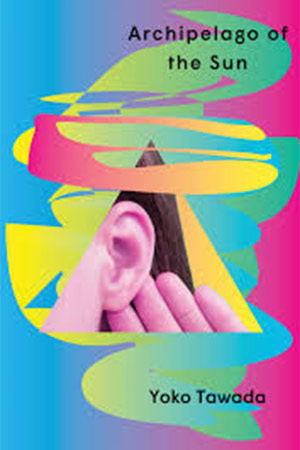

Archipelago of the Sun by Yoko Tawada

New York. New Directions. 2025. 224 pages.

Yoko Tawada’s fiction is packed with bracing ideas about language and community, but she has the lightest of touches, even when she’s grappling with nothing less than the fate of the planet. Though this novel takes place on a ship whose destination isn’t clear, it’s rooted in a steadfastly humane worldview.

Archipelago of the Sun concludes a trilogy, but readers needn’t have read its picaresque predecessors, Scattered All Over the Earth (2022) and Suggested in the Stars (2024), to find this one beguiling. The main character, again, is Hiruko. Like the author, she’s a Japanese woman who has lived part of her life in Europe. Hiruko is traveling by sea to find out what became of her home country, which seems to have disappeared. She’s accompanied by five friends from five different countries. Their encounters—with one another and some spectral fellow passengers—are invigorating and playful.

Setting the novel on the sea, where her articulate characters are in close proximity for a long period, enables Tawada to situate topical themes inside a Beckettian conceit. Acknowledging that we’ve poisoned our oceans, Hiruko muses about the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. Could the Japanese, whose homes sunk into the ocean, have built new lives atop tons of floating trash? Alas, her group’s itinerary may prevent her from finding out. For reasons none of them can explain, they’ve boarded a mail boat in the Baltic Sea, essentially treading water between the global East and West. As one of the travelers wonders, “Was this really the route we had chosen, of our own free will?”

Deepening their sense of befuddlement, Hiruko and friends soon realize that they’re sharing the ship with the ghosts of Witold Gombrowicz and Hella Wuolijoki. Writers shaped by humanity’s deadliest wars, Gombrowicz and Wuolijoki challenged their readers’ assumptions about national borders and language—two subjects that fascinate Tawada. Indeed, this novel is bemused by human-made boundaries between land masses—and besotted with all things lingual.

Tawada’s characters revel in wordplay and language-based thought experiments. They quarrel about adjectives, swap proverbs, and compare island chains to “a string of commas.” One suggests that if all languages were to forsake first-person speech, “egoists might disappear.” Another says he chose to travel with Hiruko “because she interests me linguistically.” He’s right to be interested—Hiruko is a rhetorical renegade. Frustrated by language barriers, she’s invented a “homemade” tongue she calls “Panska,” which has minimal punctuation and no articles or capitalizations. Here’s Hiruko summarizing a nap: “dozed off. in dream island i saw. island where i lived i forget not.”

Translator Margaret Mitsutani acquits herself well with this material and more traditional sentences, crafting understated, tonally apt prose. (Tawada is astute on the subject of translated literature. After one of her characters denigrates a translation he’s read, he allows that it’s futile to do so “when I can’t read the original.”) Tawada, of course, isn’t suggesting that Hiruko’s approach to conversation is pragmatic. Rather, it’s a fanciful gesture toward a world where, as her characters hope, deadly conflict could be avoided by sober discussion.

Hiruko’s adoption of a bespoke form of communication dovetails with Tawada’s interest in the fleeting nature of national borders. Countries vanish and maps become obsolete, but jingoism seems evergreen, her living characters and eloquent ghosts agree. This novel is a bighearted endorsement of reaching out to people who don’t share your preconceptions. To live “a life surrounded by foreigners,” one character says, is to resist provincialism and bigotry. If that doesn’t work, maybe hop on a boat. As Hiruko puts it, “there are no borders at sea.”

Kevin Canfield

New York