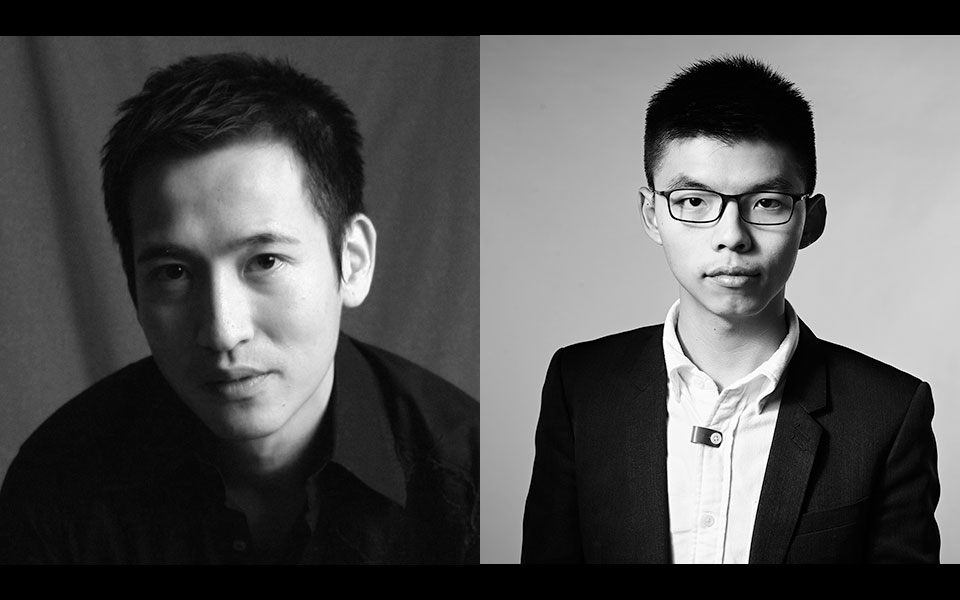

Hope Is the Most Powerful Arrow: A Conversation with Joshua Wong and Jason Y. Ng

In 2012, at sixteen years old, Joshua Wong and the pro-democracy student group he founded took on the Hong Kong government, mobilized more than one hundred thousand student protesters, and surprised the world by successfully convincing leaders to scrap a new Communist-sponsored curriculum. At seventeen, Wong helped lead pro-democracy protests that occupied Central Hong Kong for seventy-nine tear-gas-soaked days, earning him a Pulitzer Peace Prize nomination, two stints in jail, the cover of Time magazine, and a Netflix documentary—Joshua: Teenager vs. Superpower. Now, in his newly released book, Unfree Speech: The Threat to Global Democracy and Why We Must Act Now, Wong implores international audiences to fight tyranny before it’s too late. He was joined in writing the book by fellow activist Jason Y. Ng, a lawyer, newspaper columnist, and author whose own book, Umbrellas in Bloom: Hong Kong’s Occupy Movement Uncovered, depicts earlier waves of protest and the political fault lines that have led to the current crisis. The three of us corresponded over email to talk writing, the threats posed by growing authoritarianism, why hope is our strongest defense, and why the people of Hong Kong—who have much to teach the world about the spirit of community—are the real story.

Tiffany Hawk: Your just-released book, Unfree Speech: The Threat to Global Democracy and Why We Must Act Now, is part memoir and part manifesto. Where did the idea for this book come from? And why now?

Joshua Wong: The book was part of my contemplation when I was in jail. Speech is never free in a place under authoritarian rule, especially when you face imprisonment and deprivation of your political rights for defying unjust laws and orders.

However, tremendous changes have taken place since I was released. Before the outbreak in June, it was mainly movement leaders like Alex Chow, Nathan Law, and I who were put into jail, but now even a twelve-year-old kid was arrested, and ordinary people are sentenced to imprisonment just because they are accused of taking part in unlawful assemblies. When Beijing is tightening its grip on Hong Kong, Hongkongers have to pay a heavier price for a brief taste of freedom.

Speech is never free in a place under authoritarian rule.—Joshua Wong

Hawk: Jason, you’re a fellow activist with a shared mission and an accomplished writer, so you acted as translator and co-author of this book. What was it like writing together?

Jason Ng: The deadline given by Penguin was tight, and both of us had busy schedules, so we had to work efficiently and seamlessly. Fortunately, Joshua and I have been personal friends for many years, and I have been covering his career from the start in my news columns and books. Joshua also contributed to an anthology I co-edited for PEN Hong Kong. Few things need to be explained between us, and we “get” each other—that has allowed us to work together exceedingly well.

Hawk: Jason, when we first talked about doing this interview, I was going to ask if you ever worried about the potential consequences of publicly criticizing the government. Since then, a political tweet landed you in hot water with the international bank you worked for, and you’ve chosen to part ways rather than censor yourself. I’m sure that was one of the weightier decisions you’ve ever had to make. Are you open to talking about that decision-making process?

Ng: The decision-making was fairly straightforward and didn’t take me long. Everything in my training as a lawyer and my career as a writer and free-speech activist pointed to the same direction: I must stand up for what I believe in. I’m already much more fortunate than most people facing similar forms of attack and suppression: I have a second career—writing—to fall back on. My heart bleeds for those who aren’t as fortunate, like the Cathay Pacific pilots and flight attendants who lost their jobs for merely voicing support for the pro-democracy movement.

Hawk: Joshua, you’ve also faced consequences for speaking out—including a month in jail—but not only have you refused to quiet down, you now have a book being published in nine countries. Certainly you must sometimes feel afraid of what could happen to you. How do you overcome those fears and continue standing up for the cause?

Wong: Even though the imprisonment meant a lot to me, I did not shed tears or have any strong sense of fear when the judge announced my sentence in 2017. Rather than being brave, I viewed my imprisonment as the necessary step for the whole society to embrace the cruel fact that the city’s freedom is on shaky ground.

The days in prison also made me realize that the most fearful thing is not being put into jail but that ordinary life may one day look like prison if none of our generation dares to stand up for our civil liberties.

This feeling grows stronger, especially after police brutality has become ubiquitous. Without effective checks and balances, the police can arbitrarily abuse their power and torture citizens without consequences. Working with the police, mobs can just walk away after attacking pregnant ladies. Worse still, our government can be unanswerable to the demands of one-fourth of its population and keep repeating lies. What is fearful is when abnormality becomes normal and people get used to this Chinese-style “new normal.” Hence, our fight must continue so justice does not lose its shine.

The most fearful thing is not being put into jail but that ordinary life may one day look like prison if none of our generation dares to stand up for our civil liberties.—Joshua Wong

Hawk: In Jason’s book about the 79-day protest in 2014, Umbrellas in Bloom, he compares Hong Kong to a house with a gas leak. “All it takes for it to blow up is a single spark . . . but we can always count on it [the government] to do something spectacularly stupid. When that happens, citizens will once again put down their differences and come together, no matter how fractured and polarized they seem at the moment.” Were either of you surprised by the new round of protests that started last June?

Ng: I knew it was only a matter of time before another protest movement would hit the city, but I didn’t know it would happen so soon and so suddenly. Before last June, I had thought that Hongkongers were still suffering from protest fatigue and wanted to take a break from political wrangling, but I suppose I must have underestimated our tenacity and overestimated the government’s ability to keep out of trouble.

Wong: The protests that started last June are completely beyond every Hongkonger’s imagination. The movement has definitely triggered a series of paradigm shifts in the city’s pro-democracy movement. Right before that, Hong Kong protesters were still in the darkest valley. The failure of the Umbrella Movement dealt a devastating blow to the morale of activists. People felt disillusioned when newly elected lawmakers were unseated and protesters were sentenced to prison. But deep down, as I know, time heals all wounds. When the time comes, every Hongkonger will be ready to stand on the front line to defend the city and values that they love and cherish.

Hawk: Certainly with as many as two million citizens turning up for recent protests, you’re not that far off. Besides size, what’s the most striking difference between the Umbrella Movement protests and now?

Ng: To me, the biggest difference is how fluid the protests are these days. While the Umbrella Movement was predicated on the occupation of three key urban districts, the current protests are everywhere and can occur at any time. Protesters have taken Bruce Lee’s “Be Water” philosophy to heart and for good reason. To be “formless, and shapeless, like water” is the only way to outwit an opponent—the police force—that outnumbers and out-arms them.

Protesters have taken Bruce Lee’s “Be Water” philosophy to heart and for good reason. To be “formless, and shapeless, like water” is the only way to outwit an opponent—the police force—that outnumbers and out-arms them.—Jason Y. Ng

Wong: The main difference is the leaderless character. This unique organizational structure somehow empowers all the participants of the movement. As the movement is now decentralized, everyone can contribute to the movement with their creativity and resources. Professionals provide the frontline fighters with medical support, and small store owners supply demonstrators with free water and face masks. Teenagers formed barricades on the front line, while parents and the elderly stood guard on bridges. Deep down, we know, this time it’s a war on everyone, and also a war for everyone.

Hawk: That makes me wonder about your role as the democracy movement’s “poster boy,” if you will. For a time after my own book came out, the media turned to me as a go-to interview for airline stories, basically asking me to speak about various controversies on behalf of all flight attendants, which was a very weird experience. So Joshua, I’m wondering how you feel when the world media calls you the leader of the Hong Kong protest movement, even as they—and you, for that matter—characterize these protests as leaderless.

Wong: I share the same uneasy feeling, as the movement is different this time. In this leaderless movement, every single individual can act heroically. In the very beginning, dozens of activists sacrificed themselves to remind people of the evil nature of the bill. Students safeguarded the integrity of the university by defending the campus with their lives, while adults refused to leave student protesters behind, even though they knew that they could be sentenced to ten-year imprisonment. Walking with crutches, grannies stood up on the front line to protect protesters. Volunteer drivers rushed to rescue thousands of besieged protesters in the airport. All of them are the anonymous heroes who love this city and defend it with their bare hands.

Walking with crutches, grannies stood up on the front line to protect protesters. Volunteer drivers rushed to rescue thousands of besieged protesters in the airport. All of them are the anonymous heroes who love this city and defend it with their bare hands.—Joshua Wong

Hawk: You have both devoted so much of your lives to fighting for what you believe in. For those who may lack the resources or the time or the freedom to be as involved as they’d like to, how do you recommend they contribute to the fight for values like democracy and free speech?

Ng: If you have a family to support, work for the government, or deal regularly with mainland Chinese clients, you face more constraints than people like me and Joshua. But one thing about the fight for democracy is that there are a myriad of ways to contribute. Ordinary citizens can pitch in in whatever way they feel comfortable with or can afford to. At the most basic level, they can register as a voter and use their vote to hold people in public office to account. Merely by being politically engaged, paying attention to current affairs, and relaying the information to others—one friend or family member at a time—can make a big difference over time.

Wong: Just like all freedom fighters from other places in the world, we are standing up for values that we believe and pressing for institutional changes. The road is rocky, and people may face constraints and pressure.

This is where civil society comes in, providing support to each of the individuals. In the case of Hong Kong, many of the protesting teenagers grow up in conservative families, of which some will call police on their children or kick them out of their homes, simply because they have found gas masks in the children’s rucksacks. Luckily, social workers and religious groups in Hong Kong help provide shelters and counseling to this group of people. Therefore, for those who fight for democracy and freedom, my advice is that it is important to build up a robust and interconnected network to support our battle, be it legal, medical, financial, or even psychological. By standing together, there is nothing we cannot overcome.

Hawk: And in Unfree Speech, you do emphasize that this is a group effort, that it’s not just Hong Kong being threatened by authoritarianism, or even by China’s own brand of control. What else do you think the rest of the world should learn from Beijing’s approach in Hong Kong?

Wong: Hong Kong is the testing ground for Beijing’s infiltration into a society where people once enjoyed certain degrees of freedoms, including a free press, truth-searching reporters, free social media where people can express themselves, and a robust civil society.

But the Beijing government tightens its tyrannical rule on Hong Kong. Using China’s market as economic leverage, Beijing successfully makes the business sector succumb to its political redlines. With the help of its handpicked Hong Kong government, Beijing also imposes censorship in schools and media outlets to screen out political messages by pro-democracy activists and dissidents. Worse still, Beijing also expands its representatives in Hong Kong and sets up more pro-Beijing satellite organizations to groom antidemocracy voices, shape public opinion, and spread extreme nationalism in Hong Kong. In recent years, Beijing has started similar forms of political infiltration overseas, by setting up overseas pro-Beijing satellite groups and influencing the business sector with economic leverage.

Therefore, if the world fails to start paying attention to Hong Kong or to treat our story as the warning signal, the civil liberties in other countries will soon be in peril.

If the world fails to start paying attention to Hong Kong and treat our story as the warning signal, the civil liberties in other countries will soon be in peril.—Joshua Wong

Hawk: Remarkably, in 2012 you and Scholarism, the pro-democracy student group you founded, were able to galvanize so much opposition to the “Moral and National Education” curriculum that you successfully scuttled it. But then in 2014, neither the Hong Kong government nor Beijing conceded to any of the subsequent Umbrella Movement’s demands. Similarly, although the current uprising did ultimately succeed in stopping the controversial extradition law that first brought people to the streets, it seems unlikely China will address the protesters’ other key demands such as universal suffrage that was promised in the Basic Law, more or less Hong Kong’s constitution. Why is it important to wage this battle, even if you’re unlikely to get what you want?

Wong: Despair is one of the weapons that China uses to stem calls for change. After the recent death of the [Coronavirus] whistleblower Doctor Li Wenliang, anger raged across social media, but in an intense color of hopelessness. People have little hope for the Beijing government to make reforms. Applying the same “despair” model when governing the city, the Beijing government tries every means to answer the people’s demands. It is thought that they can turn Hongkongers into docile and cynical people. Luckily, the protests last year show that such a model does not work here.

That is the reason why the battle must be carried on as we must rescue our city from falling into despair. What matters is not just the goals that we want to achieve but the whole process through which the civil society strengthens its fiber. Only with hope, we protest, and only with hope, we yearn for change.

Hawk: It sounds like, despite everything, you both feel hope for the future of Hong Kong and for the future of democracy around the world.

Ng: Hope is the most powerful arrow in our quiver, and we must keep it sharp. Even if the odds are stacked against us, we owe it to ourselves and our future generations to at least try—because not trying at all is exactly what the authorities want us to do. Apathy and hopelessness are the most certain way for those in power to beat us. I believe as long as we stand together united, the arc of history will eventually bend toward us.

Apathy and hopelessness are the most certain way for those in power to beat us. I believe as long as we stand together united, the arc of history will eventually bend toward us.—Jason Y. Ng

Wong: I have confidence in Hongkongers, but I also point to the fact that Hong Kong is on the brink of a crackdown by Beijing. Beijing fears all democratic aspirations on its territory and makes every effort to nip them in the bud. Threats of suppression loom when many signs show that the Beijing government will start tightening its reins on Hong Kong. Weeks ago, Beijing just appointed the party’s hardliner, Xia Baolong, as the new head of the Hong Kong and Macau Affairs Office. Xia was well known for burning crosses and demolishing churches in China during his tenure in the eastern province of China. The CCP’s top leaders announced they will “strengthen laws and enforcement mechanisms” to tackle the political crisis in Hong Kong. It is a matter of time until further suppression is put in place.

As Hong Kong is the forefront of the free world to stem the authoritarian expansion of China, I hope the world can stand with Hong Kong in the new year. Only when we stand together can we have a chance to win this war against tyranny.

February 2020

Editorial note: WLT’s spring 2019 Hong Kong issue, guest-edited by Tammy Lai-Ming Ho, is a great place to learn more about the city—for starters, check out Xu Xi’s recommended booklist.