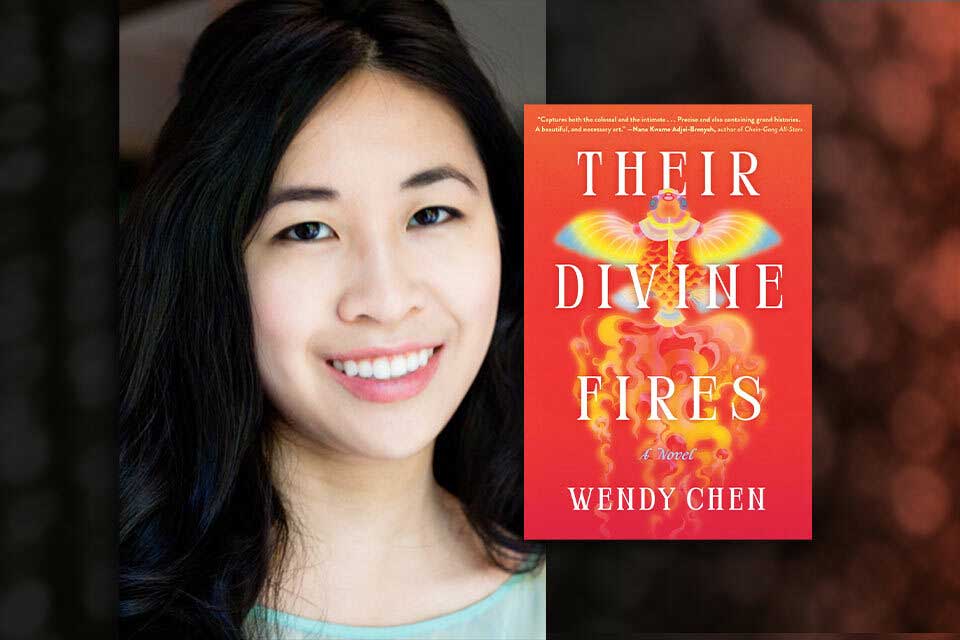

Can We Truly Be Free of Our Past? A Conversation with Wendy Chen

An epic family saga that spans over one hundred years and two countries, Wendy Chen’s powerful, lyrical debut, Their Divine Fires (Algonquin, forthcoming on May 7, 2024), is about history, love, passion, loyalty, betrayal, and our desire to be free of our past. In the novel, four generations of women survived the formidable hardship in China during the tumultuous twentieth century—the warlord melee, the Communist–Nationalist civil war, the Japanese invasion, and the Cultural Revolution—each emerging with unspeakable loss and heartache yet undampened spirit for life and the future. An intimate study of family relationships with the backdrop of a chaotic, changing world, this book provides a perspective on Chinese history rarely seen in American literature.

An epic family saga that spans over one hundred years and two countries, Wendy Chen’s powerful, lyrical debut, Their Divine Fires (Algonquin, forthcoming on May 7, 2024), is about history, love, passion, loyalty, betrayal, and our desire to be free of our past. In the novel, four generations of women survived the formidable hardship in China during the tumultuous twentieth century—the warlord melee, the Communist–Nationalist civil war, the Japanese invasion, and the Cultural Revolution—each emerging with unspeakable loss and heartache yet undampened spirit for life and the future. An intimate study of family relationships with the backdrop of a chaotic, changing world, this book provides a perspective on Chinese history rarely seen in American literature.

Xixuan Collins: You capture the emotions of the four generations of Chinese and Chinese American women so vividly. You have said that you were inspired by your grandmother’s stories of her mother and uncles and the ways they fought, lived, and died for what they believed in. Can you tell us a little more about the story behind your story; that is, what was the moment when you realized you had a story to tell and you felt compelled to sit down and write this novel?

Wendy Chen: My grandmother would always tell me stories of her family when I was little. They would be stories about her mother, who refused to bind her feet, as well as stories about her uncles, who were Communist revolutionaries in the early 1900s. Though I was too young to understand the historical and political context behind her stories of revolution, they were basically bedtime stories for me. She always asked me to write them down someday in order to preserve them. My family doesn’t have many records or heirlooms—much of it having been lost in the last century of revolution, civil war, and war in China. These oral histories and memories are all we have by way of keeping the past alive.

After I published my first collection of poetry and turned to fiction, I knew I wanted my first novel to pay homage to my grandmother’s stories and the history of my family. It’s always been a wish of mine to publish this novel while my grandmother was still alive. That, happily, was able to come true. She’s in her midnineties this year and was able to hold an advance copy of the novel in her hands a few months ago.

Collins: That’s so fantastic! I’m so glad to hear that! She must be so proud of you. As you mentioned, before you became a novelist, you were a poet. Your poetic language is so beautifully displayed throughout this book. Here’s one example: “Sitting beneath the stars, Mei Mei felt as if she were borrowing their light, every part inside her aglow.” So gorgeous. How does being a poet shape your use of language? What’s something you learned about writing a novel? What surprised you? What was the most difficult? What was the most fun? How do you balance crafting beautiful sentences with moving the story forward? Let’s face it, many readers just want the story!

Chen: Thank you so much for your kind words about the language in the novel! Poetry taught me how to craft and shape the line. When I started writing a novel, I had to learn how to craft and shape those lines into a story. Writing this first novel was very much a learning process for me. That’s probably why this novel took almost a decade from start to finish—which was certainly a surprise.

I’ve gone through countless revisions with this novel and done major overhauls. I probably had three very different drafts in total before I was able to land on the final shape of the novel. My early drafts were focused on the movement of the line, and the story emerged out of that movement of the line.

Revision was the most difficult—and important—part of the process. I had to cut lines that were beautiful but didn’t serve the momentum of the story, and also write lines that would push the momentum forward. Before, as a poet, I was more used to writing toward an emotional logic, rather than a narrative one. That all changed with a novel!

Learning how to strike that balance between the line and the story is certainly challenging. Outlining and reverse outlining my later drafts helped me in revision. I’m unable to outline early drafts, however, as I need the excitement of the line to push me forward and keep me interested in writing. Reading and rereading favorite novels was also incredibly helpful as well in learning how to strike that balance.

Collins: Outline later drafts, but not early ones—so interesting. I love your insight about focusing on the movement of the line first and then letting the story emerge. It must be hard to cut beautiful lines. None of us want to kill our darlings! You did such a great job of keeping the story moving through your beautiful lines. One example is the naming of your characters. I love the names, and I tried to write the Chinese characters next to the names in the family tree. The names said so much about their times and relationships. For example, the three Zhang siblings: they were just Da Ge, Ge Ge, and Mei Mei when they were still connected because of their shared blood, and then they became Yunli, Yunjun, and Yunhong after they were forced (or chose) to sever their ties because of what happened.

And the names given to children in the 1950s and ’60s! Leap Forward, Resist America, 716, in addition to Forever Red and Love of Your Country: all of them remind me of people I knew as a child growing up in China in the 1970s. And then, of course, Forever Red (Yonghong) became May, and Love of Your Country (Aiguo) became Jack when they moved to the US. How did you decide their names? Why is it so important to have these names? Do you have any worries that readers may complain about the hard-to-pronounce names and names with a same character (Yunhong, Yonghong, Hongxing, and Hongmei) they may find confusing?

Chen: I’m so glad you enjoyed the names in this novel! I had the most fun with naming characters who were born during the time of the Cultural Revolution, as many of them are imbued with the political fervor of the time. Chinese names are also so rich, varied, and often reflective of a particular time period. There is an art and poetry to them. When I was choosing names for the characters, I wanted the names to have an emotional resonance to the characters and the story. I did lots of research into popular names of each era and worked my way from there.

For Yunli, Yunjun, and Yunhong, I wanted them all to share the same character in their names—“yun”—to mark them as siblings. As I’m sure you know, this is a naming convention that is not uncommon in China; in fact, my sister and I share the same character in our names. The shared character in the three characters’ names marks their closeness with one another and, later, is a reminder and representation of what they’ve lost over time.

Anytime a writer chooses non-“American” names, inevitably someone may complain about that choice making the reading experience more challenging. Ultimately, I’m not interested in whitewashing my work for that kind of audience. What’s more, where would one draw the line in terms of making such changes to appease those readers? I welcome readers who are unfamiliar with the history, names, and kinds of characters I write about; indeed, I hope that my writing can help them outside their comfort zones in terms of what they are used to encountering in their daily lives and in their reading practices. As a reader, some of my favorite books are ones that do just that—expand my understanding and imagination about the world even if the material itself is unfamiliar or challenging.

Collins: So true! My father and all his siblings also share the same middle character of their names. And, “I’m not interested in whitewashing my work for that kind of audience.” Bravo! Speaking of hard-to-pronounce words, I’m so glad to see that you used pinyin words such as weiqi, qilin, Leigong, and Dianmu in your book like they are normal words, without italicizing them. When I read a book that has Scottish slang, I look them up. I think readers should do the same when they read pinyin. Was it an easy decision to make, using these words as they are?

Chen: A decade ago, when I first started seriously publishing my work, the literary world was still debating whether one should even include foreign words in one’s writing without translating them. If a writer did buck against expectations, the expectation was that they italicize those words. Now, for writers of color, it is far more common to include different kinds of Englishes and languages in one’s work. Many of us have also chosen not to italicize foreign words in our work, as the italics can emphasize a sense of otherness.

There were certain words I wanted to include as pinyin to highlight a richness of history, culture, and reference points without creating that sense of otherness. Take qilin, for example, which is a mythical beast in Chinese culture. I have seen qilin translated as “Chinese unicorn,” but I find that translation inaccurate and unwieldy. Indeed, if I were a reader who came across “Chinese unicorn” instead of qilin, I would find that somewhat patronizing—as though I don’t have the capability to understand or imagine beyond a Eurocentric reference point.

Collins: Such a great point! I remember debating about “gan-daughter” in my novel and decided to leave it rather than translating it to “goddaughter” because they really are not the same things. The story of Leigong and Dianmu is one of the many Chinese stories or fairy tales you told in your book. I particularly love the three stories Ge Ge told Yuexin—I have a special tender spot for Ge Ge because I played erhu as a child (I regret to say I don’t anymore)—that are the metaphor of their lives. Also, the stories of the dragon and the tiger.

What research did you do to include these stories? What do you think fairy tales tell us about a country and its people? What exactly is the “dragon” that all Chinese people seem to claim? Is it good or evil? If it’s evil, maybe we can use the world “dragon,” since in the Western tradition dragons are fire-blowing monsters. If it’s the benevolent protector of China and its people, maybe we should use the pinyin word “long”? Just like qilin, not “Chinese unicorn.” What are your thoughts?

Chen: I always wanted to learn how to play erhu, as it’s been described as the instrument that’s the closest to the human voice. I was interested in framing the erhu as a metaphor for storytelling, so the chapter where Ge Ge tells his three stories came very naturally to the writing. I read a lot of Chinese fairy tales as a child and grew up watching Journey to the West in the 1990s, so drawing on those memories provided me with the inspiration for the more mythological stories in the novel.

In Journey to the West, for example, the fantastical encounters and mythical beasts reflect religious and moral debates of that time. In my own novel, I was interested in incorporating myths and fairy tales as a form of metareflection on the narrative and historical period.

The long or dragon in Chinese culture is such a weighted symbol. For many centuries, the dragon was associated with the emperor and thus a sacred and untouchable image. After the fall of the Qing dynasty, China had to reconceptualize its relationship to the dragon and to itself as a nation. My novel is about what happens during this time, after the last emperor. Thus, I wanted to represent a dragon that is neither good nor evil, but a representation of the larger historical forces that shape the lives of my characters. The dragon appears remote and removed from human matters but is actually ever-present and watching.

Collins: So well said! One fairy-tale aspect of your novel is the red birthmark on the chest shared by the four generations of women in this family. The birthmarks burn when they fall in love. It’s a scar, also a curse. Interestingly, Hongmei, who is not related to the women by blood but by love, at least for a while, also bears a birthmark, only it’s on her ankle. What is the significance of these birthmarks? What inspired you to make the birthmark a central image of this novel?

Chen: I’ve always been fascinated by birthmarks, being born with several of them. I have a birthmark on the sole of my foot that my grandmother always used to say was a way for her to find me if we were ever separated. I’m interested in the ways that birthmarks can tie us together—as a symbol of familial bonds, inheritance, or love. The birthmarks evolve and change with the women in the family as they experience pain, grief, sadness, love—but also serve as a reminder of what they’ve left behind and what they will always be a part of.

I’m interested in the ways that birthmarks can tie us together—as a symbol of familial bonds, inheritance, or love.

Collins: In your book, there are stories of grandmothers, but for the most part, both the women and men are young. Your book does a fantastic job of presenting, so truthfully, a picture of Chinese youth throughout the twentieth century, why they fought the revolution, over and over again, and the history of the Communists and Nationalists. They believed that they were fighting “for the soul of China” and that “all things worth having come at a cost.” They strived for a world where “the rich will walk with the poor as brothers, the land shared freely by all.” Both Da Ge and Ge Ge went to First Normal School in Changsha, the same school attended by Mao Zedong.

Why do you think it’s important to share this history with American readers? It didn’t escape me that the fervor of the MAGA crowd is comparable to that of the Cultural Revolution youth, as observed by Yonghong and Hongxing. Isn’t it ironic there exists such a similarity between the capitalist and the communist crowds? I think Viet Thanh Nguyen said something about communism and capitalism having more things in common than we might think. . . . Is it dangerous for a society to pursue one single ideology, no matter how noble it may sound or seem, with a zeal that deems all other ideas inferior or unacceptable? What can we do to learn lessons from our past?

Chen: I’m so glad that you feel I’ve captured the energy, idealism, and fervor of the youth! Yes, another important reason why I wanted to write about China and one particular family’s story over the last century was to humanize the individuals and histories who shaped China to what it has become today. Growing up, in history classes and popular media, China and communism was always framed to me as the opposite of America and democracy. The reality, of course, is much more complicated. I very much agree with what Nguyen observes about the commonalities between the two and am also struck by how quickly political fervor can enflame a group of people, oftentimes to the detriment of whoever is deemed an “enemy” or “other.” Hope and idealism can lead to so much good but also so much violence, pain, and hatred. There’s the age-old adage of learning history so as to not repeat it, but I feel we are doomed to repeat history either way. Rather, I think an important lesson to take from looking at the past is compassion, rather than judgment.

There’s the age-old adage of learning history so as to not repeat it, but I feel we are doomed to repeat history either way.

Collins: This is why we need books about history, and we need fiction. Research has shown that reading fiction allows us to have more empathy and compassion for others. The backdrop of your book is the Chinese history of the twentieth century, and with this backdrop you conducted intimate studies of family and love. Like all of us, the characters—I call them “characters” for lack of a better term, because they are real people to me—long for everlasting love. But in reality, the true loves, the romantic kind, anyway, were all so fleeting. I’m talking about Yunhong and Haiyang, Ge Ge and the Communist woman, Shengming and Miss Wu, Yonghong and Leap Forward, and Hongxing and Hongmei. Why is that? Do you believe in everlasting love? Is it possible to achieve everlasting love when one’s entire fate is not within one’s own control?

Chen: Surely, a prerequisite to becoming a poet is believing in everlasting love? Jokes aside, I’m interested in the ways that love can shape and change us even if we don’t end up staying together and having the typical “happy ending.” The greater the turmoil and instability of the time, the more difficult it may be to love one another—openly and honestly. I’m thinking of the Cultural Revolution, for example, when it was not uncommon for family members to denounce one another as counterrevolutionary. And yet, that is perhaps what is most inspiring to me—that we can come together—even if only for a brief time—and love another despite it all.

I’m interested in the ways that love can shape and change us even if we don’t end up staying together and having the typical “happy ending.”

Collins: Someone once said, “You always get more respect when you don’t have a happy ending.” You have certainly earned my respect! Joking aside, I have a craft question. Your book seems very familiar to me in the sense that you’re telling a story much like the Chinese novels I read growing up and am reading now—think about Mo Yan’s Life and Death Are Wearing Me Out and Yu Hua’s To Live—and the work I’m trying to produce. You’re telling the story of a family, how they lived, died, loved, hated, suffered, and rejoiced. There’s not the typical “stake” that is so crucial for a typical “American” novel, although I argue that the desire to live is the highest stake. The book doesn’t fit neatly in a five-part or seven-part story structure.

I’m sensitive to this because my own manuscripts have been criticized as such. For a while, I had been discouraged about my writing, until I read Matthew Salesses’s book Craft in the Real World. In this book, Salesses has an excellent chapter on East Asian and Asian American literature, in which he explained the model of traditional Chinese fiction, such as: “Telling had priority over showing” (gasp!) and “The plot structure . . . does not require conflict” (another gasp!), etc. I’m so excited about the publication of your novel, not only because it’s such a great book but also because it gives me hope that literary fiction like yours is accepted and celebrated by the publishing industry. What are your thoughts on this? You’re also a translator, and I think you probably understand very well the importance of reading non-Western work.

Chen: I reread quite a bit of Mo Yan, Salman Rushdie, Gabriel García Márquez, and Toni Morrison while writing this novel, so I’m glad you picked up on some of the influences! I have also taught excerpts from Craft in the Real World in my undergraduate classes, as I find clear and compelling the way Salesses lays out different story structures and workshop models. I’ve had students come up to me after class saying that they’ve never thought about alternative story structures before and how story structures shape the way we think. That alone is evidence of the importance of reading widely and outside of our own comfort zones.

Though there was quite a learning curve for me in terms of writing a novel as a poet, there were some benefits as well. One being that I really didn’t have any idea how to write a novel in the beginning. This freed me up from feeling like I had to shoehorn my novel into a five-act or seven-act story structure. Rather, I learned how to write a novel from the novels I loved to read, which were usually emotionally intense literary texts with a particular intensity and focus on the line level. I also learned how to write from the fiction professors at my MFA program in Syracuse—Dana Spiotta, Mary Karr, George Saunders, Arthur Flowers, Jonathan Dee, Jenny Offill (who was a visiting professor one year). All of them introduced me to a variety of different texts and encouraged us to explore, experiment, and fail boldly with craft.

And one other aspect that can’t be stressed enough: the importance of having a supportive network of friends who are also writers and trusted readers of your work. The greatest gift an editor or reader can give you is evaluating your work on its own terms, rather than against what they personally like or don’t like in writing. Having a supportive writing community has sustained me as a writer and allowed me to keep writing all these years.

Collins: Such good advice for writers! I’m envious that you have studied with such luminaries! I’m also encouraged that you think one of the best ways to learn how to write is to read widely, to learn from the novels we love. Also, the importance of a supportive writing community is so true.

I wish we could continue this conversation forever, but all good things must come to an end. My last question is about the desire to be free of our past. Your characters have done all kinds of things trying just that: Da Ge has his long Manchurian braid cut; Yunhong cuts her own hair; Yunhong does not admit Yuexin as her daughter; Yunhong signs papers on her parents’ behalf to disown her brothers; Hongmei dances to be free; Yonghong moves across the ocean; Yunhong fails to cut Yuexin’s birthmark, but Emily succeeds in having her own birthmark cut. Can we really be free from our past? If so, how can we achieve that? If not, how do we continue to move forward?

Chen: This is such an important question to me personally—one I’ve always wondered about. Part of my own anxiety around that question stemmed from feeling the weight of all my family stories—and wondering what I was supposed to do with all the grief, regret, love, hope, faith, all those individual choices, feelings, and thoughts that led, eventually, to my existence. Through my own experiences and observations of my parents’ generation, I’ve come to the conclusion that trying to entirely erase or forget about the past often can lead to a state of denial and paralysis. Rather, accepting the fact that the past will always be a part of us is powerful. Acknowledging the ways the past has shaped our lives and perspectives helps us move forward.

Collins: Wonderful! Let their and our divine fires burn. Thank you for this wonderful conversation. What an honor.

March 2024