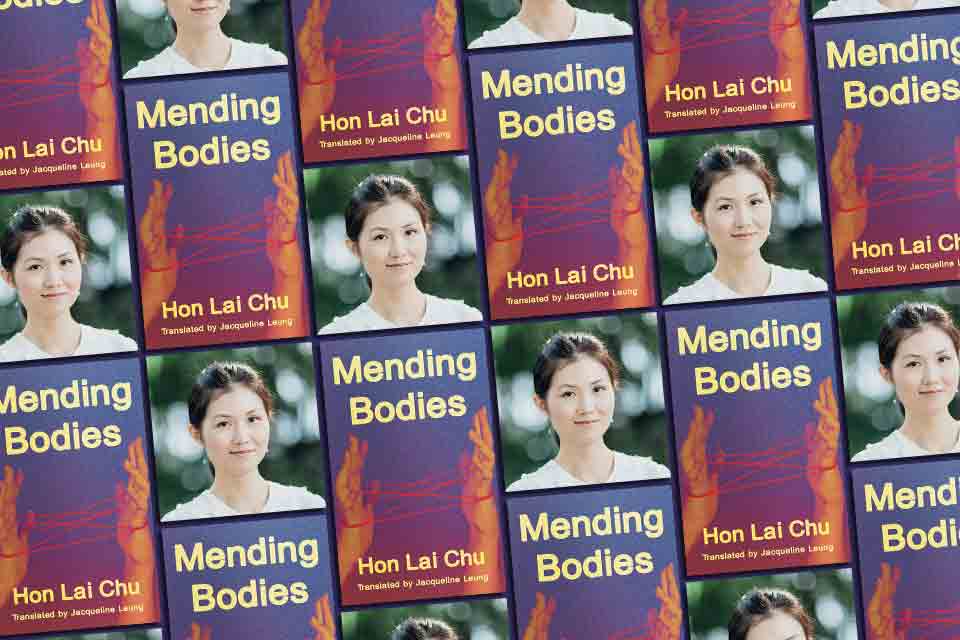

The Tyranny of Togetherness: Dystopia, Identity, and the Body in Hon Lai Chu’s Mending Bodies

In Hon Lai Chu’s newly translated novel Mending Bodies (Two Lines, 2025), intimacy becomes a matter of state policy. The Conjoinment Act, a fictional government mandate that requires or encourages couples to undergo surgical fusion, is not just a grotesque medical procedure—it is a literalized metaphor for the loss of autonomy under systemic control. First published in Chinese in 2010 and adapted for the stage in 2014, the novel has gained new urgency in its 2025 English translation by Jacqueline Leung. As Hong Kong continues to reckon with the aftermath of its political unmaking, Mending Bodies arrives like a ghost from the future, eerily prescient and painfully present.

Set in a vaguely defined city that mirrors Hong Kong, the novel presents a collage of reclaimed land, vanishing hills, and colonial architecture repurposed into medical facilities. The citizens speak in the sanitized language of healing and harmony. But beneath that language lies a deep and visible wound. The novel follows a university student researching the history and psychology of conjoinment, a journey that ultimately leads her to undergo the procedure herself. Her body becomes both subject and object—a site of research, resistance, and ruin.

In the spirit of Orwell and Atwood, but with a distinctly Hong Kong sensibility, the narrative explores how conformity can be achieved not through force but through carefully cultivated desire.

Hon’s dystopia is not built from steel and surveillance cameras but from social pressure and internalized ideology. In the spirit of Orwell and Atwood, but with a distinctly Hong Kong sensibility, the narrative explores how conformity can be achieved not through force but through carefully cultivated desire. People believe they want to be joined. They speak of togetherness as virtue, solitude as sickness. One psychologist on a talk show cheerily asserts, “No person is complete on their own.” It is such logic that authorizes the knife.

If this sounds eerily familiar to observers of Hong Kong’s political descent, it should. The novel’s Conjoinment Act echoes the region’s post-handover integration into mainland China—a process promoted as reunification but experienced by many as recolonization. The so-called return to China left many Hongkongers in a state of existential limbo, trapped between nationalist expectations and a local identity they were told to transcend. Hon gives this psychic dismemberment a physical form. To live under the Conjoinment Act is to live in pain. And yet, as one character cynically notes, it keeps people “too tired to protest.”

Through the embedded voice of the protagonist’s thesis, Mending Bodies analyzes itself. Her writing incorporates references to Michel Foucault’s theory of biopower—the idea that modern states exert control, not by killing, but by managing life itself. The act doesn’t annihilate its subjects; it makes them manageable. It rearranges their limbs, shortens their stride, slows their will. Erich Fromm’s psychoanalytic theory also haunts the text: the protagonist notes that many conjoined citizens suffer from what Fromm called the “masochistic character,” the tendency to surrender freedom in exchange for comfort, approval, or the illusion of safety. The tragedy, the novel suggests, is not that people prefer their shackles but that they are trapped by hope—hope that love or duty will transcend pain.

The tragedy, the novel suggests, is not that people prefer their shackles but that they are trapped by hope—hope that love or duty will transcend pain.

Take Aunt Myrtle, for instance—a once-hopeful woman who embraces conjoinment with romantic optimism. She chooses the surgery not because she is coerced but because she believes in a future of mutual support. Her reality, however, becomes a bureaucratic and anatomical nightmare: constant pain, stifled intimacy, blurry vision, and a husband who slips into silence. When she finally voices doubts and reaches for painkillers, the state doesn’t intervene, but her neighbors do: with concern, not violence. They confiscate her pills. They urge her to adjust her attitude. Her suffering becomes a matter of public wellness. The cruelty is communal, the policing done by peers who, like her, are only trying to survive the mandates of their time.

Then there are Evelyn and Josephine, fictional conjoined twins discussed in the protagonist's thesis. Evelyn is terrified of separation but agrees to it nonetheless, not because she believes it will set her free, but because she quietly hopes that both of them might die in the process. That, for her, is the closest thing to peace. Josephine, by contrast, longs to be unbound. She yearns for independence, not out of resentment but from an aching desire for solitude, for the possibility of an identity not shaped by constant proximity. Yet it is Josephine—the physically stronger of the two—who dies on the operating table. Evelyn wakes alone and immediately knows what has happened. She is not surprised they didn’t both survive, but the fact that she, and not Josephine, lived feels like a cosmic mistake. In losing her sister, Evelyn also loses the only framework of meaning she’s ever known. She is told she will never walk again. She continues on, haunted and hollowed. The metaphor is devastating. For some, the ordeal of disconnection—of reclaiming one’s individual body and self—can be more unbearable than the condition that preceded it. In this world, and perhaps in ours, the pain of separation can outlast the pain of attachment.

Hon Lai Chu writes with surgical precision. Her prose, rendered beautifully by Leung, moves between clinical detachment and visceral anguish. The metafictional structure—a story nested in a thesis nested in a story—echoes the recursive traps her characters inhabit. Even the protagonist’s body becomes a research site. When she describes the festering wound postsurgery, her professor responds: “Your research has just begun.”

Mending Bodies joins a growing canon of sinophone dystopias that use allegory to navigate the unspeakable.

Mending Bodies joins a growing canon of sinophone dystopias that use allegory to navigate the unspeakable. Alongside Dorothy Tse’s Owlish and Lau Yee-Wa’s Tongueless, it reflects a trend among Hong Kong writers to reimagine resistance not through slogans but through nightmares. These works don’t tell us what to do; they show us what might happen if we do nothing.

By the time the narrator begins to dream of reclaiming her body, it is unclear whether she still can. That ambiguity is the novel’s final cut. Mending Bodies doesn’t offer liberation. It offers a mirror: bloody, fractured, and uncomfortably close to the skin.

University of Toronto