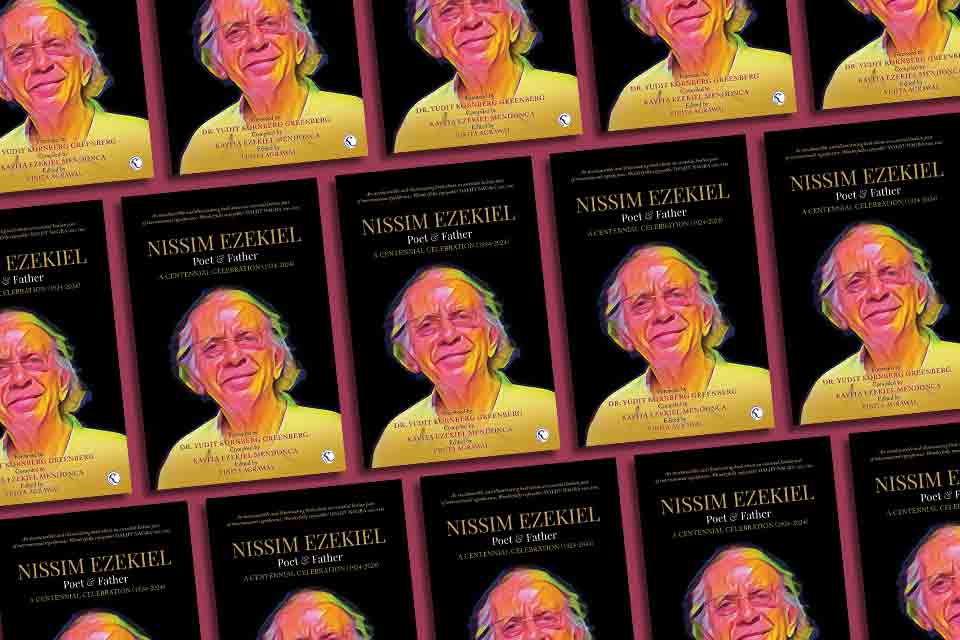

Remembering Nissim Ezekiel, Indian-Jewish Writer

A centennial celebration of poet Nissim Ezekiel compiled by his daughter, poet Kavita Ezekiel Mendonca, Nissim Ezekiel, Poet and Father (Pippa Rann Books, 2024) consists of a collection of memories, augmented by vignettes and historic records. Reminding the reader of Nissim’s appeal and complexity as a poet, editor Vinita Agrawal reflects: “A memoir requires perspective and insight in order to be beautifully portrayed.”

In part a rebuke to former collections that sought to sensationalize Ezekiel’s life by focusing on his personal life and any whiff of scandal rather than his poetic legacy in Indian literature, Kavita embraced the mammoth task on his one-hundredth anniversary by reaching out to those who knew him, in hope of garnering an authentic collective voice through interviews.

Many Indian academics believe Ezekiel was instrumental in raising the global profile and appreciation of Indian poetry in English. Becoming known for his writing in the language of the colonizer, Ezekiel has been quoted as saying he attempted to reclaim what was lost by colonialism by imbuing the bland English language with the vividity, color, and cadence that is recognized as Indianness; that linguistic distinction became valued as a separate form. In employing this strategy, he explored the complexities of displacement, identity, and the resilience of humanity through his writing as a Jewish Indian.

Others choose to give themselves

In some remote and backward place

My backward place is where I am.

(“Background Casually”)

There are rare insights into Ezekiel’s personal life; rare, given the family’s historic approach to privacy. As Kavita recalls, “If you come from a broken family, it is as if you spend a lifetime collecting broken bits of glass and trying to piece them together, in an attempt to form some kind of meaningful pattern.” By this she refers to her father’s choice to leave the family, causing social condemnation. These responses to her father, through poetry and prose, compile a tapestry of Ezekiel’s writing-life, alongside his daughter’s desire to become a poet in her own right and her understanding of the sacrifices made: “He simply wanted to do his life’s work without the shackles of domesticity. The things expected of him as a family man were impossible for him to do.”

“If you come from a broken family, it is as if you spend a lifetime collecting broken bits of glass and trying to piece them together, in an attempt to form some kind of meaningful pattern.”—Kavita Ezekiel Mendonca

As Raul Da Gama Rose writes in recollection: “I still read Nissim’s work, not simply to enjoy his poetry, but often to learn how to resolve a thought in danger of overtaking the heart of an emotion.” The recollections of his family and contemporaries lend a generational depth to this book that is stark and revealing:

I thought I heard him recite the poem

I wept, careful not to erase the lines

His voice mellifluous and poignant

He made me fall in love with poetry.

(“My Father Taught Me Love,” Kavita Ezekiel Mendonca)

Ezekiel’s contemporary, another Indian-Jewish writer, Shalva Weil, writes: “Today I realize one has to view Nissim in a wider perspective against the backdrop of the evolving Bombay cultural scene.”

Moving from focusing solely on Ezekiel, the book considers shifts in Indian society with regard to writing poetry in English and where future Indian/English writers have taken that initiative. Ezekiel’s contemporary and friend, Shanta Acharya, remembers: “Like Yeats, he treated poetry as the ‘record of the mind’s growth,’ which is how I came to poetry. It was and still is for me a subversive and solitary activity as much as a way of reaching out to the world.” The immediacy of these recollections relates the generational influence of writing in English:

Above all, my father loved us, his children

Celebrated us in verse and in rhyme

Named me prophetically

So I could write about him.

(“The Many Things My Father Loved,” Kevita Ezekial Mendonica)

Kavita’s recounting of her father became this centenary memoir; it is an evocative collection, transcending the boundaries of geographic location and offering a universal exploration of the bond between father and daughter as well as poet and poet.

Grasse, France