Wagering on Love in Zeruya Shalev’s Pain

The pain has returned—in Zeruya Shalev’s latest novel, Pain (Other Press, 2019)—“like labor pains, [its waves] come every minute or two and wrap themselves around her body, sawing through her pelvis cage bone after bone.” Ten years after Iris was almost killed in a suicide bombing, the pain, reactivated by her husband’s innocent reminder of the anniversary, comes back to haunt her. Unable to function, Iris, a middle-aged school principal who lives in Jerusalem, goes to a pain clinic, but the specialist doctor who examines her is none other than her first boyfriend, Eitan. He left her abruptly thirty years ago and caused her far more pain than the attack itself. She never recovered from it and married Mickey without real love, with whom she has two grown children. Iris throws herself into a passionate affair with Eitan that may shatter the life she has slowly rebuilt for herself after their breakup. Will her new feelings of youth, adventure, and joy translate into a drastic separation from her family? Will she in turn inflict pain on them for the sake of her past love? The narration takes a speedy turn as Iris feels it is time “to do what she wants,” but her daughter, Alma, has fallen into a guru’s destructive influence in Tel Aviv, and she needs all her attention and help. Torn between her past, present, and future, Iris listens to her motherly instinct and sets out to save her daughter first.

Pain takes on many faces in the course of the novel, translated into English by Sondra Silverston, whether the physical pain of the attack, the emotional suffering of the spurned teenager, or the wrenching loss of Iris’s father in the Yom Kippur War at a very young age. Even the day-to-day harsh words between the couple and the jealousy between their children are painful, especially Iris’s conflict between her fragile daughter Alma and herself. Burdened with the guilt that perhaps she never loved Alma enough, as she could not be Eitan’s daughter, Iris suffers to see her grow more and more distant from her.

Pain too is a person here. For fear of being found out by her husband, Iris gives Eitan the code name Pain on her cell phone. Each occurrence of pain intermingles with one or several of the others in an obsessive examination of past events and present relationships. But love dominates the book more than pain. “There are many faces to love,” Iris writes to her pupils’ parents in her weekly newsletters, and she repeats it to each of her children when they at last get to talk together like adults. Whether it is her teenage fusional love that she feels has returned or her unconditional motherly love, her long-standing affection for her husband of twenty-five years or even the forgiving of her enemies, love is more potent than pain and will heal her and her family in the end.

Love dominates the book more than pain.

Contrary to the brief relief Iris’s extensive use of painkillers gives her, nothing could help her wave off the pain of separation from Eitan when she was seventeen. She let herself die in bed and only survived after long weeks because of her nurse mother’s decision to stick an IV into her. And from then on, “a simple low-intensity life was enough for her.” Even as an orphan since the early age of four, after her adored father was killed during the Yom Kippur War, she did not feel as abandoned as she did after the breakup. She married Mickey, a large, hefty man radiating solidity, the complete opposite of the slim and forever adolescent-looking Eitan, “because she knew he would never leave her.”

When she is reunited with Eitan, the upheaval in her life is such that even what moral values she had preached before, in her school or at home, are now obsolete. For the sake of keeping her romantic encounters with him secret, she now lies to all the people around her: husband, children, cleaning woman, school colleagues, and employees. Her lies build up in her a burden of guilt on top of everything else that at times lead to absurd quid pro quos and comical situations. For example, she angrily rejects the term “infidelity” brought about ironically by the cleaning woman from a piece of news she had just heard on the radio: “The percentage of infidelity in Israel has almost doubled in a decade,” moments after she almost caught Eitan and Iris having sex in the living room. Such moments of comical coincidences abound in the course of the novel, breaking into Iris’s flowing stream-of-consciousness monologues, adding to the many twists and turns of the plot, and accelerating the action of the story in a way that none of Shalev’s books did before.

Shalev portrays in Iris a beautiful feminine character, at once a modern woman feeling self-assured in her job as a patient educator and an efficient manager of her school, specialized in helping difficult students, and at the same time fragile in her doubts about her parenting. Iris, who neglected herself after she emerged from the attack’s surgeries and hospitalizations, at present dyes her hair “jet-black” like her defiant daughter the day before, takes much better care of her physical appearance, and is ready to plunge into the past bliss of her young love for Eitan. “Her body fuses with his in the total giving of herself she remembers from then and has never felt since.” To the ugly word “infidelity,” she opposes “miracle.” On the contrary, she thinks “she has never felt more faithful to herself.” But as Eitan starts asking her to leave her family, questions arise. Could she and Eitan redeem the past and live forever the “second chance they have been given”? Looking at her son, Omer, at the exact same age as the Eitan of her youth, he reminds her of the “enormity of the price” she had to pay. How can she leave him just now, when he soon is to be drafted into the army? Her anxiety for him as a mother, and as the child she was when her father died as a soldier, makes her feel guilty and torn even more about her options.

Like all of Shalev’s principal characters, Iris is obsessed. She is obsessed by her lost adolescent love, by all the details in the course of the fatal morning that led her to be caught in the attack, which she re-creates again and again. She is obsessed by her guilt at not having given her husband a chance at love, at not having given enough attention to Alma, whom she hears has fallen into the trap of a guru, surely because of her. Guilt also pervades her life because of all the lies she has to invent to meet Eitan. And now torn by the impossible choice between her present with down-to-earth Mickey and a future with the exciting, forever-adolescent Eitan, she reviews all her options and finds that what she thought was an empty life is on the contrary quite full. Of all her identities—wife, mother, lover—Iris ultimately chooses motherhood. In the face of the danger to her daughter, “she is Alma’s mother.” Her desperate attempts at saving her daughter in sweltering Tel Aviv, with the welcome help of one of her former pupils, lend a detective-novel quality to the end of the story. “To help our children is to give birth to them over again,” whatever the pain: “What other gifts come with both pain and joy apart from giving birth to a child—even when you are screaming in agony, you don’t forget for a moment that you are giving life.” Saving her daughter helps her in the end resolve her dilemma.

Shalev’s novels are explorations of the intimate fluctuations of the mind of her characters.

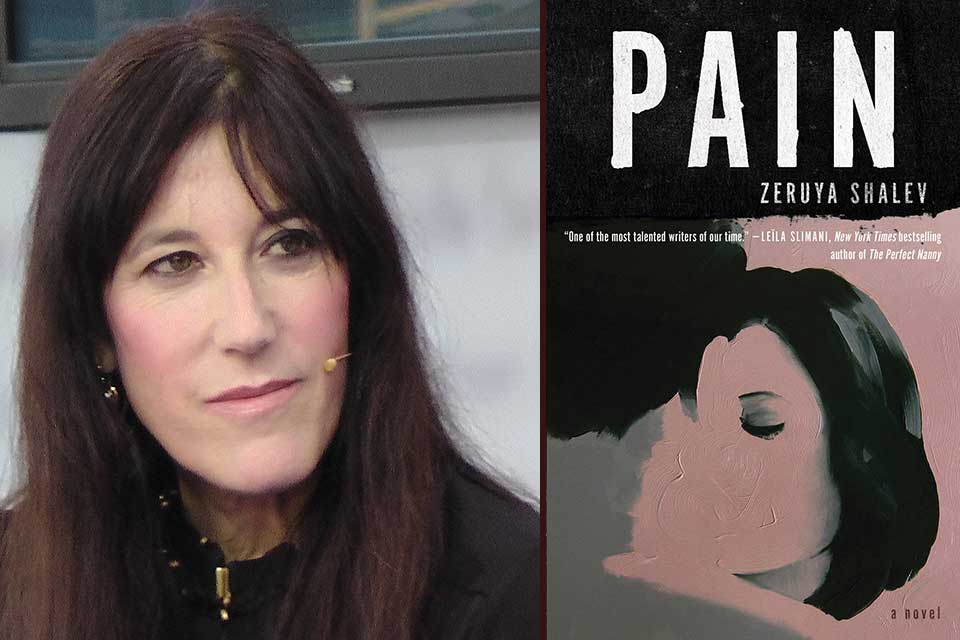

Shalev’s novels are explorations of the intimate fluctuations of the mind of her characters. She has created unforgettable figures in her four preceding novels, Love Life (2001), Husband and Wife (2004), Thera (2005), and The Remains of Love (2012). She is the most famous female Israeli writer abroad. Her novels, translated in dozens of languages, have received numerous international prizes. Her addicted readers see in her first three novels a trilogy, dealing primarily with declining love relationships within the couple, instances of infidelity, and (more and more) exacerbated motherhood. Her preceding novel, The Remains of Love, which won her more prestigious prizes, among them the French Prix Femina Étranger in 2014, focuses on the thoughts of a woman about to die. It. It is the impressive flow of consciousness of three characters instead of one—an ailing woman in her last days, her daughter, and her son. The daughter, whom she did not love from birth, obsesses about giving love and adopting a child, because her teenage daughter rejects her, and she herself is too old to conceive. The son, whom the old woman loved too much, fled from her and married too early, regretting it more and more acutely. His perpetual search for true love leads him to the most bizarre situations. It is a brilliant study of the complicated relations between parents and their children, and between brothers and sisters. In its conclusion, it was also seen as the most optimistic of Shalev’s novels.

Published in 2015 under the Hebrew title Ke’ev, and already translated in several languages, Pain is now available in English, thanks to Sondra Silverston’s precise and flowing translation. It could have been a far more difficult novel to read if the talented author had not interspersed numerous dialogues not devoid of humor in Iris’s intimate monologue. With the help of almost unbelievable twists and turns, the narration acquires a rhythm that maintains the reader’s interest throughout the story, almost frustrating them with its abrupt end. And still with her distinct style, her poetical metaphors pervade the novel. Tel Aviv at first welcomes the unprepared couple “with its glittering towers and their thousands of glowing eyes,” but when by day the distraught Iris is roaming its streets, desperate to reach her daughter, she “feels like a stranger in the infernal city.” Her impression is that “she has sunken into the sea, the air so damp and salty,” and furthermore “the humidity strikes her face like a used floor rag, exhaust fumes filling her heart.”

Shalev’s books are mesmerizing, and although mostly considered difficult or even stifling because of the closeness of the characters dealing with obsessive couple and family conflicts, readers cannot put them down before the last page. In a recent interview, Shalev said “family is the theater she prefers” and that what she “loves best is conflicts.” Pain is certainly about conflicts in the family, not just the resurgence of Iris’s past love threatening to destroy it. The ambivalent parenting relationships and the necessary rivalries between siblings still occupy a good portion of the plot. When Iris at last convinces her husband to drive to Tel Aviv and see for themselves what they only know as rumors, she reflects: “it seems as if until their last breath, parents will be arguing about who is to blame, who is a better parent, who is right and who is wrong.”

Rather than political, Shalev’s writing is intimate—she delves into the tiniest folds of her characters’ thoughts and emotions.

Rather than political, Shalev’s writing is intimate—she delves into the tiniest folds of her characters’ thoughts and emotions. The endings of a number of her stories tend to be “therapeutic,” as a few critics have already written. ln The Remains of Love, the once-monstrous mother manages before her death to make peace between her children, repairing all the harm she has done in a final gesture of love. It is this new quality of optimism that also appears in Pain, when all the family is reunited. Life in Israel appears mainly through the daily life of Shalev’s characters. In that sense, she seems to totally agree with the famous late literary critic Harold Bloom, who once said: “Literature is not an instrument of social change or an instrument of social reform. It is more a mode of human sensations and impressions, which do not reduce very well to societal rules or forms.” But as a few critics have reproached her for the noncommittal approach to Israeli society in her novels, maybe in Pain a few aspects of the novel come forward as more political than she would like them to be.

For example, when Iris cannot talk Mickey into visiting their daughter in Tel Aviv to check on the unpleasant rumors they heard, and equally cannot talk about Alma to busy Eitan in a hurry to return to the hospital, she opens her worried heart of a mother to a complete stranger, and no less than Moussa, the Arab restaurant owner in the village in the Jerusalem hills where she has just met Eitan. He listens to her quietly and gives her the advice she needs: talk to the girl’s father and go together to Tel Aviv. “Why is it so much easier to talk to a stranger?” she ponders. And about her sulking husband on the way to Tel Aviv: “Closeness creates so much pain and sensitivity, wounds and scars that every subject becomes too charged for a sensible conversation.” Why did she choose Moussa as a confidant? Is it because married to a Jew with three daughters, he is “living the most exciting fantasy in this region—coexistence?” Is this a hint at what Shalev thinks, that if people start listening to one another in Israel, there might be understanding between them at last? After all, Shalev herself was severely wounded in a terror attack in January 2004, and she writes about it for the first time in Pain. It could be that in this novel in particular, she has changed her view on politics in literature as “crude.” But it is not likely. She does not express any feelings of hate or revenge at the attack; all she seems to care about is the wellness of her family and of her pupils.

In her newsletters to the parents, Iris speaks about the redeeming power of forgiveness, citing Joseph forgiving his brothers, as one of the other faces of love. She announces to them her project for next year, called “The Other Is Me,” that will include “integrating the children of refugees into the school and [. . .] meeting children from the Arab sector, celebrate Jewish and Arab holidays, get to know each other directly.” This is as far as her politics will go: let’s talk and listen to each other. She is part of a growing movement in Israel, Women Wage Peace, not affiliated to any political party, that organizes regular meetings with women of all faiths and nationalities in the region in order to help change the minds of the people from fear and suffering to understanding one other. In the beautiful documentary movie Les Guerrières de la Paix (2018), she is briefly seen among the thousands of determined women who participated in the long march near the Dead Sea and in the Jordan Valley in October 2017. Typical of Shalev, she will not push herself to the forefront of a public cause she cherishes because of her celebrity.

Jerusalem