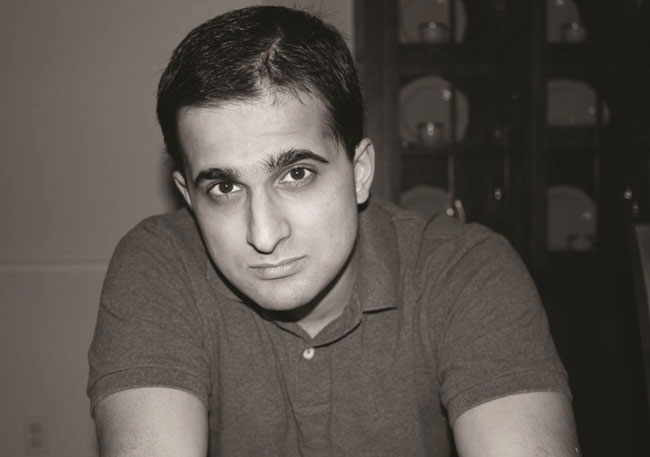

Poet, Radiologist, and 007 Wannabe: A Conversation with Amit Majmudar, Ohio’s First Poet Laureate

A diagnostic nuclear radiologist, Amit Majmudar was named the first poet laureate of Ohio (2015–2017). He has published three books of poetry, including 0˚, 0˚ (2009), which was a finalist for the Poetry Society of America’s Norma Faber First Book Award, and Heaven and Earth (2011), which won a Donald Justice Prize, and most recently Dothead (2016). He is also the author of two novels: Partition (2011) and Abundance (2013). Majmudar’s work has appeared in the New Yorker, the Atlantic, Poetry, Kenyon Review, and the New York Times. The following conversation, part of an ongoing dialogue, occurred via email and Skype during June and July.

Renee H. Shea: How do you feel about being the first poet laureate of Ohio? Do you feel pressure to define a role or initiate a tradition?

Amit Majmudar: It’s definitely an honor to be the laureate, and to be the first. I don’t feel much in the way of pressure—there is a lot of latitude regarding what I can do, and the stipulations are rather light; I met my annual “quota” of public appearances during National Poetry Month alone. I want to set a tradition in a general sense—one that involves initiatives and projects, and a regular practice of involving other poets and artists rather than just being a “poetry ambassador” who goes around promoting my own work. But I would like to keep that open, unstructured aspect intact for future poets who hold this post.

RHS: You have a day job! In fact, it’s an impressive career on its own. How have your colleagues responded to your being named Ohio’s poet laureate?

AM: None of them read poetry regularly, but I think that, like my own parents, they were thrilled to see me recognized for something so “out there” as poetry. It really is a different world to most people, but I’ve never thought of it as anything other than that. I can’t imagine what it must be like to be a “networked” poet who spends most of his or her time among other intellectual literary types. I feel like this stuff is so dear to me precisely because it is so secret and alien from my day-to-day.

RHS: Even before the laureateship, you had a publication record that would make any writer proud—including those far older than you. How have you managed to do your work as a radiologist and be a pretty prolific writer?

AM: I work diligently in executing my ideas, “without haste but without rest,” as Goethe once said. I think that the work ethic I developed as a medical student and resident, working thirty-six-plus hours at a stretch sometimes, has never left me and serves me well now, as a writer/dad/radiologist.

RHS: You’ve written two novels, both well received, in addition to your poetry. But since this appointment, it seems you’re concentrating more on poetry. Have you moved away from fiction?

AM: No, not at all. I still write a lot of fiction, far more fiction than poetry. I have several novels on my hard drive. I am just waiting to produce a breakthrough manuscript. If you publish a lot of well-received novels that don’t sell well, you become a toxic asset to your publisher. For all my positive reviews, my sales figures in fiction have me running that risk at this point. So the next novel is going to have a chance (there are no certainties in this thing) of breaking through.

RHS: This is a two-part question, but it’s all about money. You’ve likened your job as a radiologist to a sort of patronage—your Medicis! That is, the fact that you have a successful career that pays your family’s bills frees you from restrictions to publish what “sells.” Do you believe that our twenty-first-century society places little value on poetry?

AM: When it comes to page poetry, I reject the usual association of “eyeballs” and the worth that holds for movies, television shows, popular fiction, Broadway musicals, and so on. Indeed, the terms “value” and “worth” themselves have a poisonous (to me) economic connotation and origin. I have pursued worldly wealth through what I believe are noble means—a job that would not force me to make any moral compromises. Among the more lucrative professions, medicine has that going for it in a way that finance and law do not.

As for the laureateship, I don’t think anyone expects a significant stipend. Poets write poetry because they enjoy it, and I am no exception, and the state has no obligation to fund monetarily a post that “pays” in prestige and exposure. The amount of exposure you get as laureate is not something you can purchase on the free market, actually. I mean, I got on CNN as a result of this. It’s crazy.

RHS: How can I resist asking if you’ve seen Hamilton—and if it surprises you to see the extraordinarily enthusiastic response to a play that combines rap, hip-hop, and various poetic forms to interpret the Founding Fathers.

AM: Doesn’t surprise me—part of my pitch to be laureate exalted the public appeal of hybridizing other, more attractive art forms to poetry. The problem, of course, is that the burden of power-generation can be off-shifted onto the other art forms and performers. If you read the libretto to Hamilton, it’s no great shakes as verse, or as a poem per se: as Lin-Manuel Miranda himself has pointed out, his kind of writing mostly takes life in performance. Your language does not have to do the heavy lifting if you have a $12 million budget and the most talented musicians, actors, and dancers in New York presenting your words. What we do as “page poets” has a smaller audience because it has a $0 budget, involves language married to no other art form, and strives to create a word sequence with all the music and dance and emotion baked into it.

RHS: You seem to have a strong attachment to your Indian cultural heritage. How has that influenced your writing, particularly your poetry?

AM: I think I write a great deal about it. But it’s an identity not so much Indian as it is Hindu. These are different things, of course. Contemporary Indian culture is a sort of hybrid colonial outpost of American pop culture. I get quite enough of the real thing over here, thank you very much.

I think inevitably the literary culture tends to expect people with foreign names or Asian or African ethnicity to write about the immigrant experience. Whatever you write about gets fed into that experience.

RHS: You’ve written about involuntarily being identified as an immigrant writer. Once that happened, how did it affect your writing style or subject matter?

AM: I think inevitably the literary culture tends to expect people with foreign names or Asian or African ethnicity to write about the immigrant experience. Whatever you write about gets fed into that experience. Having said that, I account for it, knowing that a significant number of readers, reviewers, and editors will be thinking in those terms—that narrative in their heads. The book Dothead is about a large number of different topics—from neuroscience to James Bond to Adam and Eve in the Garden. But I made sure to put poems that deal with ethnoracial and religious aspects and politics in the front of the book so that when a reviewer or editor saw the manuscript they’d associate it with the immigrant narrative that they talk about in politics and newspapers. There are a lot of other factors, of course, but it worked: Dothead has gotten more attention than anything else that I’ve written.

RHS: Identity’s always a tricky landscape, and yours seems to have expanding horizons. So if I asked you how you define yourself —doctor? writer?—what would you say? How has the appointment as poet laureate affected your response to that question? And which came first—science or poetry?

AM: I was attracted to writing first. Probably the only reason I actually ended up a doctor is because everyone in my immediate family is a doctor. If they had been writers or historians or lawyers or whatnot, my destiny may have ended up quite different. But I am quite at ease with how things worked out. I would say, though, that I don’t regard “doctor” as an accurate label of my identity. It’s what I do, not what I am. If a poet waited tables to make ends meet, we wouldn’t call him a “waiter-poet” and wonder how the waiting of tables informs his penchant for the sonnet. In my two years of college (I was a part-time student the whole second year), admittedly, all I did were sciences, and I ventured into some nonscience classes reluctantly, under duress from my advisor, and dropped them quickly. I had a clear professional goal in mind. I have always regarded formal education as vocational training. I knew even then that my real and meaningful education would take place alone, in the library, with books of my own choosing, away from professors and term papers.

RHS: There’s a lot of talk these days of tearing down the silo approach of academe where “disciplines” set rigid boundaries. The emphasis on STEM, some argue, should be recast as STEAM in order to add the arts. Where do you fall in this discussion?

AM: I don’t think adding art to a curriculum is really going to add much. I feel like I’ve known too many hard science people to believe in the teachability of the love of poetry or other fine arts. Perhaps because I do not believe in the teachability of love, period. Over the course of my medical training, I’ve come across people who have the love and people who don’t. Frequently the ones who don’t are the ones who do the best at the science stuff. There’s no telling who will have a tendency in this direction.

Having said that, techies and radiologists and hard-science STEM types all do experience “art” in their own ways. Television shows, animation, comic books, movies, pop music—these are all arts, after all. It’s just not art that was popular five hundred years ago in England. Someday in the far future, professors of literature will lament that astrophysicists aren’t studying or appreciating classical American rap texts. And the astrophysicists will shrug their shoulders, adjust their spectacles, and shoot for Alpha Centauri.

RHS: Dothead is your third book of poetry. How would you describe your growth as a poet?

AM: Weedlike. Some Ohio weeds: mile-a-minute weed, puerperal loosestrife, shattercane.

RHS: The title poem, “Dothead,” deals with serious subject matter, yet you wrote it in such a conversational style. Why did you make that choice?

AM: I think “TSA” is another poem where that pertains; it has a kind of sing-song meter often used in comic poetry. But the subject is serious. “Dothead” is written in the heroic couplet. I think what that does is to set up dissonance between the ear and the mind. It’s kind of salty sweet . . . salted caramel. That sort of confusion and dissonance, just as it pleases the tongue, poetically has a sort of pleasing effect between the expectation and experience of the reader. “Dothead” had to be this juxtaposition of daily conversational life and interaction in high school with the mythological image of a god dancing fire and destruction. It’s about setting up those contrasts.

RHS: You’ve talked about your fascination with James Bond—Fleming’s novels, your own attempts to write spy novels. So, does “James Bond Suite” (in Dothead) pay tribute? It’s delightfully playful . . . but maybe also a meditation on age and decidedly un-007 choices. Is it a farewell to your “Bondness”?

AM: Ah, for me to say farewell to my Bondness would imply I had some Bondness to begin with. I’ve always been more of a Q section nerd, not a lady-killing double-0 field agent. I don’t remember the circumstances under which I wrote the “Suite,” but in it, I do mention my age as thirty, so my twin boys were two at that point—not the best circumstances to imagine oneself a globetrotting man of mystery . . .

RHS: One reviewer described you as not an experimental, not a postmodernist, but “a social poet, a poet of the people,” yet you describe yourself as liking “obscure and hermetic poetry” without popular appeal. So is this paradoxical—that you write poetry with a popular appeal, though that’s not the poetry you like?

AM: I question whether my poetry has popular appeal, really. Based on my sales figures and lack of national book awards or fellowships or the like, I suspect I myself am obscure and hermetic. It is always interesting to me to see how some readers think my poetry is atypically clear relative to that of my contemporaries—while others find it quite impenetrable. It's all about what people’s set-point is as regards intelligibility.

RHS: Many of your poems are concerned about war—various dimensions of it. Dothead includes “TSA,” “Ode to a Drone,” “Killshot,” “The Start-Spangled Turban.” Do you think that your poems, or war poetry in general, helps us to make sense of the experience?

AM: War poetry is actually a “genre” of poetry with strict conventions that have changed over time. Since World War I, the only real acceptable attitudes toward war are “pity of war” poems or satirical poems against authorities. Homer alone is full-spectrum. You notice he includes warriors taking pleasure in killing. That is mostly unthinkable/unwriteable/obscene in post–World War I American war poetry, which focuses on orphans and dead innocents and PTSD and all that, though pleasure in killing is still a part of the war experience for soldiers and Marines. You can find clips on YouTube that are point-of-voice helmet-cams of guys taking out Afghan insurgents, and when they score a hit, they rejoice. They sound exactly like their team just scored a touchdown. You don’t hear that war cry of joy and triumph in American “war poems.” Nor the hatred of the savage other. Nor the grudging respect for the slain enemy. Nor even contempt for frivolous civilians after the return. Our war poems (mine included) are narrow-spectrum. I am going to change that shortly, though it would be rather difficult to get such poems published. Kipling (of the “Barrack-Room Ballads”) was the last to do it, and he is misread as a jingoist instead of what he is, which is a realist about points of view that are today discredited or frowned upon.

RHS: The poem “Language Barrier” in WLT and an earlier one, “Patient Histories” (both plays on words in their titles), interrogate how we talk about illness—or about the language used in conversations between patient and physician. These are such open-ended poems, so I wonder if you’re still asking questions, exploring yourself how language defines the patient/physician relationship. Or am I way off base here?

AM: Not way off base, no—but I would point out that there are relatively few poems about doctoring or the patient-physician relationship in my output. I generally stay away from that topic. I write to escape it, in fact.

RHS: The poem “To Anne Sexton” intrigues me. Do you feel a particular connection to her?

AM: A lot of people like that poem. I’ve gotten letters about it. I wish all the journals that rejected it could know that! I had a devil of a time getting a journal to publish that one. As for Sexton, I can’t say I read her all that regularly. I read her poems when I was twenty-one, and then she just popped into my head fifteen years later. I never know what triggers these poems. I recall liking her focus on myths and fairy tales, and how she didn’t stick to the usual confessional-poet script toward her later career.

RHS: “It’s fun to have fun / But you have to know how” is the epigraph to Dothead. So how did you learn how—or who taught you to know how? I’m betting it wasn’t Dr. Seuss . . .

AM: The whole library, to be honest. I’ve been reading everything I could get my hands on since I was eleven or twelve.

June–July 2016