“I Write about People Whose Lives Are on Fire”: A Conversation with Sandra Cisneros

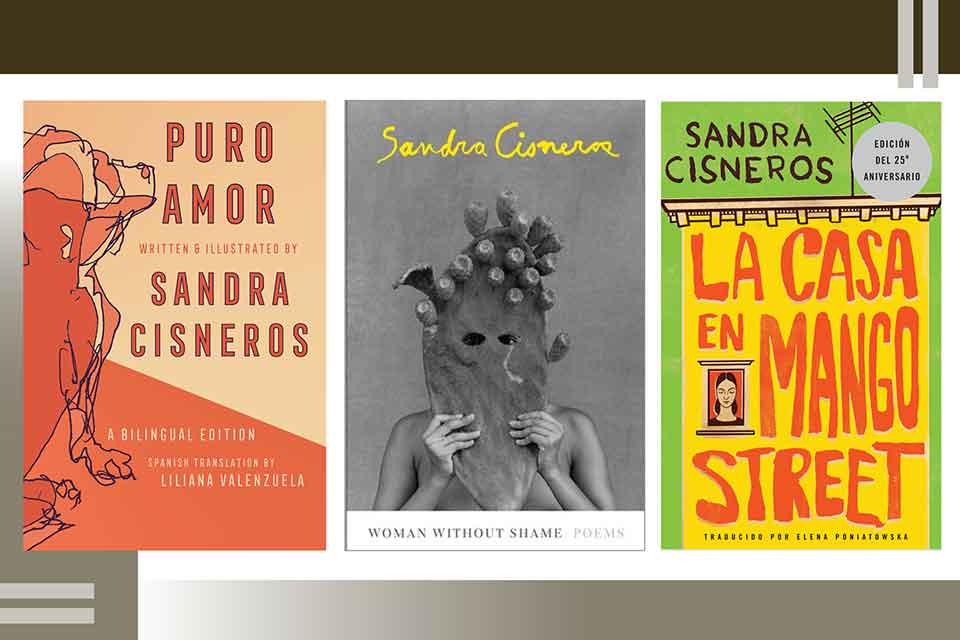

Sandra Cisneros’s success as a poet, short-story writer, novelist, and essayist is tied to her determination to write about others with awareness and love. Her work is populated by powerful people—powerful in their pain, joy, and hunger for home. This fall, Cisneros’s poetry collection Woman Without Shame will be published in English by Knopf and in Spanish by Vintage Español. We spoke ahead of UC Riverside’s forty-fifth annual Writers Week, at which Cisneros received the Lifetime Achievement Award.

As we settled into our conversation by making not-so-small talk, Cisneros commented: “We have a very profound connection with landscapes, and when we’re born into the wrong landscape, we feel it.” When I told her that’s what makes me nervous about the idea of leaving Earth for another planet, her response captured the service-minded spirit with which she’s lived and written: “Yes, absolutely. I feel like traveling south has been a return for me to an ancient DNA that wanted to come back. The people that ventured far away and couldn’t come back—I came back for them.” Cisneros’s writing offers an opportunity to return to ourselves and the places from which we came.

Emily Doyle: The concept of home seems to inform much of your work. In your memoir, A House of My Own, you say you knew “little about how women writers lived” and “even less about working-class writers.” What has living like a writer meant to you, and has your idea of living like a writer changed over time?

Sandra Cisneros: Well, when I was young, I didn’t really know any women writers from the working class. The difference of woman writers and class wasn’t something I was conscious of, but I was very aware of being drawn to writers of the working class like Carl Sandburg and Gwendolyn Brooks, both from Chicago. They were very much in my mind when I was coming up. I felt very connected to the poems they wrote and the neighborhoods and kinds of people they wrote about. There was a kinship there. I felt they were my literary family. But I didn’t really know how writers lived. It was a mystery to me.

I’ve had to edit, stumble, and fumble to find my way. . . . It’s important for young women to know it’s all about how you get up from those failures.

Gradually, I had to dismantle harmful images that are still going out there to young women about how to be an artist. I really hate when I see movies where someone travels around the world and they just become writers by living in a beautiful apartment in Manhattan or some wonderful house in Greece. I would scour their bio notes and think, How did they get the money? Where do you get the money and permission to do that? I just couldn’t figure it out. And we’re used to reading about men. The Hemingways and the Faulkners. You don’t get the Jean Rhys stories until very late. Then you say, “Wow, she really had a hard life, no wonder she turned to drink.” But when you’re young you get these romanticized versions of how a writer lives. Even for the men, it’s all romanticized. I wish they’d give you the reality for those of us who come from families where parents can’t help us, where we don’t have a trust fund. They’re not going to pay for our trip to Europe or rescue us with credit cards because they don’t have credit cards. It can be dangerous because you start imitating models of people who have more networks and more means.

When I won my first NEA [National Endowment for the Arts grant], I said, “One ticket to Europe!” I didn’t know what I was doing. I thought that you became a writer by traveling. And all those ideas of how a writer lives you have to invent. So, I did get the house like in the movies with the typewriter and the mountain where she’s tap-tap-tapping. I did live like that for a month because I had a grant. But for the rest of my life, I’ve had to edit, stumble, and fumble to find my way. I’ve done some fumbling and stumbling, some really horrible mistakes, some things that left me rather damaged. But I was able to survive my mistakes. It’s important for young women to know it’s all about how you get up from those failures. The mistakes are inevitable. Because that’s how we learn. We don’t self-destruct, we don’t harm ourselves, we don’t detour from our destiny because of disasters. We say, “Okay, I made this mistake. I forgive myself. How do I get up from this and keep going? How do I keep going forward?”

Doyle: Have you had to fight an urge to self-destruct?

Cisneros: Yes, I think artists are especially vulnerable to harming ourselves because our depressions are so intense, just like our joys are so intense. And we have to understand that that’s part of our sensitivity and being-ness. It’s our profession to feel things deeply and profoundly. We should engage ourselves with other people on the planet. We’re like a canary in the coal mine. That high sensitivity is what allows us to guide the community and find language for things that don’t have language. It took me a while to understand that.

When you’re a child and you have this hypersensitivity, it’s brutal because children make fun of you. A teacher looks at you the wrong way and you burst into tears. You’re the girl who cries all the time. Maybe your mother’s frustrated and says, “Why can’t you stop being such a big baby?” I have a manuscript, a children’s book, that’s not yet published about being the crybaby. It’s very important to tell those children that the crybaby has a job ahead of them. You’re the crybaby because you’re also the baby who teaches everybody how to laugh. You delight in everything.

For me, I can’t walk away from a stray animal. I wince if someone tears a leaf off a tree or hurts a plant. All of these things around me are alive and spirit-filled. That’s hard to explain to people who aren’t writers, poets, or sensitive artists. You have to grow into realizing, “Oh, now I know why I was a crybaby. I’m still a crybaby, but now I know it’s for my profession.” It means you have to be very kind to yourself when you do go into those nosedives. You have to know how to take care of yourself so you don’t self-destruct. You have to seek the people who can heal you. You have to know it’s part of your nature that you’re going to have those nosedives. It’s all right. You’re not crazy. You need to be as tender and as kind to yourself as you would be to others. That’s something I’ve learned.

We’re like a canary in the coal mine. That high sensitivity is what allows us to guide the community and find language for things that don’t have language.

Doyle: You’ve shared before that you wish you had asked journalist, poet, and author Ryszard Kapuściński, “Does a writer have to live in a perpetual border in order to be able to see?” I’d like to ask you a version of that question now: What does it mean to live in a perpetual border? What might doing so make visible?

Cisneros: That’s a nice question. Nobody’s ever asked me that. Well, Ryszard Kapuściński was always viewing things from this space of an amphibian, of being between places. He wasn’t quite of the community. He was watching things from an outsider’s point of view. But I think all artists are outsiders. Don’t you? That we don’t quite fit in? We don’t want to be outside but that’s where we get relegated. It’s because we have to be witnesses. It’s important for us to be witnesses because the people who are the actors are sometimes talking so much they don’t listen.

There’s a humility that’s necessary to being an artist, or maybe to being a great artist. I gauge great human beings on their humility. I think that great artists—I’m going to say this and maybe I’m wrong—have to have some sense of humility in order to respect everyone else. If you don’t have that, you have this big old ego and think you’re better and smarter than everyone else. And Kapuściński had that sense of inferiority and humility. It gave him a power, a kind of sacred voice that I like in his work. That humility is part of what made him great and allowed him to write from such a compassionate and wise place. Maybe people who don’t have that humility are never going to reach wisdom, you know? A spiritual wisdom. Everyone’s on this light path, I think, to gain spiritual awareness and to go forward in this race that we’re on in our lifetime—not competing against anyone, just moving forward.

The writers and artists who I admire have a great deal of humility and awareness—Vincent van Gogh, for instance. You can see that in all of his writing. Ryszard Kapuściński. Elena Poniatowska. I asked Elena, “What do you want to accomplish before you die?” I thought she was going to say, “Oh, I want the Nobel.” But she said, “I want everybody in Mexico to go to sleep tonight having eaten the same amount.” That answer me sacudó, it just shook me upside the head. It wasn’t about her. It was about everybody eating, not going to bed hungry. And to me that’s her humility. That’s a wise woman. I’m sorry, but the ones that get the big prizes, the Nobels, are not always the wisest or most wonderful human beings to me. So those prizes are moot.

It’s important for us to be witnesses because the people who are the actors are sometimes talking so much they don’t listen.

Doyle: There’s something to stepping back from the self.

Cisneros: Yes, that’s right. I think great writing is about dissolving your ego. Getting out of the way and really channeling your highest potential, and I think that can’t happen if you’re thinking, I want to win this prize or What will they say? I’ve found that those questions get in the way of my writing. I can do great work if I disappear. And that’s really hard to do. But you have to try every time you write. Just get out of the way.

Doyle: In the introduction to A House of My Own, you say that you need your animals to write, explaining, “When they are with me, I am home.” What is the relationship between your animals and home? And what renders their home-giving presence vital to your writing?

Cisneros: When I was younger, I wanted to get to these writing residencies like Yaddo and Hedgebrook. Now I don’t want to go there because it would be a punishment to be away from my animals. I don’t want to go to any place that would prohibit animals because to me they are as important as my laptop. They make me feel calm. They give me these big generous doses of love that calm me down.

I think as women writers we need to feel safe in order to play. My animals, they play with each other, they make me laugh, they make me feel safe. That’s very conducive to writing, to be in some playful frame of mind. That’s how they help me. Just like if I go to the market and get a whole bunch of nardos (tuberose) and some purple roses. I put them in my room, and every time I lift my head they make me go, “Ah.” My animals do that.

Doyle: I love that.

Cisneros: Yeah, my animals calm me down. They do something to my energy that makes me feel so lucky. And they know if I feel bad. They interrupt me sometimes but not much. They don’t need a lot.

Doyle: I have one more question that has to do with home. Concerning your former San Antonio house, once called “The Purple House,” you’ve written: “I don’t realize how much it’s inspired me until after I take a good look at my house with its niches and cupboards peopled with plaster saints and clay putas, its shelves of Mexican toys, its sense of humor juxtaposing high and low art, its operatic over-the-top drama and tongue-in-cheek camp.” This passage has led me to wonder whether you’ve always derived inspiration from juxtaposing “high and low art” and how, if at all, such a juxtaposition might have invigorated your life, spirit, and writing?

Cisneros: You know, I’d gone to Texas in ’84, but I came and went because I had to make my living by leaving Texas and earning money in other states and then coming back and spending it there where it was cheap. I had low overhead in San Antonio. But it wasn’t until the early 1990s that I dug in, settled down, and planted roots. That was when I met a community of visual artists and folk-art sellers who had a sense of aesthetics and delight in the coming together of the US and Mexico. All these artists worked from that amphibious state that we were talking about with Kapuściński. They made me aware of that loamy and rich borderland between cultures.

I’d never lived as close to the border as I did in San Antonio, where I had these visionaries who inspired me. They’re the ones that brought me to the attention of high and low art and code-switching. They educated me about things I hadn’t grown up with. They reintroduced Mexican traditions that had been lost to me. We delighted and inspired one another. I have to give gratitude for this community of artists who were my colleagues. I want to write about them some more in the next book of essays I’m working on. I want to write about how important they were to me and I was to them when it comes to ways of seeing—I’m quoting John Berger here. It was precisely a way of seeing the world from a multiethnic position, crossing borders of color and class—and sexuality because a lot of my friends were gay. It just made me look at the world in a new, kaleidoscopic way. Backward and forward, the past and the future and the present. I think it was one of the most fruitful times in my life. We used to say, “We live like millionaires!” And I remember saying, “We don’t need the Left Bank. We are the Left Bank.”

There was a new creative energy that was going on at that time. Not just in the visual arts—my friends were mainly visual artists—but in music, too. You had some very cool musicians coming up. San Antonio was so funky, in a way that Austin was losing its funkiness. San Antonio was affordable to people who were cutting-edge and doing things with conjunto music and painting or sculpture. It was just a good, affordable, safe place to live. Not anymore, but I’m talking about the early ’90s. I was very lucky to have this community.

Doyle: I’d like to talk more about your beginnings. You arrived at the Iowa Writers Workshop as a poet and soon began writing fiction as well.

Cisneros: Correction. I arrived there ambidextrous, but I had to declare fiction or poetry. The only reason I declared poetry over fiction was because I had studied with a poet but not a fiction writer. I didn’t feel my fiction had been edited to the point that I felt confident to apply to fiction. But I always felt that I did both. I began a career in poetry, but that was by default.

Doyle: I see. Then I’m curious about your relationship to writerly labels like “poet” or “fiction writer” or “nonfiction writer.” Have you thought of yourself at times as more one than the other? How, if it all, has your relationship to these labels changed over time? And have you found that occupying one label over another makes some work more possible, other work less?

Cisneros: I think the most difficult genre for me is poetry. I began writing poetry as a child. Then I went into fiction, then back to poetry in high school, and poetry as an undergrad with a little bit of fiction. I always felt I could do both, that they were different but that I was able to manage and was attracted to both.

I feel that the basis of my writing is poetry. You know, like the layers of Troy. One of the base layers is poetry. But as I get older, I try other things. I’m working on a libretto right now for an opera with Derek Bermel. And I started drawing again. There are other genres I’d like to try. I think the genres are interrelated. Poetry is like ballet, and, for me, it’s the basis of all my writing. I’m very lucky I had that as my foundation. I like to call myself a writer because I feel like I can do lots of things. I’d like to try different things—maybe a play, maybe a screenplay. I don’t know what I’m going to be interested in tomorrow. I really don’t have a lot of time. I’m sixty-seven so I need to focus. I don’t want to start a whole new career, but I want to become a better writer.

I feel that the basis of my writing is poetry. You know, like the layers of Troy.

Doyle: Recently, you used your own drawings to illustrate your bilingual chapbook, Puro Amor—the first time, I believe, you have ever done so. Can you discuss your decision to illustrate your work?

Cisneros: We offered the drawings to the publisher. I’ve been drawing since before I knew how to write my name, and I never stopped drawing. I drew in high school. And in undergrad I took every semester, as oxygen, a class that I liked, and it was always a studio class simply because I felt so happy there. Everything else, I wasn’t so great in. But I was really good in art classes. I would get A’s in those classes. That should tell you something.

Most of my friends who are artists can do more than one thing. My friends who are composers can also do something else. And my friends who are poets can also play an instrument. Like Joy Harjo, who plays the saxophone. Before that she was a visual artist. All my friends are kind of ambidextrous in that way. So, I think it’s coming from the same place. It’s just a matter of mastering the tools.

I always had this desire to draw. But you know, I would draw, and my friends who were artists would ask for them or I’d say, “Would you like this?” When this book came around and we offered them drawings, I realized I didn’t have any because I’d given them away! I had to ask everyone I’d given them to, “May I have that drawing? May I get a copy?”

Doyle: I’m surprised to hear that the illustrations for Puro Amor already existed because it seems like the relationship between the text and the images is so tight.

Cisneros: Oh, really? That’s nice to know. I do want to draw more. I draw people, too. It’s just that the models, my pets, are easier because they’re nude, I don’t have to pay them, and they’re always hanging around. When they sleep I think, “Oh my god, look at that shape. That’s very interesting.” I draw with the same pen I write with. It looks like my handwriting. The same line of my handwriting is the same line of the drawing. It’s curious.

Doyle: I’d love to turn to the topic of your writing process. In your essay “Hydra House,” your description of what it felt like to finish your novel The House on Mango Street enchanted me. You recount how you climbed on the wall between Hydra and Kaminia and “began to dance, feeling every bit the sorceress.” It seems like finishing The House on Mango Street was an ecstatic experience. Have you felt like this when finishing a work since?

Cisneros: That was the most memorable of all my books because it was like giving birth to a child, I imagine. I’ve never given birth, but it was like that. It was really something I wanted to savor. When I finished Caramelo, it was a different labor. Each one is different. Caramelo was a breached baby, so there was more relief.

Doyle: What do you mean by “Caramelo was a breached baby”?

Cisneros: I mean that I had the ending but not the beginning. I had it all backward. It was a very strange process, and I was lost most of the time. Whereas with The House on Mango Street, I wasn’t lost. I also knew when I was coming near the end. I just felt it. It was building. Whereas with other books, it hasn’t been that easy.

Each book is different. Each book has its own euphoria and its own celebration, its own labor and its own release. So, I never felt anything like I felt finishing The House on Mango Street on that Greek island. You have to remember, I had a house, I was living on an island. It was like a movie. I was twenty-eight years old. I had all these boyfriends. I was very popular. I looked very good, I must say. I had a great time. Plus, I didn’t need them. They could come, they could go. They didn’t torment me. It was so nice. I was in this wonderful state of being at that time. And then with the other books, there was death, there were heartbreaks, there were the tormentors. Each book is a different time in your life.

Doyle: Has your relationship to your books changed as your spiritual life has changed?

Cisneros: Yes. You know, I feel right now at sixty-seven a sense of gratitude for House that I didn’t feel ten years ago. I was kind of tired of House ten years ago. Whereas now I feel a sense of gratitude that this has given me so much protection and support for my other projects. Now I’m reworking it as an opera, so I’m seeing things in it I didn’t see before, and I’m getting to plunge into and develop characters in a way I didn’t when I was in my twenties.

I’m very proud of what I did. I wasn’t always proud when I was younger, but now when I look at House, I’m pretty impressed and think, “Wow, you did good!” And I just feel this astonishment that I was able to write that book from twenty-two to twenty-eight. I was so young, but I was working from a very intuitive and spiritual place. And by that I mean I wasn’t writing it to be famous or to win awards or to impress anyone. I think that’s essential, that we work from a place of service to others, with love. When you write from a place of service and love, your ego gets out of the way. It’s not about you. It’s about rescuing those you love and telling their stories with purity. It taught me a lot. The real way to be successful—in the way that I define success—is to write from a place of pure love.

The real way to be successful—in the way that I define success—is to write from a place of pure love.

Doyle: I’m so curious about that phrase, “rescuing those you love.” What does that mean?

Cisneros: I write about people whose lives are on fire. If you think of people you love who are living in houses on fire, would you run in and save them? Yes, you would risk your own being. So, I think about people whose lives are on fire. Maybe you know them so well. Maybe you lived in that house once. You think nothing of running in there and saving them. And that’s what’s on your mind.

Doyle: You’ve already mentioned a new book of essays that you’re working on as well as a libretto. If you’re open to continue discussing it, I’d love to hear more about what you’re working on now.

Cisneros: Yes, I’m still writing poetry. I have a new book of poetry that I concluded last August. It’s called Woman Without Shame. That’ll be out in September of this year. I also have a new translation of The House on Mango Street that the novelist Fernanda Melchor worked on. It just came out in the US, Mexico, and Spain. And my most recent book is Martita, I Remember You / Martita, te recuerdo. I’m looking for actors to help me present it here in Mexico in a readers’ theater. I’m involved in directing a little snippet, just a little book presentation. I’m doing a lot of Zooms in this time of Covid, and I’m going to be traveling again and doing some in-person events this spring. Once I become “the author,” then the writing shrinks. I envy friends who can write in planes and hotel rooms. No, I need my dogs.

I envy friends who can write in planes and hotel rooms. No, I need my dogs.

Doyle: Thank you so much.

Cisneros: Thank you. For what it’s worth to young writers out there, I never thought I’d be in this place getting these accolades and readers at this age. I didn’t have that on my agenda. I had much humbler aspirations. All of you that are out there working away, stick with it. It’s very important that you understand it’s not a sprint, it’s a marathon. Especially for women writers, read writers who make you want to write.

February 2022

Sandra Cisneros is the recipient of numerous awards, including the National Medal of Arts, the PEN/Nabokov Award for Achievement in International Literature, and fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and the MacArthur Foundation. Cisneros is the author of two novels, The House on Mango Street and Caramelo; a collection of short stories, Woman Hollering Creek; two books of poetry, My Wicked Ways and Loose Woman; a children’s book, Hairs/Pelitos; a selected anthology of her own work, Vintage Cisneros; a fable for adults, with Ester Hernández, Have You Seen Marie?; a memoir, A House of My Own; and a bilingual story that she also illustrated, Puro Amor. Her most recent book, Martita, I Remember You / Martita, te recuerdo, a story in English and Spanish, was published in 2021. This fall, her new collection of poetry, Woman Without Shame, will be published in English by Knopf and in Spanish by Vintage Español. Cisneros is a dual citizen of the United States and Mexico and makes her living by her pen.