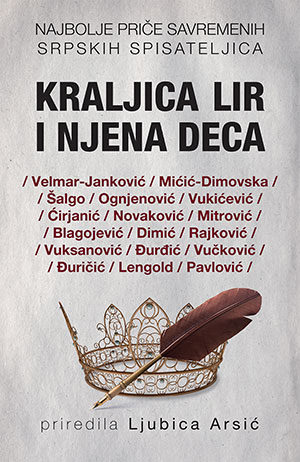

Kraljica Lir i njena deca: najbolje priče savremenih srpskih spisateljica

Belgrade. Laguna. 2017. 239 pages.

Belgrade. Laguna. 2017. 239 pages.

Renowned, awarded, and translated Serbian writer Ljubica Arsić (b. 1955) often promotes domestic and foreign women authors from past and present times. This time she has assembled a book of short stories Kraljica Lir i njena deca: najbolje priče savremenih srpskih spisateljica (Queen Lear and her children: The best stories by contemporary Serbian women writers) that is a wonderful example of the creative power of women in the Serbian writing tradition. Despite the fact that most of the authors included have received reputable domestic and sometimes European literary awards, women writers in Serbia have not been widely visible. Their writings have received very little critical attention. Selected editions of their works are rarely published, and, as authors, they almost do not exist in schoolbooks, nor are they valued in public debates as opinion-making intellectuals. As in the previous publisher’s anthologies of short stories based on a central theme, the introductory story is a stage-setting tale. A brilliantly chosen story, “Queen Lear,” by one of contemporary Russia’s most distinctive writers, Ludmila Petrushevskaya, underlines the intensity of women’s transformative roles and the specificity of their contemplation.

The anthology presents selections from seventeen authors of different generations and writing styles. In the generational scope of the book (1930–80), from Svetlana Velmar-Janković to Ana Vučković, writers born in the mid-twentieth century dominate. In the time of the great humanities debate over the relationship between ethics and critical thinking, it is very important to read again once popular, later politically persecuted, and today almost forgotten authors like Elvira Rajković.

A good number of the stories describe recent turbulent political times and consequences of the Yugoslav wars (Šalgo, Rajković, Dimovska, Đuričić, Novaković). While some writers were inspired by the history of Ottoman times (Velmar-Janković, Mitrović), others used Kafka’s metamorphosis and science fiction (Blagojević and Lengold) or offered a deconstruction of Cinderella (Vučković). Serbian women writers depict political and social relationships, often revealing different types of violence, illusions, and lies. As underlined in Pavlović’s story, women look for small things, but it always turns out they are big and unachievable.

The reader would benefit from more bibliographic details of the publishing years and translated works in each author’s short biography. Nevertheless, after reading these excellently written, interesting, and sometimes shocking stories, one might conclude that Serbian women writers are sharp-minded, discerning, witty, and powerful. For good reason, these authors see themselves as Kafka’s sisters.

Svetlana Tomić

Alfa BK University