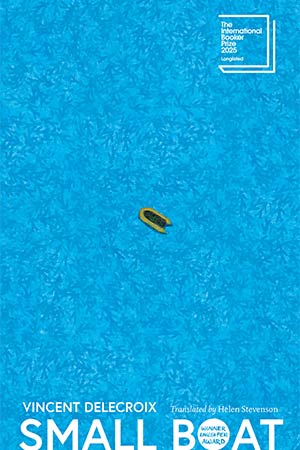

Small Boat by Vincent Delecroix

Leeds, UK. HopeRoad. 2025. 122 pages.

In Small Boat, Vincent Delecroix uses a first-person narrator as a vehicle to examine the issue of migration. Based on the 2021 tragedy in the English Channel when twenty-seven migrants died after their inflatable dinghy collapsed, this novella attempts to answer the question: Who is responsible for the deaths of migrants? In 2023 French authorities arrested five French soldiers for ignoring the pleas of the people in crisis. Readers are to assume the narrator—a woman recently separated and now raising a daughter on her own—is one of the fifteen people questioned in an inquiry attempting to assign blame for the disaster. The book recounts the interrogation of this unnamed woman by a woman agent assigned to understand and assign blame for the deaths. There are no easy answers to what seems like an open-and-shut case based on the evidence, which shows the woman ignored several distress calls, lied to the migrants by saying help was on the way, and redirected a ship that could have aided the men, women, and children who perished.

Shortlisted for the 2025 International Booker Prize, Small Boat illustrates how individuals are ensnared in the structural racism and hypernationalism that create the climate for such humanitarian disasters to occur. The narrator is callous, upset that no one focuses on the hundreds of people whose salvation she facilitated, and is a mother who realizes the sexism at play in her taking the fictional blame instead of the men “because I’m a woman as well, I’m meant to display a higher degree of sensitivity, humanity.” She doesn’t shirk responsibility, but she also refuses to be the scapegoat when wars and famine cause people to flee their homes in the first place and when countries do not want to take responsibility for those who wash up on their shores—those who even make it there alive.

Though the book does not let her off the hook, it certainly makes sure the reader interrogates all the systems at work that have created this wretched situation in which so many millions suffer. When asked to explain her lies to the dying man, she explains that in that moment she lost her humanity, yet “I am not a monster”; even as her voice denies any chance at life for those about to die, we are meant to believe that “it’s the voice of all of us.” Small Boat complicates what seems to be so simple: she didn’t help, so she is to blame. But what about the fact that no one saves the unhoused they pass every day? Or the woman who is drowning in poverty because her husband has left? The book does not make excuses for her; instead, it expands the circle of blame to implicate the reader and everyone in the world who contributes to the migration crisis.

Sections 1 and 3 are in the naval officer’s voice. Perhaps section 2 is the most evocative, told from the perspective of the man on the other end of the line, the man the distressed on the sinking dinghy are looking to for answers and hope. Those fifteen pages are only a small part of the book’s whole. They are anguishing to read as they detail what it must have been like for that man to call over and over for help, to watch as children float away from their mothers, as he slowly succumbs to the cold of the ocean. The reader cannot escape the horrors of those lost at sea and is therefore forced into the fold of those who deserve to carry some of the blame for those deaths. No one disembarks Small Boat without some culpability.

Colleen Lutz Clemens

Kutztown University