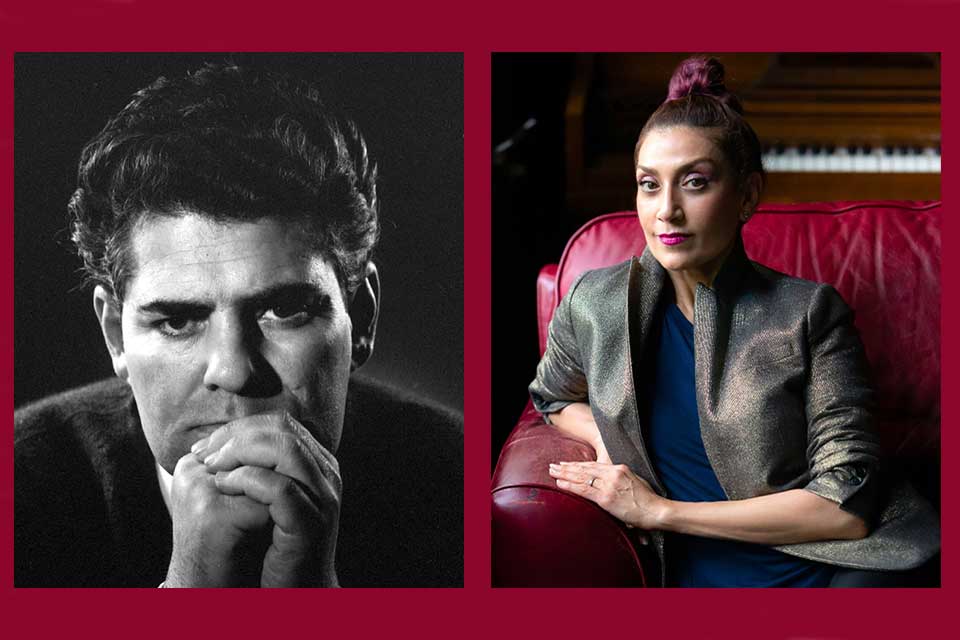

Ahmad Shamlou on the World Stage: A Conversation with Niloufar Talebi

In Self-Portrait in Bloom, Niloufar Talebi (www.niloufartalebi.com) tells her story of growing up with Iranian poet Ahmad Shamlou, both the man whom she knew personally, and his outsized cultural legacy as it has figured prominently in her own artistic career. The book offers English readers a new look at Shamlou via Talebi’s original translations of his poetry and her studied discussions of his writing, thought, and cultural milieu. At the same time, Talebi recounts her experiences coming of age in Iran and California and the struggles and triumphs that she has faced as an artist working in multiple genres. Self-Portrait in Bloom ultimately raises powerful questions about what it means to make art and the sacrifices that one makes to live the life of an artist. In this interview, Talebi discusses her new book with Samad Alavi, senior lecturer in Persian at the University of Oslo.

Samad Alavi: Self-Portrait in Bloom reads in many ways like several books in one. It is a portrait of you as an artist and translator and at the same time a portrait of the Iranian poet and cultural giant Ahmad Shamlou. So it is a memoir of sorts and also an artistic study of Shamlou’s work. And it is a reflection on translation as craft. Then of course there are your original translations of Shamlou’s poetry, which form the heart of the book. So, to get started, how would you describe Self Portrait in Bloom? Were there other books that inspired you to write in this memoir / artistic study / translation form?

Samad Alavi: Self-Portrait in Bloom reads in many ways like several books in one. It is a portrait of you as an artist and translator and at the same time a portrait of the Iranian poet and cultural giant Ahmad Shamlou. So it is a memoir of sorts and also an artistic study of Shamlou’s work. And it is a reflection on translation as craft. Then of course there are your original translations of Shamlou’s poetry, which form the heart of the book. So, to get started, how would you describe Self Portrait in Bloom? Were there other books that inspired you to write in this memoir / artistic study / translation form?

Niloufar Talebi: I searched for a term to describe how I studied Shamlou. I knew I did not want to venture a complete biography, but what is done here is more than an introduction. So I chose “portrait” to describe it. I did years of research, reading anything I could find, scholarly articles, including your well-written dissertation on Shamlou and his commitment. I am an artist, and so all that information, and my own firsthand familiarity with Shamlou, along with my projection onto him what an artist yearns to accomplish in the world, all together created the approach that became Self-Portrait in Bloom, my way of bringing Shamlou to the attention of a wider, global audience. To take things further, I also conceived Abraham in Flames, an opera inspired by Shamlou’s life and the striking imagery in his work. So my project of sharing Shamlou with the world spans multiple mediums and projects.

I am an artist, and so all that information, and my own firsthand familiarity with Shamlou, along with my projection onto him what an artist yearns to accomplish in the world, all together created the approach that became Self-Portrait in Bloom, my way of bringing Shamlou to the attention of a wider, global audience.

How would I describe Self Portrait in Bloom? A combination memoir, portrait, essay, poetry, poetry in translation, and photo essay.

And as to whether there were other books that inspired me to write “in this memoir / artistic study / translation form”? Yes and no: I love and read hybrid books, but I have yet to read one that combined these specific elements and genres together, though such a book may exist somewhere. I had no idea how I was going to say everything I wanted to say and try what I really wanted to do, which was fitting more than one book in a book. It was tricky to map out the constellation, figure out the structure, and weave all the disparate elements together so that it all built toward something without losing the book’s threads. I wrote for years and compiled over half a million words knowing it would be pared down and reimagined into a 50,000-word book. In the last year of work, 2018, I was lost in a dark tunnel as I kept adding more research, staring at and pushing sentences around, and deleting sections that no longer worked in the moving target of the mystery creature that was staring back at me. Thankfully, the structure and possibilities of the book began to emerge during my intense one-month work with my editor, Chris Abani, whose own multigenre work made him the perfect fit for my dream for this book. I will never forget the miraculous day when I rearranged some sections at the end of the work session and realized they were chapters!

Alavi: The book captures your ease working across genres and drawing from all kinds of artistic forms very well. There are references to literature (of all kinds), painting, music, dance, drama, opera, and so on running all throughout the book. We get to hear this really rich dialogue between you, Shamlou, and world art, which I think is especially appropriate for Shamlou’s vision and legacy, not to mention your own. Considering how profoundly Shamlou regarded himself as a voice of world literature, why hasn’t his poetry become more visible in the English-speaking world?

Shamlou devoured the world whole; he loved all people and the cultures they make, and stood against what is diametrically opposed to that—oppression.

Talebi: Yes, Shamlou devoured the world whole; he loved all people and the cultures they make, and stood against what is diametrically opposed to that—oppression. His orientation was expansive. The education I received, both at home and through my own curiosities, was and continues to be similarly multidisciplinary, which fuels my point of view and artistic output.

As to why Shamlou’s work has not become more visible in the English-speaking world? I try to address that question in Self-Portrait in Bloom: it is a combination of translations unsuccessful in rendering the linguistic complexity and innovations in Shamlou’s work or adequately introducing the cultural and political contexts in which Shamlou created art, an oppressive Iranian government that censors its artists and hinders their legacies, the country’s problematic position on the world stage, ideologies and sanctions that directly translate into an absence of cultural exchanges, and other factors such as the one I describe in the latter part of Self-Portrait in Bloom.

Alavi: The factors that you describe in the latter part of the book are, to put it mildly, pretty unbelievable. I imagine that many readers will think of censorship as something that only happens in “oppressive” countries, but what you describe is a type of censorship, silencing, and bullying that funders and publishers in the United States were either powerless or unwilling to prevent. Do you want to get into the details of your experiences here or leave them for readers to discover in the book?

Talebi: It took me years to be able to tell that story. I wrote it dozens of times, each time halting somewhere in the middle, simply because I could not find the words, baffled, incredulous that my life had come to that. My brain and heart could not compute what I consider an act of violence, a stripping of hope, dignity, not to mention all the tangible—and, still greater, intangible—damages it inflicted and continues to inflict. I think I will let readers discover it on their own.

Alavi: I really enjoyed reading about how you revisited and reconstructed your childhood home, Tehran, via the internet. How does something like Google Maps change the way we remember a place? What role does the internet play in contemporary memoir writing or, if you care to wax philosophic, in memory itself?

I was trying to build a 3D world from shaky memories and maps, a world I could feel, smell, walk through, all the while knowing that our minds rewrite, replace, and overwrite our own stories.

Talebi: I wonder how many writers stalk their own past the way I did. I became possessed once I opened the Google Maps floodgates. I did not answer any calls and would sometimes research until 6:30am. I was asking strange questions of my father about the trees that lined certain streets whose names that I did not even remember. I was trying to build a 3D world from shaky memories and maps, a world I could feel, smell, walk through, all the while knowing that our minds rewrite, replace, and overwrite our own stories, hence the total unreliability of who we think we are, exciting in a way because of the possibilities of reinvention.

Alavi: What was a difficult line, passage, or poem to translate with whose results you are especially satisfied? Can you talk us through the translation process? What was difficult about that selection, and how did you work it into an English form that met your satisfaction?

Talebi: Shamlou’s genius was in synthesizing, referencing, and connecting elements from both the Western and Eastern canons within one work, making imaginative and imagistic leaps that require fluency in both traditions. “Hamlet,” one of my top 10 favorite poems of Shamlou, was particularly challenging and endlessly satisfying to translate. There are multiple references to curtains, half-faded or not, and because curtains appear so often in Shakespeare’s play, literal and metaphorical ones, I had to decipher which curtain was being referred to so that I could decide how to translate the material around the references. I spent time rereading and researching the play in the concentrated time I had to complete all the translations. All the while, I had to be sure to carry the poem that lay between the first question and the last one through as one thought—Shamlou’s version of the famous soliloquy.

Alavi: What other writer or book would you like to see translated from the Persian?

Talebi: What I wish for is a more even exchange between Iranian writers and non-Iranian ones. I would hope the dialogue would engender cross-breeding, translation, and literary innovation.

Alavi: Where will your work on and conversation with Shamlou take you next? Will your translations play a part in future performances?

Talebi: I describe in Self-Portrait in Bloom the opera project I created inspired by Shamlou—even despite the monumental obstacles presented to me. It is called Abraham in Flames, titled after Shamlou’s seminal 1974 book of poems, Abraham in Flames. The opera world-premieres on May 9–12, 2019, in San Francisco. I love how the opera transformed as a result of those obstacles to become a coming-of-age story, a work written for a girls chorus as its main character, Girl. I think of Self-Portrait in Bloom and Abraham in Flames as twin expressions of the same impulse, to make Shamlou visible on the world stage.

Alavi: One question just for fun: you are an artist conversant with many different forms. Can you recommend a playlist to listen to while reading the book? What five recordings or albums would you recommend to accompany a reading of Self-Portrait in Bloom?

Talebi: Oh, I have more than five to add to those listed in the book. Here are some of the works I was listening to during the events of these chapters:

Chapters 1, 4, 6: ABBA, Bee Gees, John Lennon, Schubert’s “Ave Maria,” Boccherini’s minuet for string quintet, Rush, and when my father is on the page, Shajarian, Banan, old Iranian art songs by Delkash, Viguen, and Elaheh.

Chapter 7: Bach’s keyboard concerti, Michael Jackson’s “Thriller” and “Billie Jean,” 1980s music, the Cure, Tears for Fears, New Order, Wham!, Prince, Depeche Mode, Duran Duran, David Bowie, the Beatles, Led Zeppelin, Lynyrd Skynyrd, Vivaldi’s “Laudate Pueri” and “Stabat Mater,” Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue, Ladysmith Black Mambazo, music from Mali, Gipsy Kings, Terry Riley, Philip Glass, Kate Bush.

Chapter 11: 1930s and 1940s big band jazz, Wagner’s Tristan and Iseult, Parsifal, and the Ring.

Chapter 12: New classical music, Bach’s St. Matthew’s Passion, contemporary opera.

And honorable mention for chapter 1 must go to the unforgettable television series based on the wildly popular book by Iraj Pezeshkzad, My Uncle Napoleon (Da’i Jan Napoleon), that so deftly captured the dynamics of the social strata around the turn of the twentieth century, which an entire nation eagerly watched debut on Iranian television, one episode per week, just before the revolution.

But above all, silence, my favorite sound.

April 2019

Self-Portrait in Bloom (an excerpt)

by Niloufar Talebi

I first heard Ravel’s Bolero with Shamlou and my father, the three of us standing and staring at the gramophone as if it were a stage at a concert hall. I felt a connection between the crescendo in Bolero and the soaring buildup in a scene of one of the regime’s propaganda films pushing the agenda of Islam. The scene was a long shot of a caravan of the prophet Mohammad’s followers traversing a desert landscape against a dramatic sky. Perhaps it was the exodus from Mecca to Medina. The music evoked momentousness, a climax. Feeling the connection, I remarked, Amoo—meaning uncle, how male family friends are addressed in Iran—Shamlou, this is like that scene in the Mohammad film when they are crossing a desert. He laughed, missing the point I intended to make, admittedly not made well, and said, Except that those people were going—and then he showed a downward gesture with his arm—the opposite way. I was deeply embarrassed at not having posed the observation more specifically. What if he thought I had newfound religious zeal?! I might have spoken up to clarify that I was referring to similarity in musical buildup. But alas, I did not. I had not yet learned how to be laser sharp with language, to make space for myself when my first try did not resonate. So many dimensions budding in me at that time that I was not communicating. The world was opening itself to me in continuous waves.

I first heard Ravel’s Bolero with Shamlou and my father, the three of us standing and staring at the gramophone as if it were a stage at a concert hall. I felt a connection between the crescendo in Bolero and the soaring buildup in a scene of one of the regime’s propaganda films pushing the agenda of Islam. The scene was a long shot of a caravan of the prophet Mohammad’s followers traversing a desert landscape against a dramatic sky. Perhaps it was the exodus from Mecca to Medina. The music evoked momentousness, a climax. Feeling the connection, I remarked, Amoo—meaning uncle, how male family friends are addressed in Iran—Shamlou, this is like that scene in the Mohammad film when they are crossing a desert. He laughed, missing the point I intended to make, admittedly not made well, and said, Except that those people were going—and then he showed a downward gesture with his arm—the opposite way. I was deeply embarrassed at not having posed the observation more specifically. What if he thought I had newfound religious zeal?! I might have spoken up to clarify that I was referring to similarity in musical buildup. But alas, I did not. I had not yet learned how to be laser sharp with language, to make space for myself when my first try did not resonate. So many dimensions budding in me at that time that I was not communicating. The world was opening itself to me in continuous waves.

I was fortunate. I had sensitive, passionate parents who listened and heard and felt every wave and nuance and turn. I learned early to hear, watching my parents respond to the hush at the stillness and pause of the Beethoven second movement, the heroic journey of the piano toward the triumphant ending in the third, to soar and be filled with emotion, to listen with the large organ of the whole body. I learned that the concerto was the conversation between the solitary voice of the instrument and the orchestra, metaphor of the Great Conversation of life. It was all innocent, the beauty pouring into my wide eyes and my bone-knowing. And the hungry turning of the glossy pages of the orange book. We hear these pieces, these old friends, again and again, recited to us by interpreters who bring us back to indivisible essentials captured in those capsules of perfection.

If there were ever to be a soundtrack of those four years in Iran, it would be Rachmaninov’s second piano concerto. I listened to the recording we owned—another one now lost to me—so many times that it has been difficult to listen to any other version whose even slightly differing tempi are jarring to my ears, skewing the weight of those sweeping emotions, chords of catastrophic gloom. But it has been difficult to listen to any version at all. Even past my immediate rejection of tempi, the music transports me straight back to a world crumbling before my eyes, the weight of my adolescence without guidance in matters of puberty and boys, a home undergoing seismic shifts, a people on alert, murdered, humiliated in coerced public confessions, women disfigured by acid thrown in their faces for reasons ranging from improper hejab to the audacity of visibility in society.

Rachmaninov’s second piano concerto is for me all these emotions pent-up, of my being rewarded for being a Good Girl and doing housework when my mother was on periods of bed rest in her turmoil for having been born in the wrong time and place without a channel for the expression of these truths. Rachmaninov’s second piano concerto is my people’s anguish passed on to me. But mostly, it is my own loss of innocence. My own transformation from child to having-seen.

There was in my father’s demeanor, behind the silences, an unspoken kind of demand, an invisible pressure cooker of expectation of something undefinable, a fulfillment of some moral obligation I owed to the universe.

Copyright © 2019 by Niloufar Talebi

Reprinted by permission of the author