More Than One Life: A Conversation with Lyn Coffin

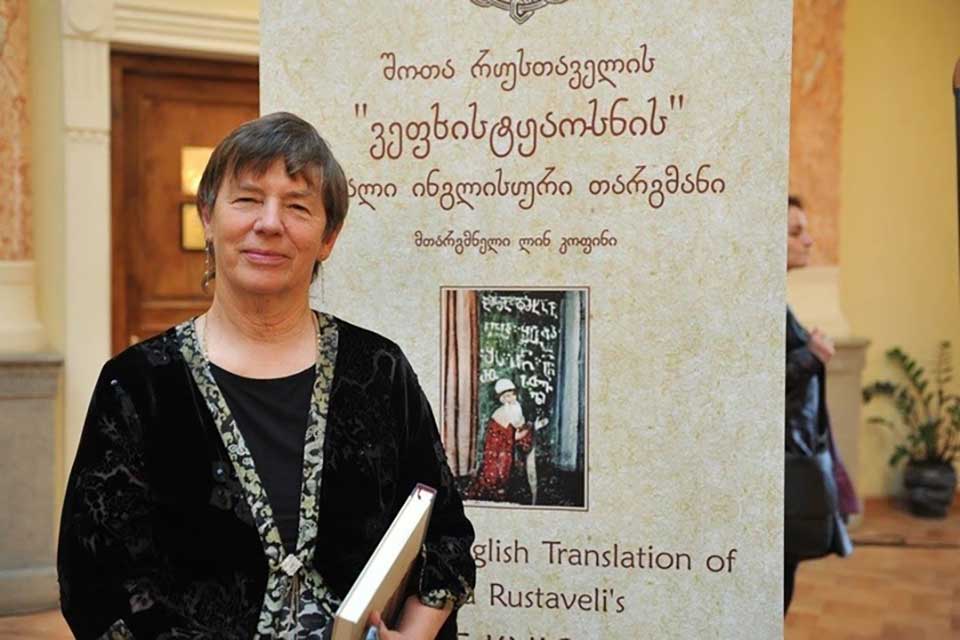

Described by Iron Twine Press as “the most accomplished writer most Americans have never heard of,” Lyn Coffin (b. 1943) is a prolific contemporary US poet, writer, and literary translator. Her impressive career spans more than five decades, during which she’s published over thirty books of poetry, fiction, drama, nonfiction, and translation. One of her most notable achievements is her translation of The Knight in the Panther Skin—a twelfth-century epic poem by Shota Rustaveli and classic of Georgian literature—into metrical and rhymed English verse. Additionally, she has received several awards such as the First Prize in Translation from the Academy of American Poets for Jiří Orten’s Elegies (1975), the Gandhi Poetry Prize from the World Congress of Poets in India (2007), and the Georgian National Literature Prize SABA (2016).

In the following interview, Coffin shares her thoughts about poetry translation, authorship, identity, and literary creation.

Alaaeldin Mahmoud: You have been described as a prolific and versatile writer who has attempted various forms and genres. Which writing form do you identify with the most or feel most comfortable with?

Lyn Coffin: I don’t know if I have a favorite literary or poetic form. That’s like asking who your favorite child is. I like working in forms in general, and when I am able to complete or manage a really complicated form, like a villanelle or sestina, that makes me very happy.

Mahmoud: Your poetry—published over the past four decades—shows a persistent and relentless commitment to poetic form. Why?

Coffin: I don’t think I have a commitment to form, as I also like writing “free verse.” But sometimes focusing on the form and its constraints provides a kind of freedom from what I might call the “threatening liberty of fondness.”

That is an interesting way of phrasing it. I like form because it seems to me that the form and the subject matter exist in an energetic, diametrical relationship to each other.

Mahmoud: If your literary work were to be anthologized, where would it most likely be published? In other words, how would you like your work to be defined?

Coffin: I’m not sure if I like any work to be defined at all. I might appreciate its being appreciated in different forms—as one appreciates a beautiful woman in different outfits.

I’m not a good person to ask where my work should appear. I don’t write poems designed to “fit” a particular publication. To me, that would be like giving birth to a child you “designed” to go to a certain college.

I don’t write poems designed to “fit” a particular publication. To me, that would be like giving birth to a child you “designed” to go to a certain college.

Mahmoud: Your X handle reads, “‘Coffin may be the most accomplished writer most Americans have never heard of.’ – Iron Twine Press.” Which of your works do you think are included in that?

Coffin: The wire from Iron Twine was written by Ethan Yarborough, somebody who used to be—and maybe still is—the main editor at Iron Twine Press. He was a student of mine at one time. He’s an admirer of much of my work. To know why, you’d have to ask him.

Mahmoud: To what extent do you define yourself (or not) as an “American” writer? In other words, as an author and translator, do you think your Americanness shows in any way in your literary work, including your translation?

Coffin: I am probably the last person to identify the extent of my Americanness. Maybe it’s sort of like asking to what extent is my writing “feminine.” I don’t know. I sometimes have trouble answering such questions! I would assume that my Americanness and my feminineness show in everything, even when I try to disguise it or represent something else.

Mahmoud: What motivated your decision to translate poetry, generally speaking? Is it your personal fascination with or preference for specific languages—such as Czech, Dutch, Georgian, Persian, or Spanish—or the peculiar experience of the individual poets?

Coffin: Who am I to say what brought me thirsty to the well? I don’t mean to be difficult. I love poetry and resound to its beat, and when I hear poetry in another tongue—when the woods of words come to me like Dunsinane shedding leaves and saying, “I mean something important, but you don’t understand it”—I feel driven to know at least something, to understand in part even as I am understood in part.

Who am I to say what brought me thirsty to the well?

I’m not sure this makes sense, but it sounds right. It’s all a mystery and inspiration, a chipped hand full of cold, clear water. I am affectionately trying to say what we pretty well know cannot be said, but it is a noble effort for that reason.

Great poetry is great poetry. Ever since the Tower of Babel, we’ve been separated from one another by language differences. Translating foreign languages is a love of my life and a death-defying adventure. It’s mind-expanding travel. It opens new worlds. Translations are also really mind-expanding (in some ways like a drug) and fun in the way crossword puzzles are fun. Translations open doors and swim oceans and climb mountains! Translating a poem is like opening a door, solving a puzzle, exploring terra incognita, going on a date, eating a meal from a foreign country, going to that foreign country, reading a new book by an author with whom you are unfamiliar. On days or weeks when the muse is in hiding, there is nothing better.

Imagine yourself at a bar (but not drinking), and you see a young, attractive woman across the room, and you can’t understand what she is saying (you’re too far away). But you catch her gestures, maybe the flash of her smile. You want more than anything to know her. What motivated you to fall in love? Was it her smile, her kindness, her background, the way she leaned in when you said, “I cherish wisdom”? Was it not all this and more, and do you really know enough to say, “It was this, it wasn’t that”?

It all began when a university professor (maybe Ladislav Matějka, professor at the University of Michigan) sent me some poems of Jiří Orten’s and some very rough, not very good translations—no, not even translations but translation attempts—of poems by Orten. I think “White Picture” was the first, and the English was very rough, but I could see through the poor English to this fabulous poem and this fabulous poet. I knew a little bit of Czech, and I wanted to transmit this fabulous poet to English. “A kind winter day / Someone stood in the snow / Palette in hand / Snow was falling / It fell on the artist’s palette / He paid no attention / He painted” (something like that). I feel I live with Orten, with this poem “White Picture,” with Czech poetry (I was married to a Czech), and I set out to learn Czech to translate this poem, this poet. There is no satisfactory explanation for why, any more than there is for falling in any kind of love. It happened before I knew it. I was over my head in snow in Orten’s “White Picture.”

It happened before I knew it. I was over my head in snow in Orten’s “White Picture.”

In other words, what motivated my decision to translate poetry was that I had learned a little Czech, I read Orten, and fell, as it were, in love with him. And I couldn’t stand the fact that here was a great poet who was unknown to the contemporary world of letters, so I wanted Orten to be known about, to be heard.

Mahmoud: To whom do you write? Who is your target audience?

Coffin: I write for anyone who will or might listen. I write to solidify old friendships and make new ones, to convert events, to relieve internal pressures, to interest, to convince, to intrigue, to introduce myself, to change someone’s mind, to make someone think again, to change people, to understand myself better, to try to contribute to the world (or at least the world of letters).

I write because I don’t know any better, to prove my critics wrong, to prove my friends correct in their high assessment of my abilities. I write because it lets off steam, because I can. Because people say they find my writing helpful, because people who do not find my writing helpful might find the latest writing more useful. Because otherwise what am I, and what am I doing?

Mahmoud: I am intrigued by your translation collaborations such as those you accomplished with the help of Zdenka Brodska, Gia Jokhadze, or Nato Alhazishvili, or even the authors themselves such as Germain Droogenbroodt and Mohsen Emadi.

Coffin: Each collaboration was different, and all are hard for me to remember. With Zdenka, she knew English well and was able to question words or phrases that seemed to her to strike the wrong note. I can’t remember any examples, alas, but she would read translations and question lines or phrases. “Does this sound negative in English?” she might ask, “because in Czech it is very insulting.”

Mahmoud: What are the books you regard as your best achievement? Why?

Coffin: I don’t know what my best or highest achievement in writing is. I think that’s for readers to decide. Maybe I should mention the formal poems I’ve done, though. I think some of my sestinas and villanelles are pretty successful in that readers can stop being aware of the difficulties of the form and concentrate on the music of the poem. As far as the book in which my best achievement resides, I think it would be The Aftermath. I think it’s a good novel, a suspenseful story, and it has poetry driven into a very “modern” and “urban” tale of crime.

Mahmoud: Do you agree with those people who put forth the idea that poetry is untranslatable?

Coffin: Yes, I think great poetry, maybe all poetry, is untranslatable. The meaning of something gets lost, but something gets found as well. What I mean is, I think a good translation can turn out to be as good as or—in some cases—even better than the original.

I think a good translation can turn out to be as good as or—in some cases—even better than the original.

Mahmoud: Do you think that literary translation (or literary translation collaborations) disrupts or discredits the idea of authorship?

Coffin: An author is an author when they write a poem. For example, this poem does or does not get translated. A translation attempts to reflect—as in a mirror—an original poem. I don’t see any kind of translation as discrediting authorship, although good translations may bring honor and credit to the author as well as to the translator.

Mahmoud: You decided to translate Georgia’s all-time national epic, Shota Rustaveli’s The Knight in the Panther Skin, into English. What sparked your interest?

Coffin: Someone told me about The Knight. I find the story of the mysterious Rustaveli fascinating, and the idea that someone long ago had written a novel in verse, and complicated, intricate, challenging verse at that! I was lucky enough to have friends who mentioned The Knight in the Panther Skin, and I read what I thought was a poet’s translation, which I won’t name. I thought it was pretty poor because the outrage in English was awkward and sometimes stilted. I got interested in the work behind the translation and read some commentary, and it also interested me.

I don’t know where I heard about The Knight first, but I was immediately intrigued. Here was a great work of world literature, and the English translations that I read didn’t (to my mind) really suggest why The Knight was considered a great work. So I spoke to a Georgian friend—Gia Jokhadze—about it, and he started going over the lines. I began to see what was great about it, enough so that I hoped I could get at least some of the greatness into a new translation.

Mahmoud: A good part of your work suggests some kind of interest, if not a more-than-usual preoccupation, with the (ex-)Soviet world. This is easily discernible in your numerous translations from (or by the help of) Georgian friends/collaborators, your play His Russian Wife (2010), and in the short story “Back from the USSR” (2011).

Coffin: I’ve always been fascinated by, and admiring of, Russian literature in translation. Sometimes I feel that my soul is more Russian than American, especially as I tend to respond with exaggerated emotions. I seem myself to share a Russian sensibility. On my school slate, emotion is written in large scrawly letters.

For my interest in Russian literature, I read much of Dostoevsky even before high school. I loved his tortured and sometimes torturous psychologizing, his intensely tormented characters. I was fascinated by the combination of—what seemed to me—very modern ideas (put forth proleptically) and old-fashioned narrative. I don’t think anyone but someone very blind could fail to see the appeal of Dostoevsky.