Showcasing Poems That Present the Palestinian Narrative: A Conversation with Naomi Foyle

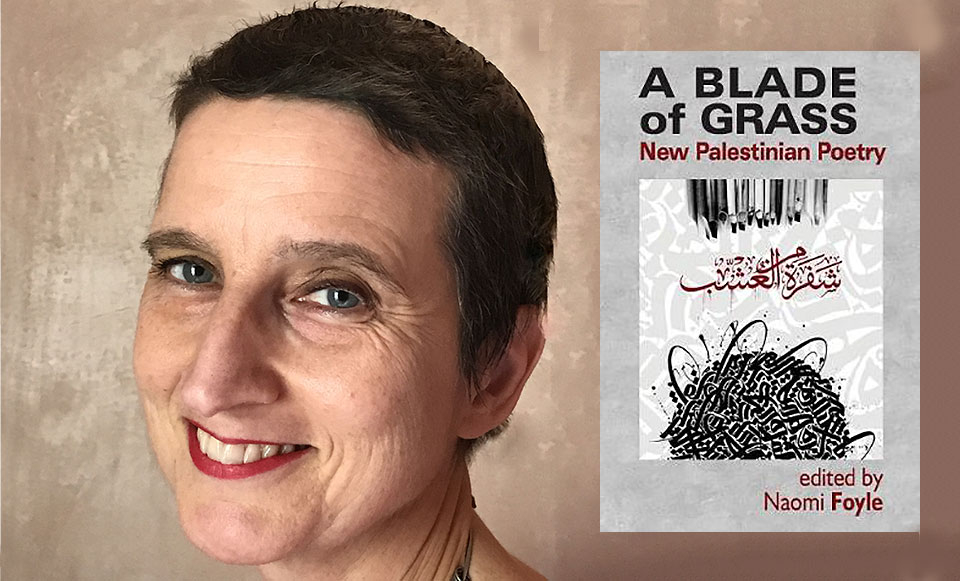

Naomi Foyle (naomifoyle.com/wp), editor of A Blade of Grass: New Palestinian Poetry, discusses curating the project, her battle with cancer, and the power of poetry. She teaches creative writing at Chichester University, and has edited thirteen full-length poetry collections. An activist for a just peace in the Middle East, Foyle participated in the Gaza Freedom March in 2009. Her many publications include five novels, two poetry collections, and a short theatrical piece produced by the Bush Theatre in 2011.

Valentina Viene: How did you conceive the idea of a Palestinian poetry collection?

Naomi Foyle: The idea came from Andy Croft of Smokestack Books, whose dedicated commitment to radical internationalist poetry I admire enormously. I met Andy four years ago at the launch of Judith Kazantzis’s collection, Sister Invention, which he’d published in part for its sharp-eyed poems on Palestine. Judith and I, along with her late husband, Irving Weinman, co-founded British Writers in Support of Palestine (BWISP) in 2010 and had worked together on letter-writing campaigns in support of the cultural and academic boycott of Israel.

Knowing of this political activity, Andy asked me if I’d like to edit a bilingual anthology of Palestinian poetry in translation. I jumped at the chance, on condition I could do the job after my science fiction novel writing contract was finished and that Smokestack Books—which receives no public subsidy and was not able to pay me or contributors—would help me run a crowdfunding campaign in order to pay the poets and translators a small fee. Andy was very happy with this plan, as we both were in 2015 when the project got a boost in the form of a research development award from the University of Chichester, funding that ensured I could guarantee a base payment to the contributors.

In 2016 things took a desperately uncertain turn when I was diagnosed with breast cancer, but after ten months of highly successful treatment, thankfully ,I ended up editing the anthology and finishing the last novel in my SF series simultaneously—not the plan, and a rather hectic autumn, but also a great, roaring return to life.

Writing poetry is a lifeline, and the poetry I love the best has a sense of absolute necessity about it.

Viene: Where does the title come from?

Foyle: Again, all credit to Andy Croft. A Blade of Grass is a phrase from a Mahmoud Darwish quote, which Andy came across in an interview with the great Palestinian poet conducted by Nathalie Handal in 2006. Handal presented Darwish with one of his own sayings: “Against barbarity, poetry can only resist by cultivating an attachment to human fragility, like a blade of grass growing on a wall while armies march by.” When asked if he still believed that, Darwish responded: “I thought poetry could change everything, could change history and could humanize, and I think that the illusion is very necessary to push poets to be involved and to believe . . . but now I think that poetry changes only the poet.”

I think he was being too modest, though. As Darwish’s own phenomenal popularity demonstrates, readers too need poetry to refresh, restore, and reinvent ourselves. His quote, to me, speaks of poetry’s inexhaustible strength—a distillation of the human spirit, poetry is at once as humble, frail, and perennial as the grass. To authoritarian regimes, it’s a poisonous weed to be rooted out: as is well known, two of the poets in the book—Ashraf Fayadh, in Saudi Arabia, and Dareen Tatour, in Israel—are currently in jail on charges relating to their work. Both are currently awaiting court decisions, and I was very glad that the crowdfunding enabled the anthology to make donations of £240 each to their legal funds.

Viene: How did you choose the poems included in the book?

Foyle: About half were solicited or commissioned, and the rest arrived in my inbox as a response to a call for submissions, which were translated into Arabic by Rewa’ Attieh and circulated via various blogs, including Arabic Literature (in English) and BWISP. The call was heard around the world—as well as from the UK and Palestine, I received work from Saudi Arabia, Dubai, America, and Australia. Most of this work was by men, and though I was thrilled to be sent work by major voices like Marwan Makhoul and, unexpectedly, new translations of Darwish, being determined to achieve a gender balance in the book, I actively sought out women poets. I found Fatena Al Ghorra on the website of the Poetry Translation Centre. The ground-breaking Scottish-Palestinian anthology A Bird Is Not a Stone (Freight Books, 2015) was another inspiring resource. Through the book’s editor, Sarah Irving, I invited Maya Abu Al-Hayyat to submit new work.

I also drew on my anti-Zionist and Palestinian friendship and cultural networks. Fellow cultural boycott activists Haim Bresheeth and Yosefa Loshitsky brought Dareen Tatour’s plight to my attention and connected me with her friend and supporter Yoav Haifawi, who is allowed to visit her during her house arrest. And thanks to my work for the Al Ma’mal Foundation in Jerusalem, co-translating the collection Wounds of the Cloud by Yasser Khanger of the Occupied Golan, I was in communication with American poet and translator Marilyn Hacker, who recommended Deema K. Shehabi, with whom Marilyn had previously collaborated. Maya, meanwhile, put me in touch with Fady Joudah, and I received permission to publish some of Ashraf Fayadh’s new poems from one of his previous translators, Mona Kareem, whom I found on Facebook, as I recall.

In the case of the anthology, I wanted to showcase poems that present the Palestinian narrative, in all its terrible complexity, straight from the heart.

Viene: What were the challenges you had to face, whether they be finding a publisher or translating from Arabic or disagreements between you and the authors?

Foyle: The fundamental challenge, of course, was the fact that I don’t speak Arabic. Looking back, if I could do one thing differently it would be to appoint an Arabic-speaking editor right from the start. The main reason I didn’t do this was because I didn’t have the funding to pay such a person the sum they deserved. I wasn’t being paid myself—the research grant covered only my expenses—which I didn’t mind, but I didn’t feel it was fair to approach someone I didn’t know and ask them to do an enormous amount of work for free, or a pittance.

Whether through naïveté or foolish pride, I initially didn’t see this lack as an insurmountable problem. I was imagining that I would publish English translations of Arabic poems that had previously appeared in print and would not need further editing. But as I began receiving submissions from diasporic poets, my vision for the anthology changed: I realized that in order to truly reflect the global nature of Palestinian poetry, I needed to include work originally composed in English, regardless of whether or not the exilic poets also wrote in Arabic. Although painfully aware that I would be unable to assess this new work, I decided to commission translations into Arabic.

Fortunately, all the contributors shared my ambition and, with infinite grace, did everything they could to help me achieve it. Fady Joudah generously translated his own poems for the anthology, while, thanks to the crowdfunding, I was able to pay a token extra fee to the small core team of Mustafa Abu Sneineh, Waleed Al Bazoon, Josh Calvo, and Raphael Cohen, who together ensured that all the Arabic texts were professionally edited and proofread.

Even with all hands on deck, though, this was no easy task. In fact, thanks to a perfect storm of Eurocentric software problems, it felt at times like bailing out a sinking ship. As I started to compile the master document from all the submissions, I discovered that I couldn’t cut and paste the Arabic texts in Microsoft Word without the text and/or the punctuation flipping into mirror-image. “Flippin’ Word,” I called it, though it wasn’t funny, the errors taking hours to correct with the cross-time-zone help of the translators and their Arabic-enabled software.

And worse nightmares were to come: having finally got the Word document afloat, I was aghast to realize that the resultant Arabic PDF was not only terribly fuzzy but largely illegible—many of the texts had disintegrated into isolated lettering. Apart from spending £1000 we didn’t have on new software that the Smokestack designer didn’t know how to use, there didn’t seem to be a way to fix that problem: two days before the printing deadline the designer confirmed that the only way he could create a viable Arabic PDF was by inserting screenshots from the Word document—a process that would result in unprintable low-res images.

Faced with the unthinkable prospect of having to abandon the Arabic texts, I went into a kind of state of shock. I didn’t have time to break down, though. Thanks to the crowdfunding, able to afford to hire someone to do an emergency job, I issued a plea for help on Facebook. “Don’t worry,” a Saudi friend reassured me over email, “Allah will make it easy for you,” and she was right. Within half an hour the book’s savior had arrived; and fittingly, she was a Palestinian. Although not a professional designer, Merna Azzeh in Ramallah, the daughter of an Arabic teacher and a self-described pedant, did a superlative job on the book. She and I worked round the clock perfecting the Word document, Merna catching outstanding errors and tweaking translations, while I, standardizing line spacings and page numbers, at last learned how to read Arabic, noticing a translator’s credit that had been accidentally cut and pasted into a poem. Finally, we were done, and Merna’s Arabic software created the beautiful, crisp final PDF in a matter of moments.

But though it was a practically vertical learning curve, editing the anthology has been an amazing, humbling experience. I feel I have made friends for life, bonded by our powerful twin commitment to poetry and justice for Palestine.

There’s a great thirst now to hear the Palestinian side of the story: the last ten years have seen an international flowering of Palestinian writers and filmmakers and artists.

Viene: Was there any poet or poem that you would have liked to include but couldn’t? And why?

Foyle: Palestinian poetry is an extremely rich field, and there are so many poets I would have been honored to include: Mourid Barghouti, Tamim al-Barghouti, Zakaria Mohammad, Nathalie Handal, Suheir Hammad, Rafeef Ziadah, and Remi Kanazi all spring to mind. But I also wanted to discover poets, and so I am consoled by the fact that, in not approaching everyone on my wish list, I created room for brilliant young writers like Sara Saleh and Mustafa Abu Sneineh.

Still, it was very hard to draw the line: I took two more poets than I’d originally intended, and my hope is that a larger English-language publisher will see the potential for a doorstopper anthology of Palestinian poetry in translation. I will just add that I did want to include new work by Yasser Khanger, as a show of solidarity, but although Golanese Syrians suffer parallel oppression from the Israeli Occupation, Andy felt the book should be limited to Palestinian poets, which I think, in the end, is a fair stipulation for the publisher to make.

Viene: How did you meet Mustafa and Fareed?

Foyle: Mustafa Abu Sneineh emailed me early on, and, as he lives in London, when I accepted his work it made sense to meet him to go through his translations together. We met up first at the South Bank Centre, where Mustafa was nearly ejected by the security guard for bringing his bicycle into the café, and later on, as the family feeling of the translation team grew, at Mustafa’s flat with his partner and baby son, who was so utterly captivating that I decided the book should be dedicated to him and the other contributors’ children and grandchildren.

I met Farid Bitar briefly in Egypt in December 2009, where we were both participating in the Gaza Freedom March in Cairo, an international demonstration to mark the first anniversary of Operation Cast Lead. Farid and I had become Facebook friends, but we didn’t properly communicate until he submitted some of his work for the book and sent me his CDs, which I loved. I was absolutely thrilled that Farid made it over to London for the launch, where he read with Mustafa, me, and two of the translators, Katharine Halls and Waleed Al-Bazoon and spoke movingly of his experiences as a poet-in-exile.

Viene: What was the reception of the book like?

Foyle: The reception so far has been incredibly encouraging. The crowdfunding raised £1100 from generous donors in seven different countries. Between the crowdfunding reward copies and bookshop preorders, the book sold 250 copies before it was even published. The University of Chichester sent out a press release to the national media and promoted the book with a banner story on their website. And the London launch, at P21 Gallery, attracted sixty people, a sell-out crowd of whom only a handful were my friends! Most wonderfully of all, the Educational Bookshop in Jerusalem has ordered copies. For at least one of my poets, that is a dream come true.

Viene: What’s poetry for you?

Foyle: To me, personally, writing poetry is a lifeline, and the poetry I love the best has a sense of absolute necessity about it.

Viene: How do you think a poem, or writing in general, can change the world?

Foyle: I would never argue that literature alone can change the world. I firmly believe that artists need to recognize their responsibilities as citizens and develop an activist mind-set in order to achieve structural change in the world. But I do believe that culture has a profound role to play in altering mind-sets, especially those that underlie entrenched conflicts. By representing complex human responses to conflict, fiction and poetry challenge stereotypes and influence people’s perceptions, not just of others but also of history.

Through its rootedness in the sensual world, literature also generates a sense of shared experience, and as a vehicle for dreams, it can create inspiring images of a better common future. Literature is also a place where marginalized voices can build influence—so often still, women and people of color have to fight to be heard in the public sphere, but in poetry and fiction their voices sing in their concentrated essence. In the case of the anthology, I wanted to showcase poems that present the Palestinian narrative, in all its terrible complexity, straight from the heart. I hope the book will reach people who don’t know the story of the Nakba and reveal to them the remarkable spirit of a people who, with passion, humor, and aching tenderness, continue to resist nigh on seventy years of ethnic cleansing, apartheid, and military occupation.

I’m not the first to note that the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is a battle of narratives, and in that battle I do believe that the tide is turning. Due in large part to media coverage of Israeli atrocities in Gaza, more and more people all over the world, and especially younger people, do not accept Israeli aggression or Israeli impunity. There’s a great thirst now to hear the Palestinian side of the story: the last ten years have seen an international flowering of Palestinian writers and filmmakers and artists. The story they are telling is a grievous one, of course, but thanks in large part to the Boycott Divestment and Sanctions movement, people who wish to help change it can channel their anger constructively. As it did for black South Africans, from this global grassroots movement and its cultural expressions, justice for Palestine must surely follow.

November 2017