Through the Long Darkness in Jonas Zdanys’s Three White Horses

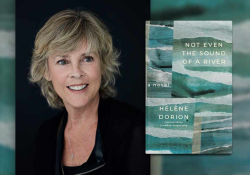

Jonas Zdanys is a master lyricist. The bilingual poet (English and Lithuanian) displays his versatile ability with a variety of poetic styles in several recent collections. In Red Stones (2016), in collaboration with Steven Schroeder’s painting, Zdanys features consistently metered, twelve-lined poetry. He skillfully accomplishes this form without violating language or context. His prose-poem collection, The Kingfisher’s Reign (2012), exhibits a rare cooperation with verse and scene. They are some of the finest prose poems of which I am aware. Thin Light of Winter (2009) presents a richly satisfying mediation, partly in tribute to his Lithuanian family in the former Soviet Union. St Brigid’s Well (2017) is one long lyrical poem in which he explores the lyric and place. It is an uncommon joy to find a poet so adept at a variety of poetic forms and linguistic styles, especially while maintaining such an intense, interesting, and beautifully haunted lyricism.

Jonas Zdanys is a master lyricist. The bilingual poet (English and Lithuanian) displays his versatile ability with a variety of poetic styles in several recent collections. In Red Stones (2016), in collaboration with Steven Schroeder’s painting, Zdanys features consistently metered, twelve-lined poetry. He skillfully accomplishes this form without violating language or context. His prose-poem collection, The Kingfisher’s Reign (2012), exhibits a rare cooperation with verse and scene. They are some of the finest prose poems of which I am aware. Thin Light of Winter (2009) presents a richly satisfying mediation, partly in tribute to his Lithuanian family in the former Soviet Union. St Brigid’s Well (2017) is one long lyrical poem in which he explores the lyric and place. It is an uncommon joy to find a poet so adept at a variety of poetic forms and linguistic styles, especially while maintaining such an intense, interesting, and beautifully haunted lyricism.

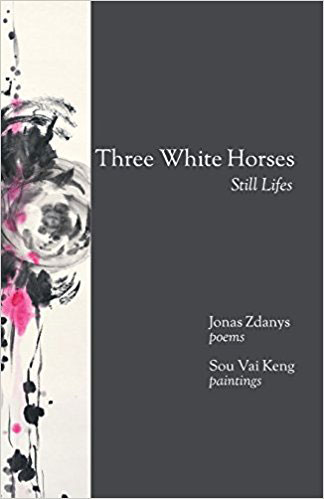

In Three White Horses: Still Lifes (Lamar University Press, 2017), Zdanys once again exudes a magnificent display of language, probing the psychology of winter. This collection moves darkly toward us in a free-form, dreamlike reflection, a liminal sensation occurring in the deep of night. In this “allegory of winter,” a lyricism flows from speaker to reader in a spellbinding entrapment. For example: “I push against the cold damp walls / of this place, outlined by no rules and / modulating this hard pursuit, and time seeps / away slowly to a desolate mark” (“The counterpoint to grace leads to a cave”). The awareness of winter intensifies the longing for light. With this, the book reflects the still-life form while simultaneously embodying an ethereal, soul-enthralling, mystical longing. We are moved almost languishingly through the enduring darkness of night, within a shadowed longing for light. A numbing existence, ironically, vivifies fleshly, corporeal, human desire.

Three White Horses reflects the still-life form while simultaneously embodying an ethereal, soul-enthralling, mystical longing. We are moved almost languishingly through the enduring darkness of night, within a shadowed longing for light.

Having read a number of his English works, some Lithuanian translations, and having heard him read from his work, I am persuaded that his ability of language—his precision, his power—is a paradox. He masters the use of language, not because he seeks dominion over it. This poet doesn’t control language or use it (as some amateurish, dramatic grab for attention); rather, he listens, feels, senses the living art that even common language makes possible. He allows language to form his very soul, illuminate his vision. I’m not exactly sure what Pound meant by the “luminous detail,” but I sense that Zdanys is as close to consistently revealing luminosity as anyone. His work glows without gaudiness. His acute sense of detail shimmers in his phrasing.

An enthralling bonus, in Three White Horses, the remarkable artistic talent of Chinese artist Sou Vai Keng accents his words. Her abstract ink paintings, like vivid clouds, softly hover close to a remembered summer dusk. They invoke a mysterious dark glow of a winter sunrise. The collaborative effect is real. The imagined, symbolized “allegory of winter” becomes pronounced in this collaboration.

Considering the conceptual bases that has made still-life painting a viable artistic endeavor no doubt helps us identify with the speaking voice in this book. An innovative approach to Memento Mori and Vanitas seems to shadow the speaker’s courageous attempts for clarification throughout the book:

These memories come and go

more often now and time takes me

in the darkness by surprise.

I do not want the silences of either.

I watch this winter night curl up

in smoke as God’s mystery covers

the far corners of the earth

like snow that falls for a hundred

years on every living thing.

I see your face in each falling seed,

breath with your breath in the frozen glass.

In the white stillness of this room,

in the final minutes of a sudden dream,

I bear the name that I’ve been given.

(“I remembered white butterflies”)

Zdanys captures the chaos of light, the mysterious affinity with darkness, and in profound cooperation with language, he interchanges these feelings of chaos, mystery, longing, and contentment—bringing the horses to life, even as winter ever-so-slowly dies. As winter grudgingly gives way to the distant hope of renewed light, we realize, perhaps tragically, perhaps futilely, that death is a process in which psychological or even spiritual awareness increases as the possibility of renewal in fact fades. Each renewal of life moves one closer to the greater, lasting dark—a separation from the body. Reflecting this, the human voice, with its uncertain restraints, becomes even more pronounced. The image of white horses invokes a variety of mythological possibilities, which, I believe, readers are free to associate from a variety of traditions within various cultural-historical contexts.

The Three Horses allegory provides a symbolic backdrop for human longing mixed with the inevitable: “The clock strikes midnight / . . . It had snowed all day, the sky fading / to brittle knots / . . . And the sky turned dark as a wilted rose, / black and brittle at the root. / And the shadows leaked unfocused / at the center and the edge” (“The clock strikes midnight”). It is too simplistic to say the speaker moves from dark night to the dawning light of morning. That movement is implicit, though the struggle occurring in the darkness—the wonderful, valiant, intimidating darkness—anticipates coming light. But the anticipation is wrought with struggle, and its outcome is uncertain. The poet’s writing is an act of faith in the best sense of the humanistic/Catholic (universal or even religious) tradition.

Too often, contemporary readers (especially Americans), schooled to eagerly anticipate the light, to celebrate the arrival of daylight, cheapen, diminish, or otherwise fail to appreciate the darkness. Three White Horses serves as an unhurried guide through the long darkness—not fighting but embracing its necessary tenure. This is yet another significant contribution to the literature that affirms humanity’s most vital quest, realized not by denial but by honest, artistic confrontation.

East Central University