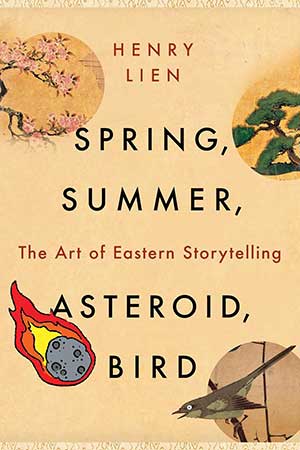

Understanding Eastern Storytelling in Henry Lien’s Spring, Summer, Asteroid, Bird

If you have ever taken a writing class in Europe or North America (aka the West), you have likely heard about the three-act structure. Story elements like the inciting incident, tension, central conflict, climax, and resolution have become almost unquestionable staples of good storytelling and can be found in every movie or novel. Henry Lien, the author of Spring, Summer, Asteroid, Bird: The Art of Eastern Storytelling (Norton, 2025), invites readers to apply a new lens to storytelling and introduces us to the four-act structure of Eastern stories.

Lien writes speculative fiction and teaches writing in the Writers’ Program at UCLA Extension. According to his website, he was born in Taiwan and now resides in California. This bicultural perspective is evident throughout the book in Lien’s understanding of how stories are structured and consumed across cultures.

Lien writes speculative fiction and teaches writing in the Writers’ Program at UCLA Extension. According to his website, he was born in Taiwan and now resides in California. This bicultural perspective is evident throughout the book in Lien’s understanding of how stories are structured and consumed across cultures.

Lien explains the Eastern four-act structure in terms of a short story titled "Spring, Summer, Asteroid, Bird," with each word in the title signifying one of the acts (Act One – Spring, Act Two – Summer, and so on). Throughout the book, he breaks down films, novels, games, and even poems from Eastern cultures or written by Eastern authors that follow this structure. Some of the well-known titles Lien analyzes include the movies Parasite, Everything Everywhere All at Once, and Rashomon, the novels Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World, Never Let Me Go, and the game The Legend of Zelda. Most of the analyzed works come from East Asian traditions, such as China, Taiwan, and Japan, with some rare examples from Indian and Middle Eastern literature. One of his central claims is that Western audiences and readers do love and understand the four-act structure despite commonly held beliefs to the contrary.

Lien breaks down films, novels, games, and even poems from Eastern cultures or written by Eastern authors that follow this four-part structure.

The book challenges Western media’s attempt to add diversity to their movies by casting exotic-looking actors or setting stories in superficially Eastern locations. His primary example is Disney’s live-action Mulan. He argues that adding Eastern aesthetics isn’t enough to tell Eastern stories and that creators must understand traditions, values, and themes that shape Eastern storytelling. This kind of cultural analysis is one of the recurring topics of the book. Before diving into the four-act structure, the author also breaks down the Western three-act structure and sometimes rewrites the four-act stories into three-act stories to demonstrate the difference. In the book’s third chapter (or act), Lin discusses collectivism versus individualism and shows how values shape what story structures prioritize (for example, asymmetry over symmetry).

One of the biggest takeaways from the book is the third-act twist marked by the arrival of the asteroid. This twist might manifest through the addition of a new element, a change in tone, or even the genre. Lien’s explanation of this twist, although simple, gives a fresh lens on stories like Parasite, where the second half of the story shifts into something unfamiliar yet compelling.

That being said, the book can sometimes homogenize Eastern traditions by grouping a variety of cultures—Chinese, Taiwanese, Japanese, Indian, and Middle Eastern—under the umbrella term “Eastern.” There’s also an occasional tendency to view Eastern and Western storytelling in a binary way, and the comparison can occasionally feel reductive of Western storytelling. However, the author seems aware that some parts of the book can be perceived as such and frequently addresses these issues.

The book demonstrates a good balance between theoretical discussion and case studies. This is not a traditional writing-craft manual, so don’t expect any writing prompts or do’s and don’ts of writing. However, writers can also find some ideas to experiment with. Neither is it a deep, academic exploration of Eastern literature, traditions, and history. The book is what it says it is: an introduction. Lien’s language and approach are accessible and engaging. It’s aimed at general audiences, mainly Western readers, who love reading across cultures and watching Miyazaki movies.

Norman, Oklahoma