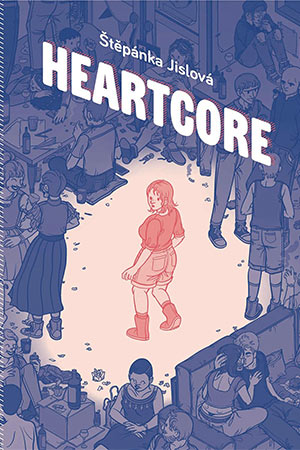

Heartcore by Štěpánka Jislová

Trans. Martha Kuhlman. University Park, Pennsylvania. Graphic Mundi. 2025. 231 pages.

Ever since the publication of the first volume of Art Spiegelman’s Maus in 1986, the graphic memoir has become a fixture in the world of graphic narratives. Writers and artists like Marjane Satrapi, Alison Bechdel, Roz Chast and Guy Delisle, among many others, have been read, taught, reviewed, and discussed at length. Now, Štěpánka Jislová’s graphic memoir, Heartcore, joins the list of very good narratives, but its flaws may keep it out of the pantheon.

Jislová’s drawings are vivid and distinctive, rendered in shades of grays and blacks with large swaths of red, and she effectively breaks out of traditional panel structure to create moments of emphasis and unusual character interaction or interior thought. There is astringent humor in her stereotyping of classic gender roles; interestingly, she doesn’t just show the female point of view and the struggle with beauty and objectification. Later in the book, through her friend Mike’s point of view, she tackles the trauma of being raised male to fit into a rather rigid society. She illustrates and describes these challenges well, including the need to show strength at all times and the burdens of being a short man.

When we first meet Stephanie, she is looking for love and suffering from all the emotional lability, turmoil, and insecurities of teenage girlhood. He loves me, I love him, this is amazing and oh no, he laughs too loud and he’s so annoying. It’s a story we’ve seen before, but as the volume goes on, we do root for the young Stephanie, who is trying hard to understand herself. She does this by going back through her Czech/Eastern bloc postcommunist 1990s childhood, her family, and her angst about her attractiveness until finally she meets Mike and decides she’s an artist. From this point on, the struggles get more interesting and the revelations darker and more traumatic.

The section titled Part Zero, which comes between Part Four and Part Five, is clearly a flashback and set up as the revelation of the past trauma and perhaps the root of her issues with life, men, and herself. Part Zero is rendered only in shades of red underscoring the examination of sexual trauma. In addition, the section offers a critique of Czech government and society for its attitudes toward abuse. But although the reader definitely feels for Stephanie, that emotional connection is intruded upon by a ten-page disquisition in Part Six of the narrative to teach the reader about differing kinds of attachment theory and various analyses of how different people define love. Clearly Stephanie is trying to cure herself in order to move toward a healthy relationship, but this portion of the narrative reads like a self-help volume or a psychology textbook.

The instructive nature of the book is clearly deliberate, since the endnotes include books and additional resources about both abuse and building loving relationships, but for this reader the didactic interruptions dampened the effect of an otherwise very affecting graphic memoir.

Rita D. Jacobs

New York City