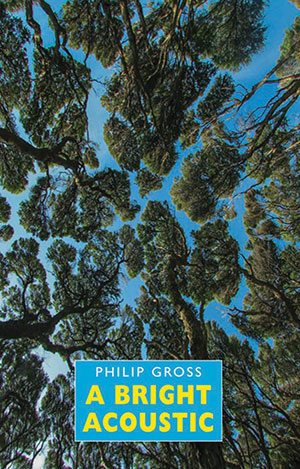

A Bright Acoustic by Philip Gross

Hexham, United Kingdom. Bloodaxe Books / Dufour Editions. 2017. 94 pages.

Hexham, United Kingdom. Bloodaxe Books / Dufour Editions. 2017. 94 pages.

The latest collection of poems from prizewinning British author Philip Gross, A Bright Acoustic, is a singularly attentive book. Blurring the boundary between sound and image until the two become entwined in an advanced synesthesia, wherein senses express through and even blend into each other, Gross employs layers of sense-metaphor to ply at the underlying physicality of the silent and the unseen, unearthed through an intensive process of listening and looking.

Multipoem sequences predominate in this collection, intricate investigations of different vantages of listening. Among these, “Time in the Dingle” stands out for the way in which it curates stillness and sound among the small happenings of the wood, drawing the reader into its immense attentiveness. To this end the speaker himself is concealed, rarely glimpsed save through the eyes of the forest creatures. Instead, we piece together the distant “clatter of toolkits” beyond the bounds of the dingle and wonder at a flash of “what? / hedge sparrows?”, finding in each moment of quiet a connecting sound-image, something to “stitch the world together, space / to matter.” The sequence’s most narratively moving moment comes in “Gone,” when Gross lays out a breathtakingly painful antithesis to this “Calculus of sound”: a picture of the dingle destroyed, “A great / unlistening.”

Though consistently hip-deep in metaphor, “Time in the Dingle” is never for a moment abstract, a virtue also shared by the briefer but equally enveloping sequence “The Breath of Things.” Brimming with a vital materialism that runs alike through city, mist, and seaside, these poems attend to the invisible animation that would permeate our world “if we could thin ourselves to subtlety / enough to hear it.” The reader attuned to the fine physicality of these poems may be frustrated by the abstruse parentheticals that disrupt “The Same River: thirteen variations on Heraclitus”—a feature that occasionally also afflicts the book’s last long sequence, “Specific Instances of Silence.” Nonetheless, the marvelously explorative and often spiritual poems in this culmination of listening bring an uplifting personal element that Gross seals in the final poem, “Written on Light.”

With verse and form as natural, cool, and playful as the settings in which many of his poems unfold, Gross maps a world of fine sense that exhorts us to a “tension . . . / of stillness” from which we can feel “The shiver / of sensations like the twitch / of metal cooling, on the surface // of the mind.”

Grant Schatzman

Norman, Oklahoma