The “Irresistible Pull” toward Indigenous Identity in Probably Ruby: A Conversation with Lisa Bird-Wilson

Lisa Bird-Wilson is a Saskatchewan Métis and Cree writer and activist. Her debut novel, Probably Ruby (Hogarth / Penguin Random House), will be published in April 2022 in the US, following the August 2021 publication in Canada. Her short-story collection, Just Pretending (Coteau Books, 2014), was the 2019 One Book One Province selection for Saskatchewan. In The Red Files, her poetry collection (Nightwood Editions, 2016), she commemorates “the children who attended Canada’s residential schools, the survivors, and the ones who did not come home.” Told as a nonlinear narrative of shifts in time and multiple perspectives, Probably Ruby chronicles the impact of the foster system on Indigenous children through the story of a fierce, complex central character forging her own identity as she reclaims her Indigenous heritage. An adoptee to a non-Indigenous family, Bird-Wilson brings the drive and longing for family and kinship to fictional life in Ruby and, as the mother of seven children, to her own life.

This interview took place over Zoom and email during March and April 2022.

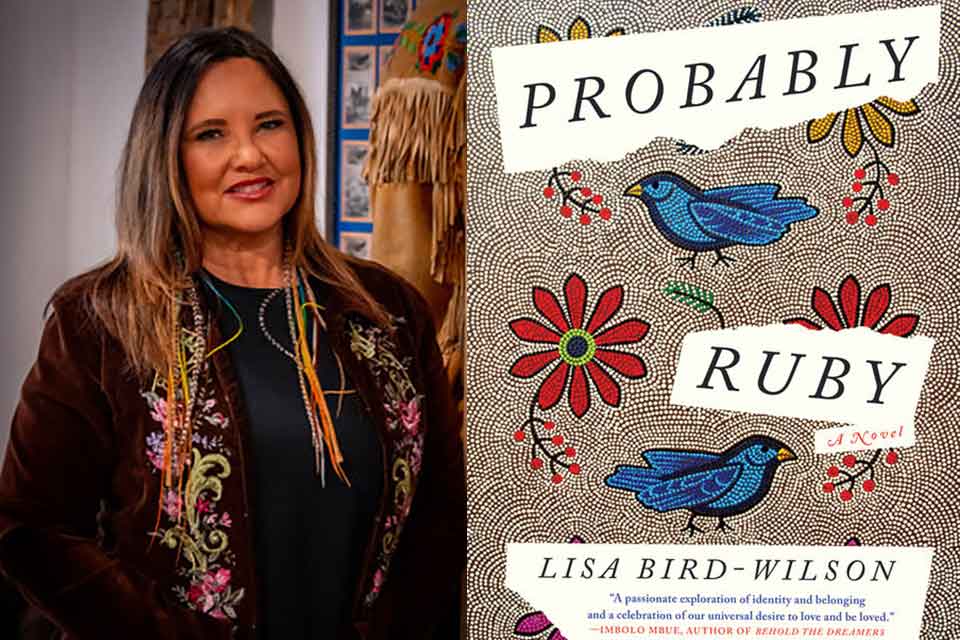

Renee Shea: Before we talk about the novel itself, I want to ask about the beautiful cover by Christi Belcourt. How did you find this powerful image?

Lisa Bird-Wilson: Christi Belcourt in the Métis world is very well known and famous for her artwork. In the other part of my life, I’m the executive director of the Gabriel Dumont Institute, which is a Métis-owned and controlled postsecondary institution that provides programs across our entire province. We also hold a collection of artifacts, artwork, and various pieces all connected to Métis culture, including the largest private collection of Christi Belcourt’s work.

Shea: So, you chose the cover?

Bird-Wilson: We had a lot of discussions. I really loved the way the publisher and editor wanted to connect with me about the cover—what was on it, what it would look like, what colors I like—even though ultimately the choice of the cover is not up to me. We had a conversation about what iconic images were Métis and danced around a lot of different things, like Métis sashes and beadwork. Then we landed on Christi Belcourt’s art, which imitates the beadwork of Métis culture.

Shea: The complexity of the beadwork seems a perfect entryway into Probably Ruby. It’s such an incredibly compelling story that it’s no surprise to hear reviewers repeating the words “heart” and “unforgettable” in their praise. But now, Ruby’s about to greet American audiences. What do you expect might be different in these readers’ responses?

Bird-Wilson: It’s a good question. But, because we’re still within that North American context, I think there’s a lot that’s very relatable. We have similarities as Indigenous people: wherever we are in North America, we’ve experienced colonization. I believe that experience will resonate across borders wherever Indigenous people have been impacted by colonial violence. For a number of years I’ve written from a Métis as well as a Cree perspective, but Métis are very specific more or less to Canada. (There are some American Métis communities in Montana and the Dakotas.) I thought that my Métis stories would work against me in the US market because I didn’t think there was much recognition of what Métis means as Indigenous people. When I talked with David Ebershoff [editor in chief at Hogarth/Random House], he was really interested in the idea of Métis and how Métis works in terms of Indigenous identity. He reframed it and made me see that this unique perspective of being Métis is something readers will want to know and learn about.

Shea: Since the discovery of the mass graves of Indigenous children in residential schools, largely Catholic institutions, public awareness and outrage have grown, though the cultural genocide that they represented was recognized earlier. That means you must have been working on Probably Ruby as this recognition was becoming more widespread. How did the unfolding of these events affect your writing of the novel?

Bird-Wilson: I’ve been writing this book since 2016 when I finished The Red Files, my poetry collection. But the “discovery” of the mass graves is not news to Indigenous people at all. Our communities have known forever that children died in those schools and children were buried there. You can’t be an Indigenous person here and not have a connection to those residential schools. We continue to exist despite that system, not because of it. Our people were not nurtured or expected to survive that system.

We continue to exist despite that system [of residential schools], not because of it. Our people were not nurtured or expected to survive that system.

Shea: I was so moved by your powerful essay “Ethical Remembering.” In that piece, you celebrate the survival of “a collective ethic of blood-memory-love where we rely on one another, exist in relationship to one another . . .” How does Probably Ruby fit into this idea of “ethical remembering”?

Bird-Wilson: That understanding of kinship and connection and interconnectedness, there’s a Cree word—wahkohtowin—that means just that: the interconnectedness of all life, our ancestors, and our relatives. It’s so central to Indigenous people and communities to understand that importance. When I think about Ruby, there’s the hard history—the graves, the residential schools, the “Sixties Scoop” of trying to take kids away from their families so that connection would be deliberately broken.

But I also think there’s the part about the memory of our families and ancestors, our land connections—those positive memories are our “blood memories,” not the trauma. That’s there and it’s in the background, and we have to deal with it. But I didn’t want Ruby to be trauma trauma trauma. She’s searching and wants to find her way back home; she wants to find her kinship and family and where she belongs. She’s continually building her narrative. If I had to pick one thing about the book, I’d say, “Family is everything.” For Ruby, sometime that’s even to her detriment. She has that boyfriend who knows how to manipulate her when he says, “I think I know your family. You look like somebody.” That’s hugely powerful stuff to an Indigenous person who’s been dislocated and isolated in this non-Indigenous family.

Shea: I never heard the expression “Sixties Scoop” until I began reading about the residential schools. It seems such an ugly phrase.

Bird-Wilson: I don’t even like using that term because it’s a shorthand for something that’s much more complicated, but I do talk about being Indigenous and being adopted. For a certain period of a time in history the residential schools were driving that agenda, of assimilating indigenous kids, breaking them from their family, trying to break their culture, and telling them they couldn’t speak their language. You didn’t really have that large child-welfare system where kids were being taken away from their families until about the 1960s, so that’s why the name—”Sixties Scoop”—came along and stuck for several decades. It’s about government interference with Indigenous people based on the concept that Indigenous families aren’t fit or good enough. The colonial myth is that as Indigenous adoptees we were “saved,” that we were disadvantaged children who were somehow neglected and in a situation that we needed to be saved from. Many Indigenous adoptees have now found that’s not true: we were loved, wanted, we were part of family and community—kinship.

Shea: You were referring to your poetry collection, The Red Files, when you wrote this: “I wrote as much with my heart as my head. More even.” Was that also true for the writing of Probably Ruby?

Bird-Wilson: Ruby’s my most favorite character I’ve ever written. I still can imagine her somewhere off the page just carrying on, doing what she’s doing. I wanted to embody her humanity. My intellectual side wants to tell you about colonial history and residential schools and the politics of being Indigenous in North America. But you can’t do that in fiction: readers won’t tolerate you being on a soapbox. You’re there to tell a story.

Shea: Ruby’s on a journey for sure—and it’s hard not to want to pull her back, tell her to stop, warn her—from some pretty self-destructive behavior with alcohol, drugs, and sex. You don’t shrink from describing the raw and hurtful, yet you never lose sight of the tenderness. So, we’re always rooting for her. How did you manage that?

Bird-Wilson: What I really like to do when I go to festivals or interviews or book clubs is read a little from the book. I want readers to hear how I hear Ruby’s story: which has humor, playfulness, a big personality, a big laugh, a lot of vulnerability, too. Ruby to me is such an alive character. She’s this very human embodiment of all that colonial past in history, but she’s here today—and this is the way that looks.

I want readers to hear how I hear Ruby’s story: which has humor, playfulness, a big personality, a big laugh, a lot of vulnerability, too.

Shea: One of the most fascinating things about the novel for me is Ruby’s “mythology.” She’s her own storyteller—the poetic story she imagines about her mother giving birth: “Ruby regularly applied herself to creating and owning the many fragments of her existence.” Ruby “attempt[s] to dream herself back together.” And this marvelous description: “her tiny nest of mythology” from which she “scavenged a narrative.” How did all these pieces come together for you?

Bird-Wilson: When I was writing the book, I didn’t even realize it was about one character for quite a while. I thought I was writing short stories. Once I put it all together and read it back, I realized that I wasn’t doing a very good job of differentiating the female characters because they all sounded like the same person. Then I realized that it’s all Ruby—one character. But it took me a while to figure out who Ruby is. I was often writing in a way where I was trying to please somebody else—whoever I thought my reader was. I was being way too (self) censored and edited.

Shea: I’ve read that the breakthrough into your understanding of Ruby was her laugh—her “royal, attention-getting laugh, big enough to be heard out in the waiting room.”

Bird-Wilson: Ruby’s living her life and doing so much searching. But she’s also learned to defend herself, to survive, to have that big laugh which does so many things. It shows people who she is; it’s genuine, but it protects her as well. Also, humor is a very Indigenous thing. There’s been so much trauma that we’ve learned to laugh: humor is survival. When I found Ruby’s laugh, it was like a gift: as soon as I saw her laugh, I saw Ruby and understood who she was.

Shea: This is a novel, not a memoir, yet there are parallels between you and Ruby. You were adopted by a non-Indigenous couple when you were only a few months old. In an essay, you wrote that they raised you “with the kind of loving severity common to the era” (“Born Red“), a fair description of Ruby’s upbringing. You repeatedly ran away, just as Ruby does. You’ve written and spoken about the search for your own blood family. Was it painful, helpful, sad—any or all of these—to relive some of your own experiences as you told Ruby’s story?

Bird-Wilson: When you write fiction, it’s hard enough to keep the momentum flowing, so I just went wherever my brain led me, knowing editing could happen later. I would hate to draw a line between my life and my fiction, but of course the influences are there; they just are not accurate or “true” in the sense that these particular things happened. In no way would I represent that this is my life. However, the phenomenon of the “Sixties Scoop” meant that twenty thousand Indigenous kids were adopted by non-Indigenous families. That is not my story alone. The Sixties Scoop era really represents an extension of the residential schools’ aims: to assimilate Indigenous kids into white societal norms and divorce them from their Indigenous roots. That is the painful part and the part of Ruby’s story that most accurately reflects my own—the pain and longing of that separation and cultural loss.

Shea: I have my own interpretation of the intriguing title, Probably Ruby. Could you talk about how it came to be?

Bird-Wilson: It came at the end. There were all sorts of other possibilities—I have a big list in my phone. Every time I was sitting somewhere with friends or having a drink, all these ideas would come up, and most were really awful. Finally, I realized the idea of Ruby’s insecurity about her identity is always there, so she’s “Probably” Ruby. Even in the book, there’s the moment she learns she had another name to start with, one that doesn’t even resonate with her. She’s continually needing to build her narrative. There’s one point where she’s talking with her grandmother and hears something else about Leon, her dad, that she didn’t know before. She just laughs because she can’t respond emotionally in any other way. She thinks she knows her story, she’s made her narrative in a certain way, and then she learns this other thing—and she has to go back and start again. It’s a constant layering as she figures out who she is. So, she’s probably . . .

Shea: One of my favorite passages is near the end when Ruby is thinking about meeting some of her blood relatives and likens herself to “a salmon swimming upstream. In her blood to go there. An irresistible pull. Only she didn’t swim away in the first place. That’s why it was so hard to know the way back.” Can you unpack that analogy—ending where you began? Beginning where you end?

Bird-Wilson: I haven’t really analyzed that very thoroughly! I think for me it’s the idea that somebody else has done this: Ruby didn’t do this to herself, and no Indigenous kids did this to themselves. And yet Ruby is left to fix it, figure out how to make it right, how to get back. And that pull is so “irresistible” because as Indigenous people we’re so tied to land, territory, where we come from. There are Indigenous stories and mythology because our understanding of ourselves is actually being born from the land, created from the earth. There’s a lot of spiritual significance to the landscape and geography. So, I just think that’s where my head was going with that: we’re very connected to where we come from.

Ruby didn’t do this to herself, and no Indigenous kids did this to themselves. And yet Ruby is left to fix it, figure out how to make it right, how to get back.

Shea: The power of language itself is a theme or leitmotif of Probably Ruby. Reflecting on N. Scott Momaday, you’ve written about the “force of language . . . to develop a renewed and reformed sense of self.” Could you comment on this idea in your own life or in Ruby’s?

Bird-Wilson: Each time I read Momaday’s work I’m so deeply moved by what he says and how he says it. Momaday writes frequently about the power of words and of exerting our language and our imaginations about our origins. As a person who was separated from my origins for so long, Momaday’s ideas are powerful to me. I don’t necessarily read Momaday’s reference to language as specific to Indigenous languages. In my case I am not a Cree- or Michif-language speaker, the two languages Indigenous to my family. I am an infant in terms of understanding Cree. Probably the first word I learnt to say was kokum, which means “your grandmother” (the first part of the word indicates the relational aspect of it—nokum means “my grandmother”). I understood kokum to mean “grandmother” because kinship terms in English don’t operate on the same relationship basis as kinship terms in Cree. (This, to me, is an obvious example of how worldview is wrapped up in language, and why preserving Indigenous languages is so important.) So, I’ve become accustomed to saying “my kokum,” which is like saying “my your grandmother.” I have employed the word kokum incorrectly for so many years that I hope Cree speakers will forgive me! The word kokum is wired into my brain. Momaday says, “A word has power in and of itself,” and for me kokum is a magic word that connects me to my family of origin. If I change now how I refer to and think of my kokum, I risk losing something sacred in my memory of and relationship to her.

Shea: I’m fascinated by “Ruby’s Relationship Web,” which is printed on the title page. It’s kind of like those anthropological kinship drawings or the depictions of generations of lineage in Faulkner or García Márquez. But those pretty much help readers to keep track, while Ruby’s “web” was, at least to me, almost inscrutable. How did this drawing come about? Is Tanner (the artist) a friend of yours?

Bird-Wilson: Tanner’s my son. He created it in multimedia with different textures and colors. What I found is that when you write a novel, it’s hard to keep track of what’s happening and make sure that you don’t make mistakes about how things fit together. I had a lot of back material helping to support my organization of what was going. One was a drawing of a stick figure—Ruby—in the middle and who was connected to her. There are people’s stories in the book that the reader knows even though Ruby doesn’t. During a meeting with an editor I worked with early on, I showed him the drawing, and he said, “It’s wonderful and should be put in the book.” We talked about it in terms of the importance of relationality—wahkotowin, that worldview of kinship. When I mentioned it to Tanner, he was excited to make a different representation of it but true to what I was writing. If you see his original work, it’s in about a thousand pieces: he layered everything together, which is a nice metaphor for Ruby’s life and relationships and how they build her story.

Shea: You bring many characters into Ruby’s journey as a kind of mystery or puzzle. Her mother and father are key, of course (and you tell her mother’s story so lyrically), but her grandmother Rose and “Johnny” are characters who lived the residential school nightmare—though with different outcomes. Rose just seems sad in how much of the assimilation she has accepted and passed on to her children, but the chapter entitled “Johnny” reads to me like a fable, almost a revenge tale. How did you develop these characters?

Bird-Wilson: I think Johnny’s story is different from the other stories. I see him as a kind of mythological character. So many kids ran away from those schools because it was so awful, some died trying to run away; a lot of kids were just picked up and brought back to the same nightmare. I wanted Johnny to be able to be successful. When I think about the children, even writing my poetry book, I wanted to find something positive, to show tenderness, to show all the things I felt were missing for them. Think about how lonely it was for kids to go to those schools. You’re a child, maybe six years old, you’ve been taken away from your family, your hair has been cut, you’re not allowed to speak your language, and then you’re physically abused on top of it—so many things.

I approach the idea of the children who are real people with as much tenderness and love as I can. For Johnny, there was a sense of having so much big power that those kids never had. So that’s the genesis of Johnny: he was able to go home, to speak his language, to be with his moshom (grandfather). Rose stayed at the school. She was there for a long time, and she came out of it the way so many kids did through no fault of her own. She wouldn’t teach her kids how to speak Cree because it was drilled into her that that is not something you want to do—you were punished for it.

We had a Truth and Reconciliation Commission across Canada starting in 2007. That commission heard testimony from survivors from residential schools and conservatively estimated that there were forty thousand children who died in the schools. But without the records, it’s difficult to know exactly, and that has been part of the desire of Indigenous people and communities to have access to all the records. There are a lot that haven’t been released yet. The Catholic Church is one area—the Métis delegation just met with the pope to talk about Métis attendance at residential schools and what it is that residential survivors need to happen in order to try to heal and recover.

Mourning Day

by Lisa Bird Wilson

these braids remember the women

trembling clump of girlflesh

eyes cast down and away

unfamiliar now

to one another

they mourn the loss of their hair dropped

like so many laments

clipped connections

to mothers, kohkums or aunties

who greased and wove

the glossy braids with steady

brown fingers

fat braids remember

cry like useless ropes on the floor

the girls long, at least

to step over them

in quiet ceremony

women-power mimicry

to mark the passage

a final regret

but cruel teachers clack heathen

and refuse to appreciate

these braids remember the women

from The Red Files / courtesy of Nightwood Editions

Shea: Pope Francis issued an official apology a few days ago. In the transcript I read, he expressed “shame . . . for the role that a number of Catholics, particularly those with educational responsibilities, have had in all these things that wounded you, in the abuses you suffered and in the lack of respect shown for your identity, your culture and even your spiritual values.” Why did the Indigenous delegation apparently not find that apology a sufficient response to their concerns?

Bird-Wilson: There have been a number of responses to the pope’s apology—all of them valid. From the media, it seemed many in the official delegations were touched by what the pope conveyed. And many articulated that this was just a first step. I, like others, was surprised that there was an apology at all—it’s been resisted for so long. What struck me immediately when the apology was reported and the translator said the pope’s words was that a couple of references made it clear that the blame was being placed on evil individuals in the Catholic Church; I noted the careful avoidance of recognizing the systemic role of the church itself in the residential schools. I think that’s an important omission.

I noted the careful avoidance of recognizing the systemic role of the church itself in the residential schools. I think that’s an important omission.

Shea: Rose and Johnny and other characters remind me that you started out basically writing vignettes; in fact, three of the chapters in Probably Ruby were published individually as short stories. When did you know that you had a novel? In the acknowledgments, you refer to Granada, Spain, “where much of this book came together.” How?

Bird-Wilson: I went to Spain with a group of writers. We had an apartment together, but we each had our own space. We worked individually all day and came together in the evenings. At home, I work a full-time job, so I spend weekends and evenings trying to fit my writing in. Spain was dedicated writing time, constructive time where I got a lot of work done. There was that moment when everything coalesced, and I realized I had a book.

Shea: No spoiler here, I promise! But the final scene feels pretty open-ended. As Ruby heads off to that wedding, she thinks of it as “where she’d soon find out how her concoctions through all those years, her family pictures, the partial stories she’s fleshed into narrative had turned out. Truth being only one measure.” What does that mean? Are you leaving readers with some existential question about truth? Is it a kind of happy ending but with a tease?

Bird-Wilson: That’s a good question . . . maybe it’s a kind of pushback against the capital-T Truth. I don’t know that Ruby will ever find exactly what the “Truth” is. What’s wrong with the pretend pictures Ruby puts on the wall for her kids? For Ruby, the important part is that there’s family, extended family relationships and kinship. Maybe it goes back to the very first time when she’s able to take one of those pretend pictures off and put the real picture on the wall and tell her kids about it. She’s been trying to do that for her whole life and to make sure her kids get connected—because she missed it.

Shea: So maybe you’re not through with Ruby?

Bird-Wilson: I’ve asked myself if I might write more Ruby. Who knows? Right now, I’m working on a memoir, and I’ve had a few pieces published that will become part of it. But we’ll see. I do think there’s more for Ruby to say and discover!