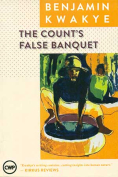

The Count’s False Banquet by Benjamin Kwakye

Milwaukee. Cissus World Press. 2017. 563 pages.

Milwaukee. Cissus World Press. 2017. 563 pages.

Accra-born novelist and Harvard-trained lawyer Benjamin Kwakye’s recent novel, The Count’s False Banquet, is a phenomenal tale with an enchanting spell. The book completes his trilogy on the African migrant’s experiences in America and draws his readers into the concourse of what amounts to an intriguing tale of human endeavor, enterprise, and aspiration that speaks to all.

When Count Crusoe Tutu leaves his native Ghana for the United States, he is full of love and admiration for his new home. After all, circumstances in Ghana force him to make desperate, even shocking choices as he is urged on to false conclusions about both his home and soon-to-be adopted country. Kwakye’s magisterial style is on ample display here as he charts a course from Accra to Boston and captures the yearning of the human spirit for self-improvement against a backdrop of false expectations as the US beckons seductively.

Typical of most of Kwakye’s oeuvre, this work must not be read overly literally, although the reader is presented with that choice. The expectation of a better life is mired in the reality of adapting to a new culture that can be hostile at times. The search for acceptance becomes as elusive as a mirage in many instances, pushing the migrant to self-doubt and an unanchored journey that wobbles on hopelessness. At the same time, in the cherished embrace of those that are welcoming, there is hope and encouragement to endure. Count Tutu realizes that his perceived romance with the US must be tested in the fire of compromises and hardships, such as the difficulties of finding employment, paying bills from meager means, and fitting in, all while expectations of the family left behind mount for him to help.

Kwakye impresses his reader with the vibrant power of description, from the flora and fauna of Accra to the landscape of Boston. We are treated in Accra to beans, plantains, onions, smoked tilapia, babies strapped to their mothers’ backs, and “the coarse crow of a passing hawk,” and in Boston to gentrified parts as well as “wooded neighborhoods so carefully manicured they appeared too idyllic for human habitation.”

Kwakye’s adroitness and sophisticated language evoke the colorful descriptions and allusions of reputable authors such as Hughes, Dumas, Shakespeare, Soyinka, Laing, Achebe, and p’Bitek, all undergirding this novel with erudition without surrendering its accessibility. At the end of the novel, Kwakye’s protagonist is shocked into the realization that no matter his own challenges, he is inevitably linked to the fate of those he has chosen to call his neighbors. In the end, The Count’s False Banquet masterfully blends old and new, familiar and unfamiliar, literary and literal, into a brilliant work of literature.

Dike Okoro

Northwestern University