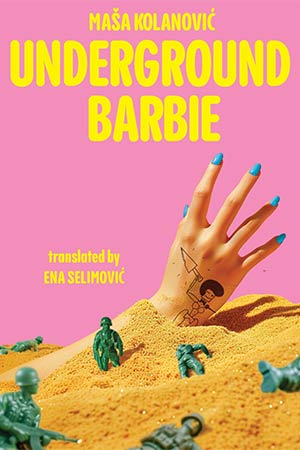

Underground Barbie by Maša Kolanović

South Portland, Maine. Sandorf Passage. 2025. 183 pages.

Having won both the European Union Prize for Literature and Croatia’s Vladimir Nazor Award–Literature in 2020 for a short-story collection, Maša Kolanović has received wide praise for Underground Barbie, a satire that critiques Croatia while examining the impact of the Bosnian war on a group of young Croatian girls. Here, Barbie and American media symbolize how Western popular culture and commodity capitalism have colonized Croatian minds. Thus, “real Barbies” far outrank inferior Balkan imitations, representing, per our nine-year-old first-person narrator, “a small but important token of prestige and prosperity.”

In the first of its fourteen chapters, the precocious “I” hilariously skewers Croatia’s secession from Yugoslavia and its recognition by the West as an independent nation. Suddenly, “Mister” and “Miss” replace “Comrade,” the League of Socialist Youth supplants the Yugoslav Union of Pioneers, Croatia’s coat of arms and a crucifix hang where Tito’s portrait once reigned, the Croatian red checkerboard decorates Converse high-tops, and most of I’s “friends with newly-out-of-fashion names—Sasa, Bojan, and Boro—moved away overnight.”

Barbie juxtaposes Outside—news alerts, edgy parents, sirens, incoming planes—and Inside—“I” and her Barbie-obsessed friends, who inhabit a high-rise apartment building outside Zagreb (Sloboština, literally “free city,” its name ironic since Tudjman controls it, its root shared by Croatia’s archenemy, Slobodan Milošević). As sirens announce the first air raid, parents drag terrified doll owners clutching carefully packed Barbies into the basement. “I” then suggests that should her building be bombed, reduced to ashes, “spewing flames and black smoke, life would still be worth living if my Barbie remained whole.”

Outside and Inside literally converge in chapter 2, when news crawls reporting Serbian planes aimed throughout Croatia “appear beneath the subtitles,” while the family watches the Twin Peaks finale to learn who killed Laura Palmer—“almost a matter of life and death.” But, “I” explains, “Our Croatian couch hit up against the deck of this dark world,” as Lynch’s detective simultaneously investigates Laura’s murder and “the firepower of the Yugoslav People’s Army and Serb extremists, having no clue about this part of the script.” Sadly, “I” and her family head to the basement to ride out the latest likely air raid without learning the answer.

Amid the ongoing war, the girls begin to see the basement as sanctuary, granting release from school, chores, and unwanted lessons while harboring their safe play. Yet the increased violence, sexual predations, and spatting parents of Outside penetrate Inside, and as the kids mature, they create ever darker games. Now they require a real Ken for their Barbies, but a three-year-old niece has decapitated the only one. Headless, dubbed Dr. Kajfeš, this doll—scripted to be oversexed and violent—dominates the girls’ imaginations. The chapter begins, “You should screw Bald Baby, then grab her wig in the middle of sex and put it on your head.” A visit from the dreaded niece looming, “I” equates the terror of her imminent arrival with that provoked by images of devastated houses, their still-standing walls graffitied with “This is moine!” or “Croat-seized.” Yet “I” finds the war in Zagreb not so bad —“we gained our very own space.” Their Inside games thus parallel the war games Croatia plays for land Outside.

The games intensify. Thus, for example, the planning of Ken and Barbie’s wedding and its actual aftermath occupy multiple chapters. But “I” cannot attend. For the first time literally Outside, accompanying her mother to her dreaded music lessons, she hears the air-raid siren: “I was actually quite scared . . . but on the inside of my outwardly unhappy self, I was still . . . relieved that music lessons were definitely out of the picture for today.” And she wonders if Ken will turn the wedding into a “bloodfest.”

As Croatia seems to be winning, the Barbie girls’ games increasingly take place Outside until suddenly, in chapter 14—“Farewell, Barbie!”—the war has ended. “I” asks, “War. How did the war even end? I don’t remember exactly.” The girls, now fourteen, focus on dates, dances, and “wearing Benetton jeans with a tight shirt so everyone could see the contours of our little breasts.” Gradually but inevitably, they discard the dolls and games that sustained them through the war.

Though skewering Western culture in sharply funny ways, Underground Barbie does not equal the sum of its parts. Childish stick-figure drawings permeate the text, awkwardly disrupting the narrative. We must either decode their relation to the context or ignore them. Next, though the girls evolve, they are flat characters, witnessed from a distance. No well-rounded character exists to claim our allegiance, and nothing really seems to threaten them. Thus, we have no emotional connection. Finally, as the convoluted games begin to occupy more and more textual space, navigating through them becomes tedious. Less would have been more. (Editorial note: You can read translator Ena Selimović’s conversation with Maša Kolanović about Underground Barbie on worldlit.org.)

Michele Levy

North Carolina A&T State University