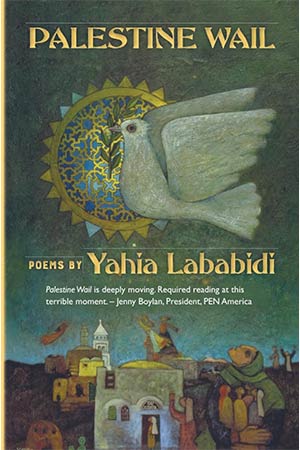

Palestine Wail by Yahia Lababidi

Wakefield, Québec. Daraja Press. 2024. 116 pages.

“To write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric,” wrote Adorno in 1949. Yahia Lababidi’s new volume—the poet’s eleventh—Palestine Wail, affirms how “during a genocide, most words lose their meaning,” they become uneasy, while tears and kindness speak more accurately. On a certain level, then, violence affects language fundamentally, as Adorno intuited. The genocide of the Palestinian people, carried out by the Israeli army since 2023, has indeed put language to shame.

Those who speak up on behalf of Palestine are forced into a regime that has been analyzed under the rubric of the “perfect victim”: even as the Palestinians are being massacred, they must not be allowed to say a disagreeable thing—and my earlier statement about genocide would have referred instead to a “conflict, that started with the unprovoked attack by Hamas of 7 October.” The silence and complicity of Western nations regarding the extermination of the Palestinian people is an important theme for Palestine Wail, in such poems as “During a Genocide,” “Say Something” (“If you’re uncomfortable saying Genocide, / say mass murder, / say boneyard [. . .] At least, say not in my name”), and many more. Lababidi voices the loneliness and despair that accompanies massacre: why is Palestine surrendered unquestioningly to its killer? He also asks whether the rest of the world should expect to see humanity and reason restored when the genocide is “over”: “Did you notice / the eclipse / is here to stay?”

Loneliness adorns Lababidi’s language; his words are clothed in it. This being enveloped in loneliness and abandonment opens the second, mystical movement of the volume, one that would respond to a philosophical and theological intuition from the same period as Adorno’s but, somehow, is diametrically opposed to it: “it does not seek a supernatural cure for suffering, but a supernatural use of it”; the remarkable position that Simone Weil indicated of Christianity in Gravity and Grace—there will be mystical thinkers within Islamic tradition that I am unaware of, and Rumi is invoked in the introduction. If Palestine is abandoned to its death, poetry bears witness. The work done here does not explain or make sense of suffering but, in recounting suffering, realigns it with dignity and transcendence.

Palestine Wail is at every moment a protest and a prayer, as evinced by the extraordinary, devastating poem “Summary”:

The hands were made to clasp

the knees designed to bend

the body created to pray.

What else is there to say?

The mouth was shaped to gasp

the eyes drawn to attend

the soul commanded to obey.

What else is there to say?

The memory was wired to lapse

the heart fashioned to rend

the will inclined to betray.

What else is there to say?

Both protest and prayer, Palestine Wail is a work of hope.

Arthur Willemse

Universities of Maastricht and Hasselt