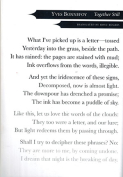

The Emissary by Yoko Tawada

New York. New Directions. 2018. 128 pages.

New York. New Directions. 2018. 128 pages.

In her latest book, Yoko Tawada describes a dystopian Japan after an unspecified disaster: the ground is contaminated, food growth is limited to certain regions, and animals are so scarce that many children have never seen so much as a rabbit. To protect itself, Japan adopts an isolationist policy so extreme that language is often self-policed to exclude words with foreign origins. This is the ambiguous future in which The Emissary finds its subject, Yoshiro, and his great-grandson, Mumei. But even more has changed than that—the youth are fragile, sickly, and delicate, while the elderly overpopulate, pulling their offspring and their progeny through as they become older and older themselves. Yoshiro worries and dotes on his charge, often racked with guilt, which he associates as an emotion of his generation. Mumei, on the other hand, is an optimistic and charming force of hope.

The style in which Tawada explores this juxtaposition is not unlike her previous novels, most notably Memoirs of a Polar Bear. Her narrators weave between past and present, their internal musings and the external setting they inhabit. She is generous with metaphors, sprinkling them through the perspectives of her narrators’ own fantastical imaginations, paranoia, or creative struggle. In one striking passage, Mumei vividly describes functioning as an octopus, and it is oddly relatable despite its absurdity.

Tawada expertly catches the feeling of trances—the normalization of adhering to laws that have no precedent for enforcement, or the daze of simple everyday routines. Her world-building is based on detailed descriptions that border on newspaper-variety mundanity, and in contrast her characters are described with vibrant vignettes of feelings and flashbacks while remaining vague as to their inspirations. The overall result is a dream world, not nightmarish but somewhat frightening and yet still familiar and comforting: health advice is still constantly contradictory; younger people are still the subject of their seniors’ complaints. The blend feels like a mess of the subconscious and conscious, each having important things to say to complement and strengthen the other. A master of convincing contradiction and amusing wit, Yoko Tawada has produced a novel with bits of humor quietly dominating like weeds in a barren posturban world.

Jacky Tideman

Oklahoma City