands of threats—death threats, personal attacks, vulgar misrepresentation of you as a person, you as a scholar and your work—it certainly has an impact. But by then I was almost through with the project. I just had to focus and push forward to finish the translation. But it did make me very conscious of making sure my translation was airtight, and that it was as faithful, accurate, and above any type of criticism as possible. I knew from the attacks that there were forces looking for holes and errors in my translation to attack the book. That was part of their strategy as well. It made me more conscious of trying to ensure the quality of the translation.

I knew from the attacks that there were forces looking for holes and errors in my translation to attack the book.

Yu: In America, editors often play a very important role in translation. In this regard, I’m curious about what role the editor played in the case of the translation of Fang Fang’s diary.

Berry: Normally, in my past experiences with commercial presses, editors from commercial publishing houses can be extremely hands-on. There are even examples from US editors requesting the author to write a new conclusion to a book, as was the case with one of Mo Yan’s novels. I also had some early experiences with editors that were more hands-on, which at times made me a little uncomfortable.

But this time, probably because of the attacks, the publisher was extremely respectful; they took a more hands-off approach that allowed Fang Fang’s original vision to be fully realized. At one point, we did discuss doing an abridged version, but they tabled that idea. During the copyediting, I think the basic perspective was not to tamper at all with the content and make sure the translation was rendered into clear and proper English. There was absolutely no tampering and meddling while she was writing or after she delivered the final manuscript.

Yu: You are an active translator of Chinese literature, having brought Chinese works by writers such as Yu Hua, Wang Anyi, and, recently, Wu He to the English world. I wonder whether there are any differences between translating their works and Fang Fang’s diary? Have you faced any particular challenges in translating her diary?

Berry: Yes. The challenges were very different than anything I have ever encountered before. For instance, Wu He’s novel Remains of Life was written in a stream-of-consciousness format, experimenting with different dialects and narrative approaches. In some ways, I found the technical side of translating this book by Fang Fang to be like breathing fresh air, almost like translating Qiong Yao or a writer like that. It was just simple prose, straightforward, unadorned, without any experimental language or allegorical dimensions. The actual translation was very straightforward. It was very matter-of-fact prose.

The challenges I faced had more to do with my own stamina, just translating that much in such a short period of time: sleep deprivation, aching tendons in my arms and hands from typing so much, blurry vision from staring at the computer for so long. Those were the challenges. And later, there were the psychological challenges of the incessant death threats and attacks. Those were very unique challenges to this project. In terms of the technical translation issues of the actual content, there wasn’t much there. There were only a few passages where I needed to write to Fang Fang for further clarification, but there were very few of those. Overall, the prose was pretty straightforward.

November 2020