Sacrifices for the Truth: On Kenyan Writer Abdilatif Abdallah

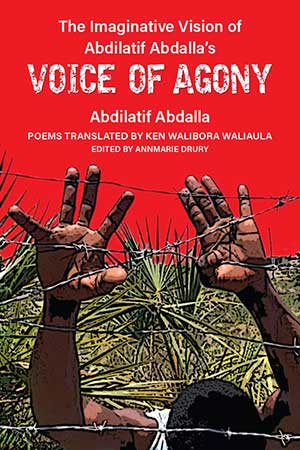

Abdilatif Abdallah (b. 1946, Mombasa) is a major Swahili poet who was, until recently, largely unknown to English readers. A beautiful volume of his work, The Imaginative Vision in Abdilatif Abdallah’s Voice of Agony (University of Michigan Press, 2024), has been edited and introduced by Annmarie Drury. Unfortunately, Ken Walibora Waliaula, the volume’s translator, was killed in an accident during the Covid-19 pandemic in Kenya.

Undoubtedly, Sauti ya Dhiki (Voice of Agony) is a major poetry collection in the annals of late twentieth-century African literature. Annmarie Drury, Ken Walibora Waliaula, and all the other contributors to this elaborate and ornately designed volume have done everything possible to situate Abdallah’s work in its proper context. They accomplish this by employing many perspectives—be they Swahili, African, or global—while encompassing myriad important cultural, artistic, and political referents.

Undoubtedly, Sauti ya Dhiki (Voice of Agony) is a major poetry collection in the annals of late twentieth-century African literature. Annmarie Drury, Ken Walibora Waliaula, and all the other contributors to this elaborate and ornately designed volume have done everything possible to situate Abdallah’s work in its proper context. They accomplish this by employing many perspectives—be they Swahili, African, or global—while encompassing myriad important cultural, artistic, and political referents.

In 1969, at the age of twenty-two, Abdallah was arrested by the Jomo Kenyatta regime. He was detained until 1972 for his anti-authoritarian stance, human rights advocacy, and in response to his political tract, “Kenya: Where Are We Heading?” (Kenya: Twendapi?). His uncustomary moral courage and acute sense of political consciousness cost him his freedom, but the loss also birthed a powerful poetic voice.

While held in solitary confinement in the Kamiti maximum-security prison, Abdallah began to compose a collection of poems, Sauti ya Dhiki, on toilet paper. These poems would later announce him as a major Swahili poet.

Mombasa, a key city of Swahili cultural and intellectual life, birthed Abdallah’s lucid, creative vision and uncompromising ideological stance. The city has been indelibly marked by a litany of broken treaties and disconcerting political betrayals. Mombasa is a confluence of Indian Ocean connections, socioeconomic and cultural interactions with the sultanate of Oman, ambivalent Portuguese incursions, and other colonial conquests and encounters. These historical realities have helped fuel Mombasa’s Mediterranean-inflected vibrancy, cosmopolitan aspirations, and coastal uniqueness.

Abdallah’s uncustomary moral courage and acute sense of political consciousness cost him his freedom, but the loss also birthed a powerful poetic voice.

Increasingly, the world is becoming more aware of Mombasa’s rich cultural and intellectual heritage through the work of scholars such as Kai Kresse and Alena Rettova. Kresse published Philosophizing in Mombasa in 2007, Swahili Muslim Publics and Postcolonial Experience in 2019, and his translation of a selection of Sheikh al-Amin’s Mazrui’s journalism was published a few years earlier. Rettova is noted for her work promoting William Mkufya, a Tanzanian novelist who also writes in Swahili. Annmarie Drury points out that “Abdallah’s poems resonate with distinctive subtlety and complexity” (xii). He is also a poet blessed with considerable existential range and experience. Such is the wealth of knowledge and culture to be discovered in the Swahili communities of East Africa.

Abdallah is a poet and a political activist of note. The following poem, “N’shishiyelo” (I won’t compromise), was composed by Abdallah during his incarceration.

I understand truth is unpalatable

For humans it’s poisonous, dangerous and beyond compare

Whoever speaks truth gains no popularity

Now I believe this; it’s true indeed true

Truth has imperiled me; for speaking it, my friend

Those to whom I spoke subject me to anguish

They view me as evil, more evil than Pharaoh

Now I know truth is not loved by many

The second stanza offers a slightly maudlin, wry assessment of the perils of truth seeking. The lines are measured, reflective, not infused with the uncontrollable rage or unguarded chutzpah one might expect from a young man of twenty-two. They also proffer a stark, well-informed illustration of the human condition, beyond the theatrics occasioned by flamboyant political grandstanding.

The direct and clear emotions expressed in “Jipu” (The Boil) are equally appealing;

I have a heavy heart; I’m not happy, as much I want to be

It’s all the same to me whether daytime or nighttime

My heart knows the suffering I’m undergoing

The worries and trepidation that torment me

I have a boil that has formed, giving me endless grief

Since it has afflicted me, I’ve had no solace

It’s my first time experiencing such an ailment

Its pain stabs like needle, I tell you

His torment isn’t merely physiological but impelled by intense political turmoil and anguish. Arguably, this politically induced torment attains its climax in “Kutendana” (Tit for Tat), in which Abdallah’s defiance seems to be in free flow, without the coarseness of mere sloganeering. Without missing a beat, he indicts those who truly need to be indicted:

Now what remains is your task, not mine

I’ll let you perform it so we can assist one another

If you accede to this, start flexing your brain

So you can undertake for me the task I’ll name

These three people who were found guilty

Judge each of them according to the law

Don’t fear anything or show favor to anyone

Treat no one unjustly, do not display pity

Ironically, Sauti ya Dhiki, Abdallah’s inimitable collection of poetry, won the Jomo Kenyatta Prize for Literature in 1973. A tyrannical regime was inexplicably compelled to honor one of its most avid and eloquent detractors.

During the 1960s, as most African nations were gaining political independence, a new scramble for the continent ensued under the implacable shadow of the Cold War between the Soviet Union and the West. Just as well that African literary arts and authors were drawn into this global, ideologically suspect network of intrigue, subversion, subjugation, and neocolonialism. Caroline Davis’s African Literature and the CIA: Networks of Authorship and Publishing chronicles the manner in which canonical African authors such as Wole Soyinka, Bessie Head, Lewis Nkosi, and Es’kia Mphahlele benefited immensely from the CIA’s largesse without necessarily being aware of it. The CIA had set up the Congress of Cultural Freedom at Paris in 1950, ostensibly as a way of broadening and consolidating American cultural power. Many of the African authors caught in this political manipulation went on to be household names in global literary circles. Abdallah was missed by the CIA’s dragnet, which may account for his relative obscurity with English audiences. Another reason for this late recognition of Abdallah’s considerable literary worth is a widespread unawareness—even on the African continent—of the incontrovertible depth and intricacies of Swahili high culture, even though Swahili remains one of the continent’s most widely spoken languages.

Furthermore, Swahili society doesn’t constitute a dominant political configuration in Kenya, so Swahili producers of culture are, arguably, minoritized as a result. However, Kenya’s foremost novelist, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o—whose career may have benefitted marginally from the cultural machinations engineered by the superpowers of the Cold War—wrote a succinct and insightful preface to Abdallah’s volume. Ngũgĩ points out that Abdallah “is independent Kenya’s first political and literary prisoner.”

Nonetheless, he’s quick to make an important distinction. During the colonial era, poets and musicians deemed to be part of the Land and Freedom Army—erroneously misnamed the Mau Mau—were routinely arrested and detained by the authorities. Horrifying stories about the torture, degradation, and dehumanization meted out to activists of the resistance movement have since come to light. Notable resisters of colonial servitude included Henry Muoria, Stanley Kagika, and Gakaara wa Wanjau. Eight years after Abdallah was detained, Ngũgĩ would himself be incarcerated at the same maximum-security prison by the notorious Kenyatta regime. And as Abdallah had done earlier, he would go on to write his novel, Devil on the Cross (Caitaani Mutharabaini)—initially in Gikuyu—on toilet paper.

This lavishly conceived and assembled volume includes a selection of critical essays on Abdallah’s work and life. Ann Biersteker also has an essay on Abdallah’s groundbreaking anthology, Sauti ya Dhiki, and the place it occupies in both Swahili and East African literatures. Meg Arenberg offers an article on rhymed, metrical translations of four of Abdallah’s poems, while Alamin Mazrui reflects on his encounters with the esteemed poet.

Kresse has translated the incendiary article Kenya: Twendapi? that got Abdallah incarcerated in the first place. In this transformative article, Abdallah castigates the Kenyatta regime for undermining democratic principles, entrenching authoritarian rule, and curtailing the civil liberties of Kenyans.

Abdallah remains an important voice for justice, human rights, and democracy.

After regaining his freedom and eventually relocating to Europe, Abdallah remains an important voice for justice, human rights, and democracy. He can rightly be considered “a global public intellectual,” as Ngũgĩ labels him. Indeed, Abdallah was awarded the 2018 Nichols-Fonlon Prize for Creative Writing and Contributions to the Struggle for Human Rights and Freedom of Expression.

What has Abdallah’s creative journey ultimately revealed? As a young man, he embarked on a singular quest that combined the romanticism and idealism of youth, unbowed political activism, and a potent artistic vision. Unlike most youthful adventures that are usually marred by recklessness, however, his quest ended up bequeathing an impressive literary legacy.

African Studies Centre, Leiden / ZMO, Berlin