Together Still by Yves Bonnefoy

London. Seagull Books. 2017. 133 pages.

London. Seagull Books. 2017. 133 pages.

Yves Bonnefoy, undoubtedly one of the major French poets of the last six decades, passed away in 2016, and Ensemble Encore, or Together Still, is, according to his publisher, “his final poetic work.” Actually, there is apparently a book of memoirs forthcoming in the next year; moreover, only about one-third of this “poetic work” is in verse forms, although Bonnefoy is well known for obscuring the boundaries between verse and prose just as he often confronts the representational issues that both vex and liberate the so-called sister arts of poetry and visual art.

Together Still is comprised of seven sections. Of the three most resembling prose, the longest is the final segment called “Perambulans in Noctem” (roughly “Walking into Night”), a collection of pieces from earlier in his career, unlike some of the verse sections whose composition is much more recent. The other two proselike sections come early in the collection. They are “Ursa Major” and “The Bare Foot”: the first an enticing sequence of seven pieces that involve a host of interlocutors, some or all or none of whom may be “Bonnefoy”; and the second a series of landscape fantasies, originating in some sense with Adam and Eve taking the initial barefoot step out of Eden. Both of these sequences may be more than first-time readers of Bonnefoy’s work are quite ready for. However intriguing their narratives, we are exposed here, in cryptic form, to ideas and problems that Bonnefoy has been facing throughout his career, not only as a poet but as an accomplished translator (of Shakespeare most notably) and a distinguished art historian.

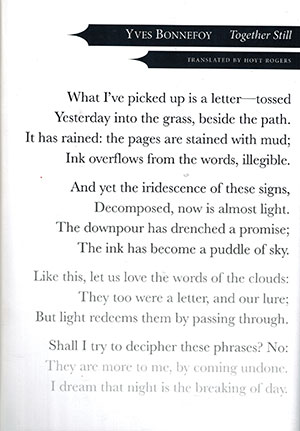

All readers will find the other four sections of this book illuminating and deeply moving. The opening section, which gives the book its title, is a kind of last will and testament addressed to his wife, daughter, old friends, former mentors, and also readers. While some of Bonnefoy’s verse can be quite challenging in its diction and imagery (because he believes both that language is visceral and materially at odds with much normal usage and also that imagery can deflect us from what he calls “presence”), “Together Still” is so translucent most of the time as to seem innocent of brushwork: “You raise the pages, / Fraught with signs, from this abyss / That is the thing still awaiting its name. // I remember. / The night had been that beautiful storm; / Then, for entangled bodies, / The bonding acquiescence of sleep. / At dawn, the child entered the room. / The morning meant we understood / That the fruits seen in the dreaming were real; / That our thirst could be appeased. And that light, / When it stands still, is happiness.”

Maybe that light is happiness, but light, in Bonnefoy’s personal aesthetic lexicon, is rarely so stable, so still. Elsewhere in this light-filled book we also glimpse “the thing still awaiting its name.” Translator Hoyt Rogers rightly calls the sonnet sequence “Together Music and Memory” Bonnefoy’s “finest.” “Briefwege” (or postal roads) recalls living in northern Germany near the Baltic and contains probably the best lyric in the book, “Briefweg, in Warbende.”

The sequence “Poems for Truphémus,” about a contemporary French painter who died just a year after Bonnefoy, also in his nineties, serves as the book’s epicenter. Its last poem recalls the work of the American painter Edward Hopper, also French inspired, who said of his late painting Sun in an Empty Room that “It was difficult to paint inside and outside at the same time.” Bonnefoy, who loved in Hopper a quality he coined “the photosynthesis of light,” concludes his poem: “The sun we woke to long ago . . . / How did we live? For your mirror, use / The window, the bed of this empty room.”

Kurt Heinzelman

University of Texas at Austin