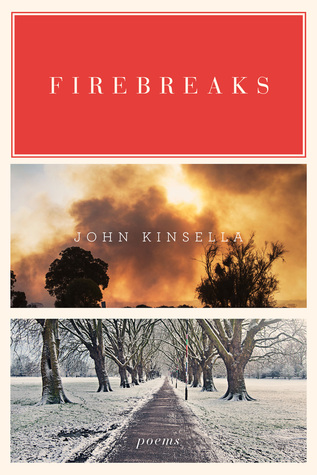

A Pause amid the Storm in John Kinsella’s Firebreaks

Poet John Kinsella inhabits and lends voice to the landscapes around him in Firebreaks.

In Firebreaks (Norton, 2016), the title John Kinsella chooses for his twenty-third collection of poetry, the poems stand against the burning of memory and/or events he experiences. Displacement, discomfort, puzzlement over injustice, mainly toward the environment, and the harsh environment itself are some of the topics.

Firebreaks—a ditch, road, creek-bed, or whatever acts as a barrier to the spreading of wildfire—appear throughout the book. “I walk them again – firebreaks / recuperating as ground – thinly – a splash of wild oats / seedlings, ‘comforting’ blanket of green almost everyone / waits for . . .” (“Coda: Walking the Firebreaks”).

Kinsella writes of his home and its surroundings in Western Australia in two parts, “Internal Exile” and “Inside Out.” His poetry circles a sense of place, respect for the land, environmental responsibility, travel, and living in harmony even with the undesirable critters. A whole group of poems is devoted to mice in the walls of his house.

Towards midnight, I set out across the block

with a mouse in the ‘humane trap’: to release

into a moonless dark, up near the western fence,

among granites and fallen trees, dry and whittled-

back by the sun, wind, and entropy: refugees

for the little gray tremblers transferred from the house

in this time of ‘mouse plague’.

(“Freeing a Mouse from the Humane Trap Around Midnight”)

Parrot, owl, bobtail, fox, kestrel, feral tomcat, falcon, eagle, echidna, shingleback lizard, snakes, ants, and bees inhabit the book.

In “Doe with Large Joey Snuggles Against the Hot House as Fire Approaches,” Kinsella writes: “Too many roos have suffered in this burning-up / of country, out of all patterning, without / volition. She doesn’t need to suffer in similes, / in analogies with inanimate objects, human devices.”

Kinsella’s new poems are a reminder of environmental awareness, preservation, and wonder at the natural world. In the end, they evolve into a universal concern for civilization and a desire to live in concert with natural patterns.

In this substantial collection, Kinsella’s poems are spokesmen for his life. His everyday details rise to significance in the natural formations of his words. His craft is evident. He is observer and recorder of storms, fires, ecology, politics, and principles of reciprocity.

Firebreaks are

so often jumped – wide, straight, curved, steep – and we

can’t create the colonial myth that will make them indelible.

They will grow over; we will cut deeper next time.

(“Coda: Walking the Firebreaks”)

Kinsella’s new poems come together in a poignant and relevant work. They are a reminder of environmental awareness, preservation, and wonder at the natural world. In the end, they evolve into a universal concern for civilization and a desire to live in concert with natural patterns.

Spirits of the land, God arching overhead but never above, I desire

No more than to be part of this house at Jam Tree Gully, the environs.

I have peace in the company of weebills and red-capped robins,

And when the rains come and wash through Bird Gully I am replete.

(“Hermit’s Song”)

Kinsella’s voice speaks from another land, yet is pertinent wherever it is heard. In a world that seems to run on economic gain and exploitation of resources, Kinsella’s work itself is a firebreak. The world probably will continue to burn, so to speak. Its methods of operation have been in place a long time and will continue to run with the momentum. But Kinsella’s voice is a reminder somewhat of God’s “Where were you?” speech from the Book of Job: “You can come so far and no farther” (38:11). God is speaking to the waves of the sea in that passage. In the passages of Kinsella’s work, it is a voice against progress in the way the world sees it.