The Liturgy and Anxiety of Ordinary Lives: In Conversation with Rigoberto González

Recently, I scheduled a zoom call with my friends Bright Ikenna Uwandu and Anthony Chibueze Ukwuoma with the cryptic agenda of “catching up.” The meeting was just an excuse to escape from the seriousness of adulthood and spend some time talking about small things. Bright and I also intended to listen to Anthony rant about his frustrations with finding a relationship. I was prepared, as always, to announce to Anthony the sad news that entering a relationship might be the easiest step on his journey of love, because it is followed by the greater responsibility of keeping the relationship alive. But none of these things happened that day because Rigoberto González’s poetry suddenly appeared on my shared screen at the outset of the meeting. It was a benign accident that marked the beginning of our immersion in the work of the Chicano poet of irrepressible sensitivity.

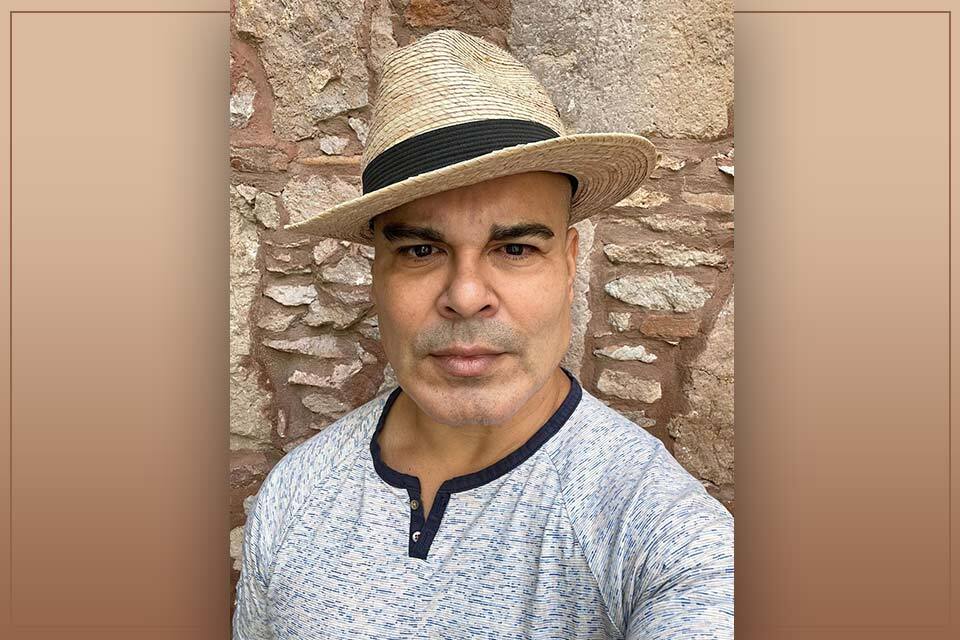

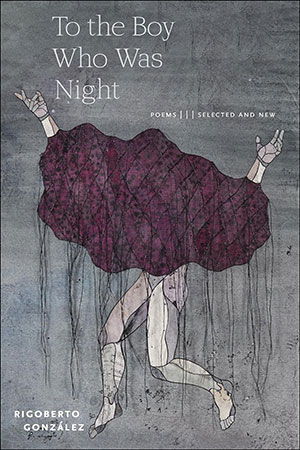

González is the author of twenty books of poetry and prose, including What Drowns the Flowers in Your Mouth: A Memoir of Brotherhood, which was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award in Autobiography. His most recent publication is To the Boy Who Was Night: Poems Selected and New. His awards include Lannan, Guggenheim, NEA, NYFA, and USA Rolón fellowships, the Los Angeles Review of Books Lifetime Achievement Award, the PEN/Voelcker Award, the American Book Award from the Before Columbus Foundation, the Lenore Marshall Prize from the Academy of American of Poets, and the Shelley Memorial Prize from the Poetry Society of America. A former critic-at-large for the LA Times and contributing editor for Poets & Writers, he is the series editor for the Camino del Sol Latinx Literary Series at the University of Arizona Press. Currently, he is a distinguished professor of English and director of the MFA Program in Creative Writing at Rutgers–Newark, the State University of New Jersey.

González is the author of twenty books of poetry and prose, including What Drowns the Flowers in Your Mouth: A Memoir of Brotherhood, which was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award in Autobiography. His most recent publication is To the Boy Who Was Night: Poems Selected and New. His awards include Lannan, Guggenheim, NEA, NYFA, and USA Rolón fellowships, the Los Angeles Review of Books Lifetime Achievement Award, the PEN/Voelcker Award, the American Book Award from the Before Columbus Foundation, the Lenore Marshall Prize from the Academy of American of Poets, and the Shelley Memorial Prize from the Poetry Society of America. A former critic-at-large for the LA Times and contributing editor for Poets & Writers, he is the series editor for the Camino del Sol Latinx Literary Series at the University of Arizona Press. Currently, he is a distinguished professor of English and director of the MFA Program in Creative Writing at Rutgers–Newark, the State University of New Jersey.

González’s life illuminates a magnetic vision of a decentered world with a reassuring intimacy. His poetry is a transmural stimulation of memory, language, and longing; the memory of a life lived, the language of a life ongoing, the longing of a life unlived. His struggle with the forces of racism and homophobia is daunting, but his decision to survive and thrive makes his life a tireless pursuit of justice, not only for himself, but for others who are victims of and become victors themselves in a radically racialized world. Writing is the currency with which he claims ownership of his place in the world.

González’s activism speaks to the influence of the daring life of his mentor Francisco X. Alarcón. Alarcón’s poem “For the Capitol Nine” was an act of solidarity in response to the demands of students protesting the state of Arizona’s Support Our Law Enforcement and Safe Neighborhood Act by chaining themselves to the Arizona state capitol. The piece made a lasting impression on me when I first read it five years ago. The poem, which Alarcón originally posted on Facebook, went viral and inspired other poets to lend their voice to the struggle. Alarcón left so much of himself in the world, especially in González, who continues to enrich the archive of American literature with works that demonstrate how poetry can provoke and sustain change.

González’s writing speaks to your experience, even when it is not intended for you. In “Rapist: A Romance,” he writes: “Our first night together I watched him sleep so peacefully I could have slit his throat.” I do not know what the poem is saying, but this line reminds me of a passionate coffee moment I experienced two months ago. One partner of the couple is Mexican, the other American. Upon our first meeting, the Mexican struck me as a poet in language and a philosopher in vision. Everything she said was a prayer, a song, a dirge. I imagined myself as Mexican when she described the earthquake in her village three days before our meeting, in which she lost members of her extended family, and some of her siblings lost their homes. However, when she said she knew her partner felt the anguish of her people but not as viscerally as she did, the owner and bearer of the loss, I then acknowledged that my presence in Mexico was only imaginary. When she confessed that she sometimes felt betrayed by her partner’s joy in her time of pain, I admitted that love cannot erase all our sorrows.

Again, I do not know what González is saying in “Rapist: A Romance,” and I will not ask him, because I am satisfied with how the poem makes me feel. However, I have asked González about other things: the labor and miracle of writing, the permanence and impermanence of loss and grief, the experience and monument of memory, the lightning of language’s entrance in his work. My friends and I may have lost an opportunity to “catch up” on the small details of our fascinatingly boring days, but we gained so much by joining González to bear witness to the liturgy and anxiety of ordinary lives.

*

Darlington: Good to have you here, Rigoberto. How are you?

Rigoberto: Hello, Darlington, great to be here. I’m doing alright, even though the world seems to be collapsing all around us. I just got back from an event with our graduate students at the MFA Program in Creative Writing at Rutgers–Newark. As director of the program, occasionally I have to offer a few words of encouragement because the chaos of the political world creeps into the sacred spaces of the artists, and I want to reassure them that we will survive this, as generations of artists before us have survived past travesties and tragedies. I believe the wording I used was, “In times of destruction, we must be actors of creation. Instead of despairing, let’s keep writing.” It was good to say that aloud because I needed to remind myself of that responsibility.

Darlington: We may never fully know the depth of history, life, and goodwill that accompanies such a simple act of kindness. Thank you for sharing and for inspiring your students. I suppose that Francisco X. Alarcón, whom you consider a mentor and to whom you dedicated your recent collection To the Boy Who Was Night, did something similar for you.

Rigoberto: Francisco was exceptional in so many ways. He was all about building community and making sure that we moved together as a group. There is safety in numbers but also comfort in connecting with people with whom you have something in common. For him, it was the space of the university, which could be isolating and alienating, particularly for those of us who were first-generation college students. It was not until I met him that I began to embrace several identities, like being Chicano and gay. Before that, I was still closeted and afraid that if I stopped calling myself Mexican, I would be letting go of my cherished past and family. Francisco taught me that I could be all these identities at once, that one did not cancel the others but in fact complemented them. I understood this through his poetry but also through his teaching, the books he brought into the classroom, the films he showed us, and the ways he encouraged us to be public and proud and present for others.

Francisco X. Alarcón taught me that I could be all these identities at once, that one did not cancel the others but in fact complemented them.

Darlington: I realize that in talking about death and the dead, we also talk about life and the living. May Alarcón’s legacy endure.

Rigoberto: Yes, it will endure.

Darlington: You have an interesting experience with your father, whose death inspired your collection Unpeopled Eden. You told Olga Segura that in the process of writing the book, you discovered that it was possible to recover and heal from the loss and trauma of your father’s separation from your mother and, eventually, his death. I think we can recover what is lost by remembering what is forgotten or repressed, and you have done a fine, diligent work of memory in your books. But before that abandonment, before that death, before that need to heal and recover, there must have been one moment of wholeness, of complete and incontestable joy, however fleeting, however distant now, in your childhood. Can we return there and see what is lost and what is recovered?

Rigoberto: I have a few precious memories of my parents with my brother and me. The best ones are probably from the brief time we lived apart from our extended family, just the four of us, in a small apartment atop the neighbor’s garage. That was quite the financial sacrifice for my father, and why my mother decided to return to work despite her ailing health—a decision that likely led to her premature death. That little space of our own was not without heartache—my father’s alcoholism, my mother’s illness—but for fleeting moments we were together, experiencing what I saw on 1980s TV sitcoms: a nuclear family gathered around the dining room table, exchanging accounts about their daily lives, and making jokes in the process.

Even then, I knew how rare such occasions were because the terrible times were never far from the happy ones, and that certainly shaped the way I remember the past and how I write it into my poetry, certainly, but mainly into my prose memoirs. What is lost is the hope that, no matter how ephemeral, the feeling of wholeness will take place again, if not the next day, then the next week or month after that. What is recovered is knowing that I have not forgotten what it feels like to be together, to be whole.

Darlington: It takes great courage to speak about one’s life. As someone who has written mostly nonfiction in the last five years, I know how hard it is to stare at your life on the pages or the screen. It is a mirror before you, a mirror you hold to your own face, so necessary an act yet so heavy an action. You are aware of this, too. I like how simply you describe the daunting task of creatively exhibiting the self in pubic: “Nonfiction is the most intimate space of exploration because autobiographical material is delivered at its most nude and vulnerable.” Yes, in writing personal nonfiction pieces, we face the world naked. In your case, writing the self seems like a necessary call to life and living. In your debut memoir, Butterfly Boy, you struggle with the sadness and loneliness of your emotional disconnection with your father, but in the sequel, Autobiography of My Hunger, you make peace with that reality and forgive your father for his absence. That’s a long journey.

Rigoberto: Indeed, that was a long journey. Butterfly Boy was released five days after my father’s death in 2006, which made it difficult to talk about the book because inevitably someone would ask, “So, what’s the relationship like with your father now?” And I would have to admit that he had just died, which put an end to any hope or expectation that we had reconciled or at least moved past our differences.

The last time I saw my father was in August of that year, just a few months before the release of the book in October. I remember telling my brother that after visiting my father, I was sick for three days. He said, “That’s interesting. Because our father was sick for three days before you got here.” After his death, my relationship to my brother worsened because I was racked by rage and guilt. My brother was with my father during his final days; I stayed back in New York, knowing that the money I would spend on airfare and lodging was best spent on unforeseen expenses. When my father slipped into a coma, with little chance of coming out of it, I wandered the streets of Manhattan, going into random movie theaters and picking whatever film was playing. When news of his death finally came, I was standing at a street corner, stunned and unmoored.

In the back of my head, I remembered that I was about to embark on an eleven-city book tour. I almost canceled that tour, but my editor and friend suggested that I make the tour part of my healing. I lost sixteen pounds on that tour, but traveling from city to city and sharing this story about my father provided a solace I don’t think I would have achieved had I stayed in bed all that time, wallowing in my sorrow.

Many years later, I asked my brother about my father’s last words, and he hesitated before revealing that before he died, my father had said, “I know your brother resents me.” That was painful to hear, but it made me realize that the burden was on me to forgive myself, first, and then make peace with my father. From that moment I began the process of forgiveness, which resulted in the key pieces about my father in Autobiography of My Hungers.

It made me realize that the burden was on me to forgive myself, first, and then make peace with my father.

Darlington: I am sorry, Rigoberto, but I am glad that you have found healing and forgiveness in this journey. I suppose the journey began in earnest when you left your family to thrive as a gay man. In 2013 you confessed to Bernard Lumpkin that this is the reality of most gay men, and that you were haunted by the emptiness this lack of familial love created in your life. Four years later, you told Kaveh Akbar: “When I was in my twenties, there were so many uncertainties and I felt like I was keeping my dream very small, or smaller than I think it should’ve been, because I didn’t see those examples around me. I didn’t see those opportunities for people like me. I say that as a Latino writer, as a queer writer, as an immigrant writer. So, I kept my dreams small.” Reading this made me think about the malleability of dreams. What is different now?

Rigoberto: Now I look back and realize that dreams are not to be measured but treasured. Even if I did perceive them as small, they were enough to keep me struggling to achieve them. I only thought they were small because I felt insignificant. Up until a certain point, I was still in hiding because being conspicuous led to unwanted attention, maybe even danger. I had certainly witnessed that at home—standing out meant being subject to criticism or ridicule.

That low esteem began to dissipate while living in New York and widening my worldview. I met writers fleeing persecution in Africa and the Middle East, artists seeking asylum from threats in Latin America, and activists fighting for social change at home and abroad. I knew the word community, but now I was part of various communities, and that was empowering. Being a queer, immigrant, Latino writer felt exhilarating for a change, and I was fortunate that people wanted to hear what I had to say and to read what I had to share.

Being a queer, immigrant, Latino writer felt exhilarating for a change, and I was fortunate that people wanted to hear what I had to say and to read what I had to share.

The other important difference is that I became an academic—a profession that I avoided for about eight years after my last college degree. I wasn’t keen on entering the university space because it seemed so insular and soul-draining. For many years I heard my professors complain that teaching and writing were not compatible, so I didn’t look for teaching jobs. But I was getting older, and I needed such vulgar things as health insurance, so I caved in and got a teaching job, only to realize that I had trained myself to manage my time so well that teaching did not get in the way of my writing. And there was a bonus: I got to meet and mentor young people who reminded me so much of myself at that age—a bit lost and looking for guidance. I absolutely adore my students, and when they graduate, I give them a blessing: “Go, and dream even bigger dreams than those I dared to dream.”

Darlington: Nigerian poet Niyi Osundare calls the classroom “a charmed space.” What you just described is certainly the charm Osundare beholds.

Rigoberto: This delights me.

Darlington: To the Boy Who Was Night opens with a symbolic poem that speaks about migration as a necessary act of survival. “The Flight South of the Monarch Butterfly” is an impressive, cartographic, and deeply arresting portrait of the journey of the famed North American butterfly. You know, there’s an expression that is used for putting people down: a butterfly that calls itself a bird. People who say this tend to suggest that a butterfly does not have the swiftness of birds, but the monarch butterfly does not agree. Like the bird, it cannot survive the cold winter of northern climes, so it migrates to the south during winter. It is natural that this butterfly has two homes. Two equally loved, equally valuable, equally embraced homes. That is part of its story, its reality, its life. It is striking how the story of this butterfly evokes the migrant’s life as an alternation between coming and going. Does this poem normalize this alternation, this double consciousness, as an ordinary, necessary way of living?

Rigoberto: The poem speaks to a condition of migration, particularly those who are labor migrants, as generations of my family have been—they were migrant farmworkers who did seasonal work up and down the agricultural fields of California. We had various homes there, but it was always understood that our one true home was back in Zacapu, Michoacán, a place we visited each year, where most of our relatives still lived. The monarch butterfly is particularly appropriate because Michoacán is also home to several butterfly sanctuaries, and I grew up seeing them flourish and eventually diminish because of deforestation and climate change.

When I wrote that poem, I also wanted to call attention to the grief of those left behind, those who waved goodbye to the workers who headed north. As a child I had to watch my father leave, knowing he would be gone for long periods of time, and seeing my mother worry that something might happen up there that would prevent him from coming back. Migration does not take place without risk, and certainly not without loss, or as the butterflies continue to teach us, without struggle. So, yes, learning to live in two or more places is necessary, and there is a richness to that experience. It certainly fueled my ability to imagine and create. But it is also a condition that brings much pain because no matter what home you inhabit, you’re eventually going to get homesick for the other.

Learning to live in two or more places is necessary, and there is a richness to that experience.

Darlington: The image of the feminine is impressively alive in your work. I was thinking about and really invested in the sadness and longing of women in “The Flight South of the Monarch Butterfly” who watch their sons grow, only to suddenly lose them to the allure of distant spaces.

But the feminine that is present in “The Slaughterhouse” is even more arresting. The poem wears the apparel of chaos and carries the voice of doom. Birth and death are happening with frightening simultaneity. There are dogs, pigs, and men. There is so much incoherence, so much blood and desire for blood; but there is also the surprising constancy and clarity of the present mother, whose life is ruptured and from whose ruptured life emerges a dark force that will rupture the world.

It is good that the poem opens with the caution, “listen,” but nothing is heard although so much is being said. And it’s confusing and mesmerizing at the same time. And you put it so well, so poetically: “Darkness can be so maternal.” What should we listen to? Tell me, because maybe I am not listening well.

Rigoberto: That poem, like much of my work that draws from a decidedly feminine presence, is inspired by the great loss of my mother when I was only twelve years old. For me, this absence is haunting. It is both a silence and a deafening roar—the inner and outer turmoil of grief. What holds everything together is the language used to express that experience. It’s a fragile structure, which is why poetry serves it so well since poetry is a construct of emotion.

My mother’s absence is haunting. It is both a silence and a deafening roar—the inner and outer turmoil of grief.

I wrote that poem so many decades ago—I was twenty-one years old, I believe. So, the pain of my mother’s passing was not even a decade away from where I stood at twenty: an undergraduate still uncertain about where he was heading in life, awkwardly moving into adult spaces and life-changing decisions. I was being inundated with new experiences and encounters with friends and strangers, so the only way to press pause was to concentrate on the page to determine what was worth holding onto or letting go. Listen, I beseech the reader, to the dust settling, and then look around to understand what in the world just happened.

Darlington: Communicating grief and horror is hard. I am sorry for your loss. But thank you for depicting the horror of the mechanized lives of immigrants in “Perla at the Mexican Border Assembly Line of Dolls.” The dehumanization of the immigrant, as Pearl’s story shows, can be packaged as work and as opportunity. It is horrifying that although Pearl “exchanged / her gentle touch for the rigidity” of the dolls, “she could not refuse this trade” that targets her sanity and life. Why? What is holding her down?

Rigoberto: For me, that poem is more about the financial trappings of being a wage laborer living in an expensive capitalist country. So, to make peace with the trap, one must find another way to articulate the American Dream to justify the sacrifice of having relocated to this country only to be met with disappointing results. This poem has been on my mind ever since I read an article in the New York Times about immigrant workers in Queens who have spent decades away from their families and homelands only to end up broke, without a retirement plan, and disconnected from their loved ones because they see themselves as failures. Yet they keep working because there’s nothing else.

It was heartbreaking to read about those folks because they reminded me of the times the school bus picked us up and all of us kids grew quiet as we passed the fields with all those bent bodies harvesting onions or lettuce. We recognized them—they were our parents, our uncles, our grandmothers—and they had no choice because they were Mexican, undocumented, without formal education or money. I have no idea if any other child on that bus avoided the same fate, but I certainly did, inspired by the horrible truth that there was no way out for many. However, some of us would get lucky, as I did, and find the road to another world, another life.

Darlington: We sometimes allow work to distract us from caring for ourselves. Such involuntary self-harm is often the forte of artists, but I like that you are conscious of self-care. At least, that’s what I make out of your response to Akbar’s concern about your decision to retire early. “Labor is important,” you said, “but so is living.” I think there is a time to labor and a time to live, and both are connected. You see, I started by asking how you were doing because I admire your reflection on living with ease. Looking back to a few days ago when you were awarded the Los Angeles Review of Books Lifetime Achievement Award, would you say it’s labor or the love of living, or both, that brought you this far?

Rigoberto: I must be honest about this and admit that it took some time to reach a point in my life when I was able to say no to a request or an opportunity and decline without guilt or feeling as if I was getting lazy or losing my spark. That moment came with age and maturity, and with the reality that as I was growing older, I was also getting slower. But even that wouldn’t have been possible had I not been as productive and prolific as I was.

When I was young, I was on a mission, completely committed to the practice of writing, and I wrote everything: stories, poems, children’s stories, essays, book reviews, interviews. And that hunger grew once I recognized that I had these publishing opportunities on several platforms: magazines, newspapers, and all kinds of avenues online. I always referred to this as my immigrant work ethic, a dedication to labor I learned from my family of migrant farmworkers. Work was what we came to this country to do, and the fruits of that labor were peace of mind and a respite from the financial worries that kept them awake at night. But the cost of that labor was physical exertion and burnout. As I mentioned earlier, labor is likely what contributed to my mother’s early death. So, one of the goals I had was to reap the rewards of hard labor that were not afforded to my family members because they worked so hard and earned so little. When I began to earn a notable living as a writer and professor, I made good on that promise by traveling to places my parents never got to visit, eating foods they never got to taste, and seeking adventures they never got to experience while they were still alive.

I always referred to this as my immigrant work ethic, a dedication to labor I learned from my family of migrant farmworkers.

I continue to live that way to honor their memories and to express gratitude for that fateful decision they made when my mother was nineteen and pregnant and barely making ends meet on the Mexico side of the border. They sat down at their small table and devised a plan to give their child a chance at a better future: they had no bank account, no property, no other valuables. “But we can give him citizenship,” they concluded. And with that, they crossed over, my mother as an undocumented alien.

My parents are both deceased, and I miss them terribly, but that journey they began many years ago continues with me. My journey is their journey, and this journey is still hard work, but it’s also a spectacular artistic life.

Darlington: And I am an inspired spectator.

Rigoberto: Glad to know, Darlington.

March 2024