Learning to Be Everyone and No One: A Conversation with D. Nurkse

After going for several long walks with Dennis Nurkse in southern Vermont where we both live, and reading his new book of selected and new poems, A Country of Strangers (2022; reviewed here in WLT), along with his elegantly innovative retelling of the Tristan and Iseult myth in Love in the Last Days (2017; reviewed here in WLT), I decided to conduct a series of interviews with Dennis that focused broadly as well as specifically on the arc of his unique career as a celebrated American poet and international citizen.

I learned that along with writing poetry throughout his life, often in stolen moments, Dennis possessed a strong altruistic commitment to working for the dispossessed and persecuted: devoting his time to Amnesty International, where he served as a board member; teaching prisoners at Rikers Island; mentoring underprivileged high school students in the New York City school system; and teaching college and MFA students at Sarah Lawrence, where he continues to work. I learned also that he is the son of an eminent Estonian economist who worked for the League of Nations but who tragically died of a heart attack when Dennis was only eight; that he grew up in both Switzerland and the US and has traveled widely to countries in Europe and South America and is fluent in Spanish, French, and English; and that he served as Poet Laureate of Brooklyn from 1996 to 2001. As a poet and student of poetry, he worked for years in blue-collar jobs after graduating from Harvard at the age of twenty before pursuing an unconventional, multifaceted career that was, to a large extent, reminiscent of the kind of work Walt Whitman’s “roughs” engaged in, working as he did in factories, lumberyards, and then, finally, the classroom.

The poet Philip Levine wrote accurately about Dennis’s spirit and voice in this pithy description of his poetry: “He possesses the ability to employ the language of our American streets, shops, bars, factories, and any place else, and construct truly lyrical poems, sometimes of love, sometimes of anger.” I kept discovering during my conversations with Dennis that not only were Levine’s observations correct but that so complex, colorful, and lapidary were Dennis’s poems, along with the details of his life, I had only really begun my conversation with him about both his work and his life and the exemplary way they complement each other in his poetry.

Love in the Last Days

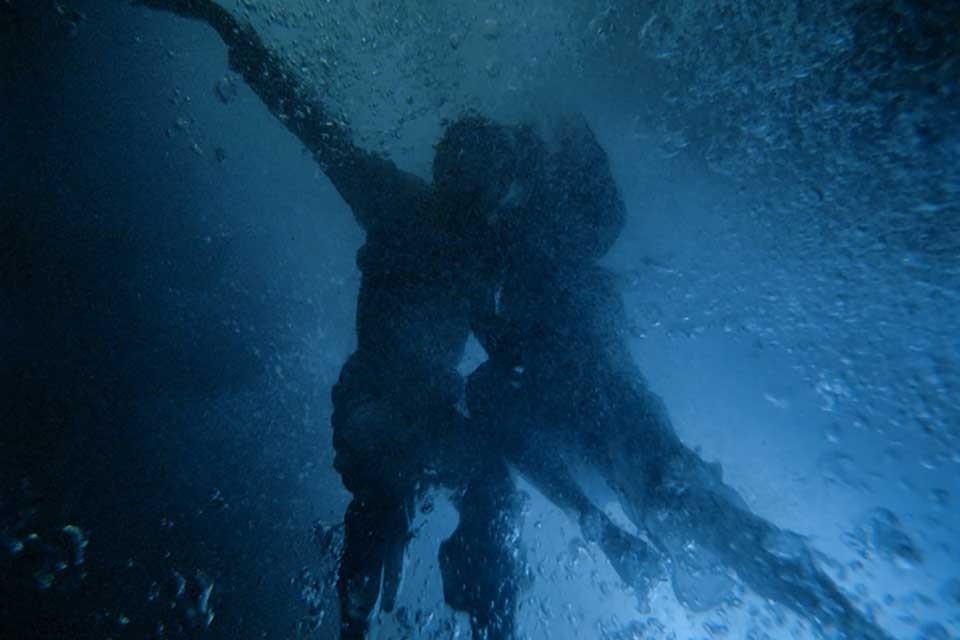

Chard DeNiord: You had the admirable nerve to write a new version of the twelfth-century love story, Tristan and Iseult, which you’ve titled Love in the Last Days and was published by Knopf in 2017. There are two early versions of this heartbreaking story known as the courtly and common branch, the latter of which has been lost, although there have been myriad other versions over the past millennium, including yours. Your version follows the common branch for the most part, which was written by Thomas of Britain and Béroul. In your version, Tristan’s beloved Iseult, not his wife Iseult of the White Hands, inserts a feminine conceit that reverses the romantic intent of the entire story, while at the same time providing an element of feminine wisdom that didn’t occur to either of the original authors or the myth’s subsequent revisionists. One could argue that Iseult is simply furious with Tristan for marrying Iseult of the White Hands, but there is more to the story than just that. Iseult doesn’t know that Tristan has not consummated his marriage with Iseult of the White Hands, for one thing. What prompted you to add one more retelling of this myth to the long list of all its other incarnations?

Dennis Nurkse: I’ve been interested in this myth since I was in my teens. I always wanted to write about it. It was a long-term project because some of it came to me intuitively, but since it’s a structured story, there were parts that I needed to fit in by volition and that I, with deliberate intent, felt as if it were in a completely different font and language. I had to do an enormous amount of revisiting of the myth for the book to feel natural to me.

deNiord: Tristan and Iseult is one of the most, if not the most, popular chivalric romances in Western literature over the ages and has been retold and rewritten dozens of times since its first incarnation in the twelfth century. How much research did you do for this book?

Nurkse: Yeah, I read a lot of medieval sources. There’s also a translation of Tristan and Iseult that was my main source; a translation of Bédier in English by Hilaire Belloc, who was strangely enough a right-winger. It’s a fascinating story to me, you know; maybe it was Denis de Rougemont who said Europe may collapse because the Tristan story is its myth and there’s so much death wish there. There’s a lot in it about self-destructiveness, as well as just plain destructiveness in the relationship between men and women. The self-destructiveness of men in particular was fascinating to me. I had to write all my books dozens of times, but the Tristan book I had to write hundreds of times over. I wrote versions that started out with the birth of the hero.

deNiord: But your tale doesn’t appear overworked. It’s a fresh retelling with a poignant, timely ending and just wonderfully evocative passages that evoke the wonder and sensuality of their love, such passages as the following stunningly beautiful passages:

At dawn she cleared her throat and wrapped her harp

in a cinquefoil wimple I’d given her and huddled

naked under jute in straw. I knelt beside her

until my knees ached, listening to her breath

in case I might interpret a catch.

She smelled of deer tallow with which she greased

her shanks against the cold, and crushed basil.

I thought I heard the exile harp answer her

From the direction of Brocéliande, modulating carefully,

Like a spider descending a thread, minor to diminished.

At last the sun rose, and tightened like a bass string

In withered alder branches, then slackened. It was day.

The finches sang freely, in pairs, each to each.

And there too I heard my name, forwards and backwards,

And hers, the King’s, and the hour of our death.

* * *

We explored each other and found our own spring,

taproot, firestone and deep shade.

We held our own court. Without rules of precedence

we flinched at a withheld glance.

We played chess naked, knight against queen.

the bishop was a slanting hornet, the rook a toadstool,

God the pawn who alone can change. The king

was a spindled leaf.

Nurkse: There were a lot of different approaches I had to write and then abandon because I could see that they wouldn’t work. That’s why I try to get my students to write without perfectionism: because you have to abandon most of what you write. If they’re perfectionists, then they don’t have enough ballast to jettison. Even most of the things I publish in magazines I have to abandon.

That’s why I try to get my students to write without perfectionism: because you have to abandon most of what you write.

deNiord: It must have made more sense to you that Tristan should die rather than Iseult. What new sense did it make to you?

Nurkse: I really can’t answer this without retrofitting more cerebral process than there was. It was more like a long slog through a swamp to write the book, but, you know, it started out as being a story about gender, about men and women and men projecting their fantasies, fantasies they may take for sincere emotions.

deNiord: Which is an old courtly conceit of romantic love followed by abandonment, rejection, and retribution.

Nurkse: I started exploring that, but I think some of the reversals that occur at the end were also explorations of class structure. I think of myself as a person who comes from a line of peasants, and my characters were aristocrats. They had ended up in the aristocracy, anyway.

deNiord: You don’t provide an explicit reason for why Iseult makes the decision she does to essentially execute Tristan at the end of the story by allowing the red sail to be raised, which falsely signals her demise, causing Tristan in turn to die of grief.

Nurkse: Yeah, there’s a theme of “I’m going to go because I’m faithful to our romance,” what they call ‘the adventure.’” So, “I’m faithful to our illusion,” that’s what you would say in Spanish; because illusion doesn’t necessarily mean I’m faithful to our fantasy but I’m also furious at you. It makes sense to me in terms of her character, but I’m glad you picked up on it because people just read the book and gloss over it.

deNiord: But I also sense there’s something else involved in Iseult’s shocking decision—the situation is also a portrait of her losing power, in my opinion—to raise the red sail, which is her realization that no viable future remains for her and Tristan. The decision you make to instill Iseult with the courage to signal this to Tristan, albeit indirectly but nonetheless resolutely, betrays this. Tristan dies on the cross of his obsession for Iseult. He keeps returning to Iseult, despite both his and Iseult’s departures from each other throughout the story, beginning with their parting in the wilderness camp in the wood of Morois, and then ultimately Tristan’s marriage to Iseult of the White Hands. Eros has an expiration date in your version of the myth, as it does in most tragic love stories. Your Iseult confesses, “I didn’t hesitate. I adore him. . . . Every great love has an obstacle. Ours was us.”

Nurkse: Absolutely. Male fantasy also is a real issue in the book. Tristan starts chasing imaginary monsters, although out of the purest of motives, but it’s a real drag for Iseult because she wants him to catch rabbits and build a home.

deNiord: Which Tristan ultimately fails to do in the wood of Morois.

Nurkse: Yes, which he is unable to do because he’s too noble and playing out what he conceived to be the role of the lover. But she is also a very problematic person in my book, too, as we see in her willingness to have her servant killed at the beginning of the story. The book doesn’t gloss over those issues. She’s a person who has power, but she’s in a vulnerable position in society and only has power if she uses it decisively, and she does, at the beginning and the end of the book.

deNiord: So you complicate the myth. Iseult can’t tolerate living in the wood of Morois, which in Tristan’s mind is a romantic landscape in the wilderness, but it’s also outside of culture. It’s an Edenic hideaway but also an impossible wilderness for Iseult to live in as a woman. She’s too far removed from her civilized element there. There are reversals and revisions that keep happening throughout the story in a fascinating way that remind me of what Giambattista Vico wrote about Greek mythmaking as opposed to Hebrew scripture, namely that the oral purveyors of Greek mythology kept reinventing their own origins, which seems very much like what you’re doing with the Tristan and Iseult myth.

Nurkse: Yeah, I was thinking of it as a contemporary book. Some people did get that.

deNiord: And the messenger’s torture at the end?

Nurkse: Well, he’s being tortured because he’s been telling this story about adultery. It begins with Tristan saying the king’s prisons will change you more than death, which is saying that you are in a very hierarchical world in which there’s state violence that represents control over the past, the future, and the afterlife, and then at the end of the book the messenger, who is also the narrator, is being tortured in the king’s prison.

deNiord: With thumbscrews.

Nurkse: Yeah, thumbscrews. The Israeli government documented abuses of the Holy Inquisition, and that was another research thing I did; a lot of that is very closely based on the Inquisition. All the torture details are based on the Inquisition. Which, of course, is not at all contemporary with the world of King Arthur.

deNiord: The message the messenger conveys is threatening to the society at large.

Nurkse: It’s a message of sexual liberation.

deNiord: The Tristan and Iseult story was written at a time when courtly love was challenging the institutions and traditions of the time with regard to romantic mores. So, what you’re reiterating about the tradition of courtly love is not new at all, but you’re rewriting it from more of a feminist perspective, it seems.

Nurkse: It fascinates me, that period. You know William IX, Duke of Aquitaine, declares, “Farai un vers de dreyt neant”: ”I will make a poem out of pure nothing.” You know, we don’t know quite that surreal tone before then, and we don’t know poems in which the women are the heroines or the protagonists before then, and of course there were female troubadours, the trobairitz, also; so it was a world that began suddenly, but “I will make a verse out of pure nothing” is just daunting to me— a moment of historical change.

deNiord: It must have been exciting to both “translate” and rewrite the ending of this myth with a contemporary awareness of its ending’s worn-out trope of tragic error like that of Romeo and Juliet as well as Pyramus and Thisbe. It must also have been enormously challenging in light of the myriad retellings of the story over the past millennium, yet it seems you reached a new understanding of its relevance to feminine strength, modern-day politics, and the arc of romantic history.

Poetry is all trial and error. I remember the errors more than anything else.

Nurkse: Poetry is all trial and error. I remember the errors more than anything else.

deNiord: You had fun with animals and objects in this book, giving evocative speech to fire, a dog, a spring, and a horse in the following passages:

Kindle me with oak. I blaze grudgingly.

A log chars to ash

and falls apart at one touch.

(from “The Fire”)

All night they moan, or choose not to, the horse farts

And I have no Other except a touch of gray along my muzzle

I can glimpse by squinting, maybe I too am dying of love.

(from “The Dog”)

Doesn’t God love them

because they are like him,

too broken to obey

the rules of death?

(from “The Living Spring”)

He thought of her, she thought of winter.

Or so I surmise. Her hand held the reins

With such subtlety I could have been ruled

By God’s will or the night wind.

(from “The Horse”)

Nurkse: I think the book wants to deconstruct narrative authority by letting even an acorn speak. Just as the characters don’t quite fit in their noble roles, the story finds its way into inarticulate sources. It even speaks itself. It’s a way of letting the story show its hand, an alienation effect. But I also feel everything in the world is wildly alive and talkative.

deNiord: Your familiarity with both medieval and present-day French enhances your retelling of this myth enormously, giving it a timeless quality. I know you lived in France for quite a while and that your mother was French. Did you think of yourself as a kind of modern-day jongleur when you were rewriting this tale? So many lines in Love in the Last Days exemplify your keen ear for the verbal music of Béroul and Thomas of Britain. I’m thinking of such lines as these:

Then the encounter was over.

We had slept together. Or not. I said good bye

as you might take leave of night itself. In the third watch

I was almost happy to be me, just another sword, paid off

with a title, allowed to doze armed cap-a-pie in the royal chamber

among the alaunts’ hot mouths, and dream of the king’s bed.

Alone I could almost see and touch her, when we made love

she was faes, the caul of the Absolute hid her naked body.

Did your translation, as well as your animal and element speeches, influence your own poetry writing in any way? I don’t think I would have guessed that the same poet who wrote the same spare, plainspoken poems in your previous twelve books is also the author of Love in the Last Days.

Nurkse: I’m not sure. Béroul is pretty pithy, monochromatic, even epithet-driven, in my opinion. Gottfried von Strassburg feels wilder and more lyrical to me. I don’t speak German, but I was influenced by the Penguin Classics edition.

deNiord: Love in the Last Days is as much about our contemporary world as it is about twelfth-century courtly love, specifically with regard to twentieth- and twenty-first-century feminist conceits and just how they redound on contemporary geopolitical politics events like George Bush’s invasion of Iraq.

Nurkse: Yes.

deNiord: And then the messenger in your coda who witnesses to the future of warfare and is tortured for his prophesying.

Nurkse: It is about torture. Certainly since Guantánamo. One of the problems with torture is that it makes the people who are tortured right.

deNiord: The fate of the witness, the messenger, who is also the storyteller, is to suffer the same fate as the hero.

Nurkse: Yeah, that’s the fate of the witness. It’s also, I think—you actually made this point to me—something that I had meant but what people didn’t pick up on very much: that the witness—that is, the narrator/messenger—is tortured, but the process makes the message endure. He’s dying, he’s telling you what happened, and the book ends in his mind—or in the minds of those who are killing him and witnessing his last moments.

deNiord: How difficult was it for you to write this book?

Nurkse: Well, it took so many years and I was so determined to write it, but there were so many times when I just couldn’t get it right, so that was liberating to write all the books, but there were books like The Fall (2004), which I wrote about the experience of sickness after I had recovered. It was therapeutic to write. You know, Love in the Last Days was a long struggle. I could remember times when I had the good luck to go to the MacDowell Colony where my project was to work on the book, and I worked hard and I didn’t get very far. I may have worked on it for two weeks and got part of a poem.

deNiord: It seems you had to discover something in the process of writing this book that was radical, from altering the dénouement of the story by killing off Tristan but not Iseult, to allowing the messenger to have the last word in the coda, to giving voice to a horse, a dog, a fire, a fountain, and the Holy Grail.

Nurkse: You read the whole book so you got it, and you realize that when the hero arrives at the land of the dead, the people who are there are the servant and the leper. It’s not Tristan’s lover who is waiting for him in the land of the dead. But some people didn’t read the book—they just looked at it and said, “Who needs another Arthurian romance?”

deNiord: Well, I think “we all do” is the answer to that. But Love in the Last Days is not just another Arthurian romance, although it’s contemporaneous with the first Arthurian legends.

Nurkse: It is more about things like the Vietnam War; it’s more about issues like torture and also issues like idealistic male fantasies that take place in the hierarchical class-structured world, which turn into nightmares even for the people who engender them.

deNiord: The Holy Grail plays a key role in the story as a vatic symbol that speaks, in the way other sacred objects or sites like the Delphic Oracle speaks to shamans or mythic characters. Could you talk a little about the vatic role the grail plays in Tristan and Iseult’s romance?

Nurkse: When the grail speaks, and it actually does speak in the book, just the way that fire speaks and the fountain speaks, the grail says, “Let go. . . . I am a cracked cup.” The characters are striving for perfection, and then the grail says, “There is no perfection.” In the body of the poem there are lines that say things like, “God is a broken man. God is a person and the loss of a person.” So the poem speaks for brokenness, but the characters are always acting for perfection or a wholeness that eludes them. So to answer your question, “What is the grail?”, the grail speaks and tells you, these characters are looking for perfection, they are looking for something that will give them power over themselves. Tristan is looking for the grail because he is a knight; she is commanding him to look for the grail because she is his lady.

deNiord: But that is all wrapped up in their romance. King Mark can’t do that.

Nurkse: Yes, but the grail, if you recall in the book, speaks one short sentence in very small print: “I am a cracked cup.” The other poem is a shape-poem in the form of a cup. It is a Zen thing. This grail they are all looking for is emptiness and brokenness.

deNiord: Can it also be a nihilistic symbol?

Nurkse: I don’t think so. The grail is more like Meister Eckhart’s type of emptiness. Everybody is trying to be full, but if you were actually empty, God would have no choice but to rush into you. You know what I mean? Meister Eckhart has that sermon in which he stresses that “detachment is greater than love.” But that’s what they don’t have. They don’t have detachment; if they found the grail it would be more like they noticed a cracked acorn among a million cracked acorns and then said to each other, “That’s what life is like; we should accept this.”

deNiord: Implicit in this painfully human story is the lure of Tristan and Iseult’s illicit love and where it leads them ultimately, into the wood of Morois initially, and then on a subsequent fantastical course of adventures in a medieval landscape that culminates inevitably in a tragic fate they seem blind to during their extended “affair” as the only possible conclusion to their romance.

Nurkse: Yes, very much so. A lot of the allure for them in the love affair, other than their mutual attraction, is the invitation to become characters in a story that is larger than themselves. When Iseult plays the harp in the forest, Tristan hears a counter harp answering her. In the original story they sense they are becoming mythic, which becomes evident as they act out their mythic roles. But in my story they are more human than mythic. We witness them sabotaging themselves as opposed to witnessing fate take its fatal course with them. They play that out and end up, as you were saying, in ambivalent positions. He ends up being an old guy dying of the plague with a fussy wife. She ends up being a woman on a boat with a bunch of recalcitrant sailors.

deNiord: Remind me how much time actually passes between the beginning of their relationship when they are young and fall in love and Iseult’s decision to allow the sailors to raise the fatal sail?

Nurkse: It is a fast forward, so the book dramatizes the intensity of the relationship because it presents forty poems to one year of their life, and then suddenly they are old. It is clear that all the adventures take place in a very limited time frame. It is chronologically clear that he is an old man at the end of book and they are both about the same age.

deNiord: So, in a way they have really carried out a long-term marriage, illicit as it is.

Nurkse: Yes. He went from about, say, twenty-five to seventy in my version of the myth. Youth to old age. The story doesn’t really tell you anything about her leaving her post, she is just giving up being queen. The story makes it feel as if she makes all the decisions. She rules. So yes, this elaborate adventure spans their whole life. I was not so concerned with including that part of the story which did not include both of them. Those episodes didn’t seem as important to me.

deNiord: Iseult ends up as the hero in your story. Does that word “hero” capture her character and identity accurately?

Nurkse: Yes, this has nothing to do with a particular story, but there is a book called All God’s Dangers, an autobiography of a sharecropper in the South—a guy called Nate Shaw—and it is his story. It is told to an anthropologist named Theodore Rosengarten. Anyway, the story begins with him as a young man fighting with his father; he loves his father, he hates his father. Very tense, complicated relationship, and when he gets into a fight with a white sheriff, he refuses to back down. He defends himself with a gun and gets sent to prison. He spends most of his life in prison. When he finally gets released, he starts thinking, “My father used to drive me nuts!” The book is almost entirely about the love-hate relationship with his father rather than the stuff you’d expect.

deNiord: Is there any other model for your version of the story? It is a little Shakespearean in some ways.

Nurkse: There are a lot of things that are deliberately unexplained, you know. Ophelia and Hamlet are defined by each other, but their universes never meet. There is a lot of eloquence between them, but also total silence.

deNiord: Did any of those influences occur to you?

Nurkse: I am sure they did but not consciously. Something I may have mentioned to you that I left out of the book but included in early drafts references something extraordinary that happens in Gottfried von Strassburg’s version of the story. Tristan has lost his position; he is in exile. He fights a giant and defeats the giant, and as penance, he makes the giant build a hall of statues. The statues are images of Iseult, images of King Mark, and images of the monster he defeated in the beginning of the story. And he goes to this grotto where these statues are and fights with the statue of Iseult; he insults and begs it and maybe slaps the statue of King Mark. And it is one of the strangest moments in literature, the process of objectifying or fetishizing your own experience. He is in love with this woman, and now he has literally made her into a statue that he begs and insults.

When I started to write the book it was really to investigate that scene. Among other scenes, this one really struck me as so much like the internet: creating an alternate reality and giving all of their lives to images and reflections while they grow older in a hall of mirrors and icons that they have created. It is too literary to build a book around. It was what first drew me to the story, but I had to leave it out because it was a little too over the top.

deNiord: The powerful dialectic between Tristan’s ongoing romantic delusions and his chivalrous deeds and conquests characterizes him as an archetypal hero who can’t resist a fight, but despite his heroism he has no idea what’s in store for him at the end of both his chivalric career and long romance with Iseult.

Nurkse: Yes, in the end, he is almost like a comic character who fights monsters no bigger than a prawn.

deNiord: And Iseult is as wily and ruthless as Tristan is heroic and quixotic.

Nurkse: Well, the version I’ve written doesn’t look away from the fact that Iseult has a scary side to her. The book is very clear in the beginning. I wondered whether to put this in the book or not, quite frankly. Most people read this and understood it as it was, but you are really digging into it. To me, it has a lot of emotional meaning; there is a sort of enormity that she has in asking her servant to sleep with King Mark instead of her, and then she tries to have the servant put to death so there will be no word or hostile witness. That is pretty amazing for a romantic heroine to do. And she explains, “I am protecting him and these days roll forward.”

She is seeing life as a chess game and she has to make the next move. She loves Tristan, but the alternative to him is to sort of be King Mark’s lap dog. She returns to King Mark the way Jane Eyre returns after she proves her autonomy, after she has a relationship with St. John. She is no longer just a prize. Does that make sense? The dog looks at them and says, “Tristan is manacled by his own arguments, but Iseult misses salt, bells, and his absence.” She is missing the opportunity to miss him. My version ends in deliberate ambiguity.

deNiord: In a way, she perhaps has more of a three-dimensional character?

Nurkse: Well, I think they are both three-dimensional, but she has more clarity and self-awareness.

deNiord: Is that because she is a woman?

Nurkse: Could be.

deNiord: She can’t live in the wood of Morois.

Nurkse: Right.

deNiord: She can’t even survive in the woods with Tristan.

Nurkse: She is always in a situation of contingency. When she says the days roll forward, she is saying there is one trial after the other, and I cannot be meek or passive. The book makes fun of Tristan’s bravery. When the book shows you Tristan in combat, he is just terrorizing the peasantry.

deNiord: So he is really more like an antihero than a traditional hero?

Nurkse: Yes, he is an antihero.

deNiord: If he is an antihero, then what is Iseult?

Nurkse: She is a little bit of an antiheroine also because she is a person for whom ethics would be a luxury.

deNiord: Did you mean for your retelling of this story to have some sort of contemporary message?

Nurkse: Yes, I did. I felt, what can I say? To me, it had a lot of resonance like Tristan in the forest fighting monsters who are a little bit like . . .

deNiord: Bush invading Iraq?

Nurkse: Exactly. Like Bush saying, “There are monsters in the desert and we will fight them and create democracy.” Do you know what I mean?

deNiord: It was kind of an old macho theme.

Nurkse: Yes. Very much this macho theme. It is like anybody can go to war, but I am a hero and I am going to go to war for love, justice, and democracy, and I am going to win.

deNiord: And as far as she is concerned, does she have a similarly ignominious trait?

Nurkse: I think it is very different for her. She is a sane, self-aware person in love with a compulsive man who has no self-awareness.

deNiord: Why is she in love with him?

Nurkse: Well, you don’t not love a person because they have no self-awareness. She doesn’t have a lot of choices.

deNiord: Who else is there? Mark?

Nurkse: Yes. From the point at which she first appears in the story, everything is against her will. She did not want to be on the boat with Tristan. She did not want to marry King Mark. That’s the first thing she says. She tells the reader and Tristan that she doesn’t want to do this, and it’s really foreshadowing. Tristan tells her that it is going to be so wonderful, there are going to be golden halls. And she just wants the real world. You know the comic passage in which he says to her, Well, there can be chamber pots and moldy curtains where you are going. He is trying to convince her that this will be the real world. Throughout she says she misses the simpler life she had in Ireland, she misses her autonomy.

deNiord: You know, that’s what you get for being a princess.

Nurkse: Yes, but everything happening in this story is happening against her will.

deNiord: Even the potion, the symbolism of it—they don’t fall in love because they look into each other’s eyes. They have to drink a potion.

Nurkse: Right, they both don’t realize what they had.

deNiord: It’s magical love.

Nurkse: Yes, and it is also important to note from a psychological view.

deNiord: Why can’t they just fall in love? They have to drink a potion.

Nurkse: Yes, but it is also true that the love affair is the only way they can distinguish themselves from the patriarchy. She is King Mark’s possession, and he is King Mark’s possession.

deNiord: In other words, the alternative is what? Something worse than what happens?

Nurkse: Yes, exactly. The love affair is how they are not just fulfilling their destiny as instruments to the king who rules by torture.

deNiord: I am trying to think about another similar myth that you might have been influenced by.

Nurkse: Well, it is obviously very different. We were just talking about the tension between the idealization of the story and living in the real world. That plays itself out throughout my version. Tristan is kind of like a Gilgamesh who never grows up. Monster killer.

deNiord: Yes, it is similar. Gilgamesh kills the monster Humbaba, guardian of the sacred Cedar Forest.

Nurkse: In Gilgamesh there is a movement toward self-awareness, but in this particular story it is the queen who has self-awareness.

deNiord: Right.

Nurkse: Yes. I got some reviews that said it was a really nice retelling and “a page-turner.” I don’t think it’s really a page-turner. It’s problematic.

deNiord: On every page of your version of the story there is an “oh no.”

Nurkse: Really?

deNiord: Yes. “Oh no,” they cannot live together in the wood of Morois. “Oh no,” Iseult is exiled to a leper’s colony. “Oh, no,” Tristan marries Iseult of the White Hands. “Oh, no,” Iseult raises the red sail.

Nurkse: They don’t really have many, if any alternatives. There was one review that called it “a knightly romp.” How can they call it that when she’s complicit in his death and the narrator is tortured?

deNiord: Right. There are a lot of casualties. The only characters who survive and live blessed lives are the animals.

Nurkse: The leper and the servant are on the holy island in the other world, and they made it. They all have speaking roles, which they don’t have in the original. And they make it to the other world even though they are poor.

deNiord: So, what are you saying about that?

Nurkse: The story is not ultimately about the aristocrats.

deNiord: In some sense, it is almost a morality play about the rich.

Nurkse: Yes.

deNiord: It has huge implications about the rich today.

Nurske:. I hope so.

The Frozen Present

deNiord: I’d like to shift from the twelfth century to your cogent, timely essay “A Frozen Present,” which was published initially in Poetry London and then in Plume. You wrote this prophetic essay when Trump was president. Do you feel we are on the cusp of entering in another dangerous era of a “frozen present,” and if so, what sane, prophetic voices do you feel are resonating courageously, like Henri Michaux’s, in opposition to the fascist lies that are recurring in America now?

Nurkse: There are many amazing poets who get very little ink. I think of Quincy Scott Jones and his book How to Kill Yourself Instead of Your Children. Rose Marie Berger’s Bending the Arch. I’ve just been reading Mervyn Taylor’s Country of Warm Snow. Poetry knows more about America than it did when I was a kid. That’s important if we want to survive authoritarianism. And yeah, Michaux wrote that sequence early in World War II. I don’t know if “enemy alien” is the correct term. Michaux was an interned foreigner in Vichy, France. Paris was occupied by the Germans, but he escaped to the South and wrote Au Pays de la Magie, which originally had a derisive reference to Hitler that the censor excised.

deNiord: Did you come up with the title for this essay or excerpt a phrase from Michaux?

Nurkse: I’m not sure. I think it’s probably my title, but it’s from several things; Evgenia Ginsberg, who was a political prisoner under Stalin, wrote about the beginnings of authoritarianism during Stalin’s regime. She wrote about “the years when the stopped clock always tells the right time because time doesn’t pass in a totalitarian state.” She was experiencing the same thing.

deNiord: How do you see or envision poetry acting as a corrective, or do you feel we’re stuck in that kind of stasis that was leading up to World War II? The poetry of witness unfreezes time in a way that wakes citizens up to the despot’s “frozen language.” The poet and activist Carolyn Forché has addressed this national sleep directly in her anthology of persecuted poets in the twentieth century titled Against Forgetting.

Nurkse: I don’t know. I mean, I haven’t given up, though I’m not sure it’s a corrective. I don’t believe that I could substitute myself for historical forces, but if I could help a few people understand and if they could help me understand, then I would say that was a great role for poetry. I think I was more just trying to understand the experience of fascism that we keep trying to refute intellectually—weren’t you talking about this a moment ago?—and you can’t really refute it because it’s more of a spiritual sickness or sexual sickness, you know, there are images that help me understand it. In that essay there was Eugenio Montale’s image of walking over a field, over insects like locusts, and they crunch under your boots like sugar, and I really got that sense of enforced complicity in violence, the creepy sweetness of the adrenaline surge, and that feeling of undifferentiation and trivialization. Marilyn Hacker speaks of a “sensual frisson.”

deNiord: To the point of psychosis, really.

Nurkse: Yeah, absolutely.

deNiord: Mass social psychosis.

Nurkse: You know that image of walking across a field and wherever you step you kill something, that image of disorientation and guilt and thrill of guilt, and the image of “they crunch like sugar” is also an image of infantilization. It is like one of the images in Michaux that I was interested in. Michaux talks about the horizon being removed, and that very much is an infantilization. In the unfolding of the description the speaking voice starts explaining in a more and more simple way, more and more inward-turning, basically babbling. Perspective and nuance have been removed. So there’s no control over syntax.

deNiord: Divorce from reality.

Nurkse: Now you have a discussion in which there is no real common reference, there’s deliberately no fixed point of reference. We used to argue about things like the Constitution or the national debt; now the discussion is regressive and personal and obliterates all those fixed social references that people once used to orient themselves.

deNiord: You write powerfully in “A Frozen Present” about the seductive political rhetoric that led ultimately to the Third Reich.

Nurkse: I’m not trying to, though. I think it’s more people like Michaux and Montale who are doing powerful writing, and I’m just trying to understand a little bit of fascist discourse because it’s such an open secret. In that essay I looked at the Dreyfus Affair. The lieutenant in the Dreyfus case slits his wrists and commits suicide, and the left thinks they’ve won because the officer leaves a little note confessing that he framed Dreyfus—but then Charles Maurras dreams up the headline “The Blood of the French Has Again Been Spilt,” reframing the suicide, subsuming it with the blood libel and the anti-Semitic nightmare from the Middle Ages. Now you have the followers of Eric Zemmour running around in France saying that Dreyfus may have been guilty. None of those things go away.

deNiord: The recapitulation is what keeps happening, it seems. I mean, even with Trump today.

Nurkse: That’s the idea of the “frozen present” too, you know, all these nightmares from the 1930s and then from the Middle Ages, cropping up unchanged.

deNiord: The past has a way of freezing the present with fascist precedents. In many of your books, I’m thinking of The Fall in particular, you write about family and others who are close to you, along with the oppressed. Your speakers often witness to the anguish and pain of another living thing, no matter how small, as in your prose poem “Under the Porch” in which you examine a fly whose wings have been pulled off but still buzzes somehow: “At last we reconciled ourselves and knelt with great compassion and watched as it moved in an almost line, then an almost circle, there in the crawl space under the huge brushes rigid with shellac: and we were rapt as if we’d found the way out of loneliness.” There is an agapic quality in this poem, as well as in several of your other poems. But I don’t mean to imply that your poems are in any way specifically or overtly religious. But with memorable poetic economy they effect a verbal antidote to inhumanity in their corrective, beneficent expression. And yet such language has had a sad history of being shouted down and even ridiculed throughout history by authoritarians. What humane rebuttal to fascist magniloquence do you feel poetry can provide, if any, in our age of resurgent autocrats?

Nurkse: “Magniloquence” is a good word. Poetry’s response when it’s telling is usually a humble one. I think of the anti-Nazi Poles writing in the 1940s—the only voice you hear is the voice of another human being.

deNiord: In book after book you write with an inherited sense of a recent immigrant’s perspicacity, sorrow, and wonder. Yet despite the refuge your father found in the US after fleeing Estonia in the early years of the twentieth century, you have carried a loneliness in your poems that has instilled you with what Keats called a “disinterestedness,” which allows you to capture the reality of the other, whether it be a fly, your father, a mental patient in a waiting room, or “an old couple eating saltines.” You cross over from yourself to others via a transpersonal self that divines both the physical and emotional reality of the other, even in what Robert Frost called “a diminished thing.” I see this as a consistent theme in all your books.

I think that’s what makes an experience powerful—the awareness of just how little space there is between us and death.

Nurkse: Well, thank you. I mean, it is sort of the presence of death in our lives, that contingency that we live in that makes an experience powerful, you know the degree to which every thought, every synapse, every functioning thing that you do is menaced, which certainly would have been borne into me by my father dying of a heart attack when he had never been sick for a day. I’d only seen him be seasick, and I’d been shocked by that. He died completely unexpectedly on a mountain in a field of flowers. I certainly felt the contingency of the body and then the fragility of institutions. My parents saw Europe unraveling.

deNiord: So, you were hit at a very young age with a profound sense of the closeness of death as well as your own mortality.

Nurkse: I think that’s what makes an experience powerful—the awareness of just how little space there is between us and death. You and I and everybody else on earth experienced this same “closeness to death” during the nuclear crisis that’s still going on. I’m aware of it every moment.

deNiord: Yes.

Nurkse: Although society has sort of gotten used to it.

deNiord: Numb to it.

Nurkse: Yeah, and you know it was at the beginning of President Obama’s administration that we were going to get rid of all nuclear weapons, and that didn’t work out at all. It makes me feel bad for God because God created us with free will so that we would love him of our own free will. It didn’t work out that well.

Learning to Be Everyone and No One

Learning to Be Everyone and No One

deNiord: Knopf recently published a book of your poems titled A Country of Strangers, containing new poems along with selected poems from all eleven of your books. How did you go about culling poems from your past books for this new and selected, and are there any poems in particular that you view as transformational or instrumental in leading you in a new direction with regard to subject matter, voice, or style?

Nurkse: I’ve always had to revise and discard work. It was a mitzvah to be able to do that with my editor’s support, for the sake of a concrete outcome. I wasn’t going to allow myself to agonize over a fortunate opportunity.

deNiord: In so many of your poems, I’m struck by your startling capacity for what John Keats called “negative capability” in a letter to his brother George, which he defines as the poet’s capacity for “being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.” Following up on this brilliant insight, Keats goes on to write in another letter to a Mr. Woodhouse that a “poet is the most unpoetical of anything in existence; because he has no Identity—he is continually in for—and filling some other Body—he is certainly the most unpoetical of all God’s Creatures.” In so many of your poems, your speakers engage in the paradoxical role of finding themselves by losing themselves in others. They place others before them, which William Blake claimed was the “most sublime act.” In opening to practically any poem of yours, one finds sublimely compassionate examples of transpersonal speakers who cross over to others with no “irritable reaching.” Could you talk a little about this selfless muse of yours who, like James Wright’s muse in such poems as “Hook,” “To a Blossoming Pear Tree,” and “Small Frogs Killed on the Highway,” crosses over to others with accurate empathy?

Nurkse: I don’t know! But I’ve often been surprised to find that, when I was in an argument, my poems took the side of the person I was arguing against.

deNiord: You also write a lot about children. I’m thinking of a poem like “Showers,” which begins: “The child tells me, put a brick in the toilet, / don’t wear leather, don’t eat brisket / snapper, or farmed salmon—not tell / orders.” The child, who is you as well as an actual child you’re addressing, often acts as your muse, ordering you to write about the mystery of quotidian things, which you then do with a combination of adult wisdom and childlike imagination, as in the conclusion of “Showers”: “Half measures, I say. She says action. / I: I’m one man. She: Seven billion. // If you choose, the sea goes back.”

Nurkse: I’m not trying to romanticize children. Maybe death is more real to them. They haven’t had the time to talk themselves into a trance.

deNiord: You also write a lot about your father, who died when you were eight of a heart attack. He was a world-renowned economist with the League of Nations and accomplished pianist who immigrated to America in the 1930s. You’ve written a lot about him in your poems. How would you say he influenced you to become a poet even though he wasn’t a poet himself?

Nurkse: On the last day of his life, he waved goodbye to me. I was too cool to wave back. My soccer teammates were watching. He was uncool, a parent. I planned to hug him in private that night. I never saw him again. The coffin was closed. Maybe poetry is a conversation with death. Certainly it’s a chance to say the things you never say the things you always think and never, never say in real life.

deNiord: And your mother, who was a painter.

Nurkse: She was very encouraging. She lived in a time when women were silenced. She never had a show in my life. I helped arrange a few shows after her death, and recently a scholar, Christina Weyl, rediscovered her youthful work. After almost eighty years.

deNiord: Your family was originally from Estonia. Who were they, and how did they end up in America?

Nurkse: My father’s family was Estonian and had lived in great poverty. I’ve been back there and seen where the family lived, you know, in the basement, they were descendants of serfs. They lived in poverty, my two aunts, one died at eight and the other at the age of twenty-four, and eventually my grandparents were swept up in the civil war, the Russian Revolution, but they came to Canada, to land grant Canada, and they had a little southern acre of forest—well more like prairie land—north of Edmonton, Canada. There was absolutely nothing out there.

deNiord: But you’ve been there.

Nurkse: I’ve been to both places, to Edmonton and the tiny town of Kaeru in Estonia where they came from.

deNiord: Your dad immigrated to the US in the late 1930s? He came ahead of the Nazis. He was a refugee who was swept up in the turbulence of the Russian Revolution, the wars of independence in Estonia. How much did Estonians suffer under Stalin?

Nurkse: Estonians suffered under Stalin, but my immediate family had left Estonia by the time the Russians came in 1945; they had left ahead of it, before the Germans were there. People in my family in Estonia have maps in which x’s mark people supposedly in Sakhaline, places in Siberia, but nobody has ever been in contact with them, so it’s just assumed that they’re still alive, as far as we know. They’re just crosses on a map.

deNiord: You think you may still have family in Estonia?

Nurkse: Well, I do still have family in Estonia. I’m in touch with them. I have a cousin who’s an art curator.

deNiord: Did your dad have to flee the Nazis in Estonia?

Nurkse: Well, at that time, my dad had been working for the League of Nations. He had been working in Vienna and had to leave Vienna because of the Anschluss. My dad could remember when he was in Vienna when Reds and Brown Shirts were fighting in the street. Nazis coming to power. I think it was very much part of my parents’ silence. There were a lot of things they didn’t want to talk about, that they didn’t want to expose us to, because they had seen that virus of ideas we see now, an irrational idea traveling from one person’s mind at warp speed to the next person to the next. You keep refining your arguments to refute it, meanwhile it keeps spreading and you realize its attraction is that it’s not rational. And its appeal is that it negates everything you stand for.

deNiord: So your dad must have been in his late teens, early twenties at the time?

Nurkse: I think he was older than that. He was born in, maybe, 1907; he died at fifty-two in 1959.

deNiord: It’s fascinating you’re still in touch with family in Estonia.

Nurkse: Yes, I’ve met them in Estonia. I know my family there. Some of my book, Voices over Water, was translated and published in the literary magazine Vikerkaar in Estonia.

deNiord: So, you grew up speaking a little Estonian?

Nurkse: Not at all. I grew up speaking French. My father was not a nationalist. After he died, I became interested in my Estonian origins. I learned a little Estonian but then forgot it.

deNiord: Do you know any today? Or can you understand it?

Nurkse: No, not to speak of.

deNiord: You have such an eclectic background as far as language and culture. I’m curious about the path you ended up taking, which is, in many ways, unique and quite different from the usual route of other poets of your generation. You went to Lawrenceville prep school in New Jersey and then Harvard, but then you decided not to attend an MFA or PhD program in favor of working as a laborer and human rights advocate.

Nurkse: Yeah, I did a lot of blue-collar work.

deNiord: What specifically drove you in that direction after college?

Nurkse: I think it was the times, you know—the war was horrifying and there was a certain fear of shame, survivor guilt for not being in Vietnam, and certainly shame at the idea of careers in the academy. I really felt that in a factory I could think for myself.

deNiord: In a way that you couldn’t have in a graduate program.

Nurkse: And there was sort of this political idea of “I’ll work in a factory and be part of the general strike.” I’ve written about this; I mean, I was certainly too shy to organize the workers in the factory.

deNiord: But you were deeply idealistic. You seem to have had two ambitions after college, to fight for social justice in practical ways and to write poetry. You succeeded at both. Over the past forty years you’ve published twelve books of poetry, written extensively on human rights, were elected to the board of Amnesty International USA for a 2007–2010 term, served as a program officer for the Defense for Children International-USA from 1988 to 1992, and worked as a consultant for UNICEF. Your study, At Special Risk: The Impact of Political Violence on Minors in Haiti, was commissioned by Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Service. You also taught poetry at Rikers Island Correctional Facility and in inner-city literacy programs.

I guess I was idealistic, or you could say traumatized.

Nurkse: I guess I was idealistic, or you could say traumatized. I was living in a country that was slaughtering the Vietnamese, and I had no way of understanding what my responsibilities were. I saw a dark side to the antiwar movement, or a painful side, things like the Altamont concert. As a kid I was idealistic, but I was aware that this was a right-wing country and the right wing had a lot of weaponry, so I wasn’t one of those kids who felt like “there’s going to be a revolution tomorrow and things will be great.” But I also wanted to learn about the country in a larger way than you get in school, whether you’re a scholarship student or not. I wanted to learn how people in America lived. I think there was a poetry of idealism.

deNiord: And you discovered that at Harvard by writing poetry and taking poetry classes with Stephen Sandy?

Nurkse: Oh, much earlier. I wanted to be a poet when I was like five or six. I remember some of my early poems, not to brag but . . .

deNiord: Please recite one if you’d like.

Nurkse: I had a poem in which the sky was deeper than the river and colder than the stone. I think maybe that’s my best poem so far.

deNiord: How old were you?

Nurkse: Maybe six.

deNiord: So, poetry was your essential avocation while you worked in factories.

Nurkse: I don’t know if it was so much an ambition to work in factories, but I didn’t want to view poetry as a career path. I wanted to be a pure poet, but I wasn’t into drugs, I couldn’t do communes. I needed to make a living. I was a political kid, so, working in factories, that kind of blue-collar work, was what was available, and it was interesting to me.

deNiord: That was an unusual and unorthodox step for a Harvard student to take after graduation.

Nurkse: Well, you know, at Harvard, I was living off-campus and the war was raging, the college would go on strike sometimes. It was a very different time. At that time, Harvard cost a couple thousand dollars a year, so it wasn’t as if I had mortgaged my future to get this degree.

deNiord: You were in a privileged atmosphere at Harvard. I’m sure most of your classmates went on to become lawyers and doctors and scientists.

Nurkse: A lot did.

deNiord: You also attended a prestigious prep school, Lawrenceville.

Nurkse: Yeah, but I was also in public school before that, and I knew a lot of kids in public school, and I was a scholarship kid at Lawrenceville. Back in those days they really made you feel it if you were a scholarship kid. But they have changed! Black faculty, an imamon staff, much more diversity. They told me, when I went to Harvard, that Harvard was going to be very diverse, but it really wasn’t; it was very privileged.

deNiord: What were some of the factories that you worked in?

Nurkse: I worked in a handbag handle factory, I worked in a factory that made steel products (screws and fasteners), I worked very briefly in a factory that made coat hangers, display cases. These were not life-or-death things; it wasn’t like we were going to strike and shut down the government because they needed our production. And then I worked in a lot of warehouses, one of which pulped returned magazines, which was an interesting job for a writer. There were just stacks and stacks of print that hadn’t sold that were going to be sent back to the pulp warehouse. The only literary magazine that was there was American Poetry Review. I remember always making a special little detour with my forklift to pick it up. I worked in a harpsichord factory for a minute and in Hartford, which was a very poor town at the time. I used to work for Kelly Labor, where they would send you out to a different factory every day.

deNiord: And this awareness inspires you to write with a strong sense of duende; what Federico García Lorca described as a dark music “that loves the edge, the wound [that] draws close to places where forms fuse in yearning beyond visible expression.” There is an acute but quiet sense of death’s proximity in your poems that instills your writing with memorable pathos. This is evident in so many of your selected and new poems in your new book, A Country of Strangers. You write very close to the bone, instilling your details and images with intimate significance that’s both deeply personal and universal at the same time. I’m struck by the “unique distance from your own isolation” that you establish in many of your poems in which you combine memorable descriptions of the austere nature of the officious world, as you do in your poem “Leaving Mary Magdalene,” where you enter the crowded, depersonalizing anteroom of the outside world where you learn “to be no one.”

Leaving Mary Magdalene

As I was signing out

a guard shuffled up to me

and put his frail hand on my sleeve

asking for discharge papers.

I emptied my pockets,

A snapshot of my child

Sweat-stained curling inward.

A Victory dime, a Wheat Sheaf penny.

A wisp of thread, a die, a comb.

I looked at him in terror.

He stared back baffled,

Angry I had no defense.

A radio was piping in Vivaldi.

I wanted to ask, was it arthritis

that gave him that constant mild tremor

and kept the buttons of his tunic open.

Finally he closed his eyes

and breathed: go,

as if my need were a force like time

and had exhausted him.

I swept up the pennies

and lint from the gleaming counter

afraid to say Thank You

and walked through the winking lights,

the heat shield, the self-opening gates,

into those ice-encrusted streets

where I first learned to be no one. (Poetry, March 1998)

There is terror in your traverse from yourself to “the other,” which you acknowledge when you’re gazing at the guard who is also a kind of psychopomp. As a poet who has staked out his own personal territory in both private and public ways in the various places and countries you’ve lived or written about, from New York to Brooklyn to El Salvador to France to Vermont to England to Estonia, you find a similar, interior home in your poems that’s also “not a home,” as Frost would say. Can you remember when you first developed this transpersonal sensibility and who some of your primary influences were?

Nurkse: Influences would include Lorca, Villon, Apollinaire. American poets like Randall Jarrell and Gwendolyn Brooks. I’ve always been interested in folk poetry, the blues, the Spanish medieval and flamenco poetry, coplas and riddles, which I came to translate.

deNiord: I’m fascinated by this paradox in your poetry: the speakers and denizens in your poems tend to be both fleshed-out and selfless at the same time, prompting the poet Craig Raine to write that you set “down the most intensely impersonal states with the coolest impersonality.” There is a powerful dialectic in your poems that traverses between intense embraces of the other and the indelible loneliness that haunts every individual. How would you sum that up in a single statement?

I think the loneliness of people in factories, public libraries, subways, giving birth, growing old, dying—that’s the only secret weapon the human race has left.

Nurkse: I think the loneliness of people in factories, public libraries, subways, giving birth, growing old, dying—that’s the only secret weapon the human race has left.

August 2022

Editorial note: Chard deNiord’s many interviews for WLT include conversations with Jane Hirshfield, Natasha Trethewey, Carolyn Forché, Major Jackson, and Chase Twichell. His interview with US Poet Laureate Ada Limón will be the marquee feature in the November issue of WLT.

D. Nurkse is the author of twelve poetry collections, most recently A Country of Strangers. He received fellowships from the Guggenheim, Tanne, Whiting, and NEA foundations, and was given the Literature Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. His work has been widely translated. He has also written on human rights, taught poetry in the prison system, and was elected to a term on the board of Amnesty International-USA. He teaches at Sarah Lawrence College and lives in Brooklyn with his wife, Beth Bosworth, and their wild puppy, Zephyr.