Poetry as “The Beginning of Difficulty”: A Conversation with Marcelo Rioseco

When I sat down with Chilean poet Marcelo Rioseco recently, we discussed topics of translation, poetry, influences, and living both inside and outside the US. After completing the English interview, we sat down for another conversation in Spanish, which is featured in the following video. A selection of Marcelo’s poetry, including “Hoy he despertado en español,” which I translated as “Today I Woke Up in Spanish,” is also included below.

Grady Wray: WLT has chosen to highlight your poem “Today I Woke Up in Spanish.” This poem refers to translation in a broad sense, not only translation of words but emotions (anxiety, inferiority). The last three lines suggest that in translation one is not oneself. You write, “I haven’t been able to translate / because translating is no longer being yourself, / but someone else, who translates and talks.” Describe what translation means in this poem and to you in a broader sense.

Marcelo Rioseco: In this book translation is understood as the act of translating oneself into another language. That is, thinking in another language, feeling in another language, existing in another language, almost as if one were a verbal object made of words and not of flesh and blood or marrow and nerves. In this sense you’d have to think that whoever translates himself ends up being “something translated.” The impossibility of translating is, of course, a way of saying that one is trapped in one’s own language, and, consequently, in one’s own world. And at the same time this poem addresses the intensity of existing in a language, a situation that can only be understood when you have to deal with a world where two or more languages are spoken. The poem you cite, in some way, speaks to this, but also it speaks to the failure of that translation; it’s like an ontological betrayal: We can’t be anything but what we are. Although I suspect that Fernando Pessoa would disagree with that affirmation.

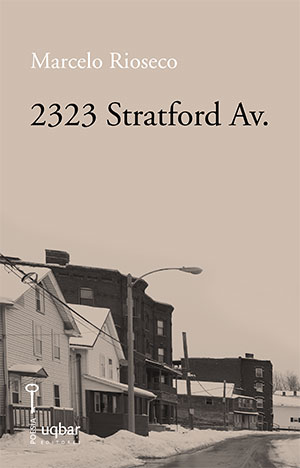

GW: “Today I Woke Up in Spanish” appears in 2323 Stratford Ave., a larger collection of sixty-eight poems in which you examine other issues apart from translating yourself into the United States. The poem from which you get the title of the collection, “2323 Stratford Ave.,” mentions a blank page, snow, the beginning of winter, and the final line states, “It’s me and this country.” Was this poem the impetus for the rest of the collection? Was it the first poem you wrote in the collection/in the United States? How does it serve to unify the rest of the collection?

MR: That poem is, of course, the center of the book. Nonetheless, something in its tone, in its cadence, is distinct from the rest of the collection of poems that make up 2323 Stratford Ave. Perhaps that’s what turns this poem into a special creation. The original idea of the book sprung from a very specific situation. In the winter of 2004 I was living in Cincinnati, in an apartment that was on the third floor near campus. It was a sort of attic with slanted ceilings and very small windows. It felt slightly like a cave or a cage. One weekend in January it started to snow. I hardly knew anybody in that city, and I’d been living in the United States for no more than six months. It was a very difficult situation, and for a moment I had the image that the only thing that was happening to me in this new country was that I was contemplating how the snow was falling as I sat in a chair facing a window. I dare say that it was, in some sense, an almost religious experience. It was me, there, in an absurd room, alone, in my apartment, and outside was the United States, and that same United States was written in English. And from that experience comes the line you cite: “It’s me and this country.” Right then I began to write and, of course, the snow seemed like a blank page as if I were writing on it. But that came afterward when I realized that the book was playing with the idea of what’s inside vs. what’s outside. Going out into the world, going out on the street that existed for me in another language was also coming out of myself, of my experience, to put it into words, to write this book. On the other hand, I have to tell you that “2323 Stratford Ave.” was not the first poem in the book. I had the mental image of someone trapped in an attic who sooner or later would have to come out of that place and confront the reality of the street. Nonetheless, the image of someone contemplating the snow came later, paradoxically. It appeared when I had several other poems written and I started to realize where the book was going. Probably the first poem that I wrote is “Make an Appointment with Yourself,” which is the first poem that appears in the published collection.

MR: That poem is, of course, the center of the book. Nonetheless, something in its tone, in its cadence, is distinct from the rest of the collection of poems that make up 2323 Stratford Ave. Perhaps that’s what turns this poem into a special creation. The original idea of the book sprung from a very specific situation. In the winter of 2004 I was living in Cincinnati, in an apartment that was on the third floor near campus. It was a sort of attic with slanted ceilings and very small windows. It felt slightly like a cave or a cage. One weekend in January it started to snow. I hardly knew anybody in that city, and I’d been living in the United States for no more than six months. It was a very difficult situation, and for a moment I had the image that the only thing that was happening to me in this new country was that I was contemplating how the snow was falling as I sat in a chair facing a window. I dare say that it was, in some sense, an almost religious experience. It was me, there, in an absurd room, alone, in my apartment, and outside was the United States, and that same United States was written in English. And from that experience comes the line you cite: “It’s me and this country.” Right then I began to write and, of course, the snow seemed like a blank page as if I were writing on it. But that came afterward when I realized that the book was playing with the idea of what’s inside vs. what’s outside. Going out into the world, going out on the street that existed for me in another language was also coming out of myself, of my experience, to put it into words, to write this book. On the other hand, I have to tell you that “2323 Stratford Ave.” was not the first poem in the book. I had the mental image of someone trapped in an attic who sooner or later would have to come out of that place and confront the reality of the street. Nonetheless, the image of someone contemplating the snow came later, paradoxically. It appeared when I had several other poems written and I started to realize where the book was going. Probably the first poem that I wrote is “Make an Appointment with Yourself,” which is the first poem that appears in the published collection.

GW: One of the strongest themes of the collection scrutinizes life in the United States, thus the title 2323 Stratford Ave., your first street address in the United States. Other poems such as “Going Out in the Elements,” “I’m not Chilean,” “Sooner Mall,” “Today a Woman I Didn’t Know,” “The Southern United States,” “Possibly They’ll Say I’m Pedro,” and “Pedro Pérez Spanish Instructor” conjure up images that few people who are from the United States recognize. How do these poems reflect how a foreigner feels and sees the United States?

MR: If I had to say something about the group of poems you mention, it would be that all of them are poems that work with feeling strange, perplexed, or like “the other,” what we call “extrañeza” in Spanish: the strange feeling of being in a strange place, but also that of feeling strange or odd with yourself. I imagine that people in the United States would never be able to recognize their country in these poems; the feeling of strangeness that’s there is mixed with an experience that for me is strictly “American”: the experience of emptiness or a vacuum. Solitude in the United States is the experience of being alone in an immense empty space. I would venture to say that in Latin America it is different. You come closer to being alone in Latin America, but you’re surrounded by people. It’s solitude, I should say, in its purest state. By this I don’t mean to say that it’s better or worse, but that it’s different and, perhaps, unique. For me, the United States is a country that you can’t imagine unless you live in it for many years. There’s something unique, so “American,” so different that it’s very difficult to compare America with any other country in the world. The United States challenges the very idea of what we understand by the “Western world.” That idea is, to me, the origin of its strength, that sensation of being in an isolated but young society, that always looks toward the future and what’s new. From there, probably, comes its emptiness and also its madness. Perhaps my opinion is influenced by its great distances, by the very enormity of the country, by the sensation that there are hundreds and hundreds of miles where there is nothing. But let me insist, I don’t judge this characteristic. I bring it up simply as one witness of the immense “labyrinth of solitude” that is the United States.

GW: You also cover several other themes in the collection such as solitude, God, memories, the act of writing poetry, anguish, pain, and suffering. However, you do not lose your sense of humor or play. How does humor or play function in 2323 Stratford Ave.?

MR: Humor is vital. It’s a form of survival. Humor tells you you’re not that important, that you can’t take yourself so seriously. So, the speaker in 2323 Stratford Ave. looks at himself with a certain lack of confidence and, many times, with a certain tenderness. For example, the relationship with God is not combative, it’s like a child who knows he still isn’t as old as his father and so, therefore, he’s denied certain things. Now that I’m answering this question I’m realizing that there’s a relationship between tenderness and humor in the book. Perhaps it’s what gives an intimate tone to the poems that you don’t find in my other books. Another way of understanding humor is as a form of finding another dimension for the experience of grief or pain. And even though this experience can take you to an extreme limit, it never gets to the final limit. Humor comes back to tell us that all our pain, grief, anguish, and suffering is the same experience as any other human being’s. In that sense, 2323, in spite of its themes, defends a lesser voice, a subdued one, the voice of a common person who is capable of smiling with irony when facing his or her own abyss.

GW: I assume that another aspect of play in 2323 Stratford Ave. is intertextuality, or at least interreferentiality. I note echoes of other Latin American poets, like César Vallejo and Fernando Pessoa. How did these poets influence you, and who are others who echo in this collection?

MR: I’ve read Fernando Pessoa all my life. He’s a poet who’s been very close to me, much more important than Neruda, to cite a known example. For me, the existence of the heteronyms of Pessoa was decisive in my literary life. It gave me the chance to understand that unity wasn’t that important, that starting from Pessoa’s tremendous fragmentation, it was possible to construct a literary work. In some way it represented the end of the Romantic idea of the universe as a lost unity. In that sense, 2323 Stratford Ave. would be closer to Alberto Caeiro than to a poet like Álvaro de Campos, but definitely much closer to Bernardo Soares, the author of The Book of Disquiet. Caeiro is a serene poet, but the speaker in 2323 isn’t. The voice of the speaker in 2323 is nervous, apprehensive, and somewhat paranoid at times. For that same reason it’s not unusual that the César Vallejo of Human Poems is present in my book; there also is the experience of splitting oneself open that interests me a lot: that of seeing oneself organically, biologically, as if the corporeal were almost like another being. Seeing, examining one’s own bones, one’s skin, one’s marrow, it seems to me, is something that in some way is repeated in 2323.

GW: Finally, what would be the meaning of poetry for you?

MR: My answer to your question is deeply personal. Every poet, I suppose, defines poetry according to what she writes, to what she reads and, of course, to what she is. I, personally, continue to think poetry should reveal something, scrutinize reality, be a form of looking at and depicting what’s hidden. All the definitions, nevertheless, are tentative and, in some way, pedagogical. That’s the problem. At any rate, I’ll try for a personal response.

What, then, would poetry be? What would be its significance for me? Perhaps poetry would be, finally, an eternal arriving. It’s impossible to know if the destination of poetry is reaching a certain dawning state from where the secret would emerge in the form of something new. Certainly it would be a form of hope in which that unique moment of dawning were a moment of light, splendor, and even an indiscernible form of grace. Clearly, poetry, by being something made of words, translates that experience through the imperfect forms of language. It’s a mediated experience. Maybe, for that same reason, poetry always stays in that latent state, potential, like something that never finishes developing. In that sense, you have to understand that poetry, no matter how close it comes to the experience of grace, is not a form of mysticism; it remains and will remain distant from religions and dogmas. What it reveals—if it is perhaps able to reveal something—is only language. We could say that poetry would be behind the result of an experience of writing. And what’s commonly called a visionary state would be poetic, literary intuition, a glimpse, what one catches sight of beyond language. Something, certainly, unattainable or unrepresentable or something that one can’t put into words, which no poet really taps into. Therefore, I think the word “secret” defines almost exactly the center component of what here I’ve called dawning. Arriving at the dawning. Or, even better, being the dawning (or, the end of arriving) would be penetrating the secret. Nevertheless, ours is only to try to arrive, it would be an “eternal arriving,” delving into the secret, if you will. Just the same, poetry could also be seen as the beginning of difficulty.

November 2014

Three Poems by Marcelo Rioseco

Hoy he despertado en español

Hoy he despertado en español y me he puesto remoto,

hoy me he sentado en español y he escrito

para no olvidarme que despierto y me siento en español,

pero vivo en inglés. Esa es la única realidad que me obliga

llena de palabras duras, de verbos sajones e industriales,

de pronombres que me cierran el paso

y son grandes en número como mis recuerdos.

Hoy soy torpe, pero torpe en español. Todavía.

Y no sé hablar, no sé decir gracias sin pensar

que digo “bienvenido”, sin saber si esto es

lo que debe suceder o en qué idioma debe suceder.

Hoy soy en español, poco funcional, sudamericano,

un poco indio, un poco colonizado

como los cuatro rincones de mi país

que tiene fe en el vidrio y los números.

Hoy he despertado en español, mis extremidades

en español, mi nariz en español;

mis ojos, mi pelo, mi boca en español

y no he sabido traducir

porque traducir ya no es ser uno,

sino otro, que traduce y habla.

Today I Woke Up in Spanish

Today I woke up in Spanish and became distant.

Today I sat down in Spanish, and I wrote

not to forget that I wake up and I feel in Spanish,

but that I live in English. That’s the only reality that forces me,

full of tough words, Anglo-Saxon and industrial verbs,

pronouns that get in my way

and are large in number like my memories.

Today I’m awkward, but awkward in Spanish. Still.

And I don’t know how to talk,

I don’t know how to say “thank you” without thinking I say

“welcome,” without knowing if this is what should happen

or in what language it should happen.

Today I’m in Spanish, barely functional, South American,

somewhat Indian, somewhat colonized

like the four corners of my country

that has faith in glass beads and numbers.

Today I woke up in Spanish, my extremities

in Spanish, my nose in Spanish,

my eyes, my hair, my mouth in Spanish,

and I haven’t been able to translate

because translating is no longer being yourself,

but someone else, who translates and talks.

2323 Stratford Avenue

Despierto y me levanto,

me acerco a la ventana y miro,

afuera nieva y es temprano todavía.

Los autos cubiertos de nieve,

las calles vacías y una luz brillante

y metálica como si saliera proyectada

desde el suelo. Miro a mi alrededor

un departamento pequeño, pero barato,

muebles de segunda mano, libros

en el suelo y sobre una mesa desordenada

un café hirviendo y una página en blanco.

Creo que me gustaría escribir un poema

sólo para decir que está nevando.

Trato entonces de pensar en Chile

y no se me ocurre nada

porque no hay nada en qué pensar

afuera está nevando

eso es todo, en Chile no nieva

es simplemente nieve cubriendo las calles

en silencio, como una página en blanco

que nadie ha escrito aún, es Cincinnati,

el invierno que recién comienza,

yo y este país.

2323 Stratford Avenue

I wake up, and I get up.

I go to the window, and I look outside.

It’s snowing, and it’s still early.

Cars covered with snow,

empty streets and a shiny, metallic light

like it was projected

from the ground. I look around me,

a small apartment, but cheap;

secondhand furniture, books

on the floor and hot coffee on top of a messy table,

and a blank page.

I think I’d like to write a poem

only to say it’s snowing.

I try to think about Chile,

and nothing comes to mind

because there’s nothing to think about.

Outside it’s snowing,

that’s it; in Chile it doesn’t snow.

It’s simply snow covering the streets

in silence, like a blank page

no one has yet written, it’s Cincinnati,

winter’s just beginning.

It’s me and this country.

Apuntarse en una agenda

Conjugarse, buscarse un verbo

un tiempo verbal y tratar de aparecer,

de ser, aunque sea experimental, ilusorio

y estar allí, apuntándose en las agendas;

disfrazarse de cita y un día decir:

“Hola, ¿cómo estás?”, simplemente para saludar,

para ser. Todo con tal de estar junto a alguien

y respirar en grupo, porque uno se cansa

de tanto observar frases solas, vocales mudas,

la arrogancia de las consonantes, ¿quién sabe?

Apuntarse en una agenda, en las páginas de los libros

como una errata y aparecer de repente

como una mala noticia y obligar a los otros

a vivirlo a uno con todo ese defecto que se tiene, digo,

tan ostensible, tan costoso de solucionar.

O apuntarse como algún adverbio

para modificar, pienso, tanto adjetivo suelto

o verbo sin sustantivo que se anda trayendo.

Pura superficialidad y uno siempre tan mal conjugado

como la nieve que se ve caer y no se entiende.

Make an Appointment for Yourself

Conjugate yourself, look up your own verb,

your own verb tense, and try to show up,

to be, although it may be experimental, illusory,

and be there, putting yourself on planners;

disguised as an appointment and one day say:

“Hi, how are you?” just to say hi,

to be. Everything just to be with someone

and breathe together, because you get tired

of observing solitary phrases, silent vowels,

the arrogance of consonants, who knows?

Make an appointment for yourself, on the pages of books

like a typo and suddenly show up

like bad news and force others

to live with it, with all the defects it has, I mean,

so visible, so expensive to fix.

Or make an appointment as an adverb

to modify, I think, so many loose adjectives

or so many verbs without nouns that are always hanging around.

Pure superficiality and always so poorly conjugated,

like the snow you see fall without understanding.

Translations from the Spanish

By Grady C. Wray

Marcelo Rioseco is a Chilean writer and has published several books of poetry, fiction, and nonfiction. 2323 Stratford Ave., his latest book of poetry, was published in Santiago, Chile, in 2012. His poems have appeared in various Spanish-speaking countries, including Chile, Argentina, Nicaragua, the Dominican Republic, Spain, and Venezuela.