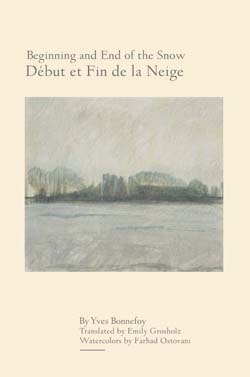

Début et Fin de la Neige / Beginning and End of the Snow by Yves Bonnefoy

Emily Grosholz, tr. Farhad Ostovani, ill. Lanham, Maryland. Bucknell University Press / Rowman & Littlefield. 2012. ISBN 9781611484588

This outwardly slight, paperbound volume opens to reveal an uncommon abundance: a series of exquisite poems by one of the most important poets in France today deftly rendered into English by a poet known for her delicate touch; an eloquent essay by Yves Bonnefoy himself, demonstrating his skill as a literary critic as well as a poet; and a charmingly direct meditation by the translator, Emily Grosholz, about her effort to create English equivalents of two Bonnefoy poems. As if that weren’t enough, there is the further pleasure of beautiful visual art in the evocative drawings of Iranian artist Farhad Ostovani that accompany the text.

This outwardly slight, paperbound volume opens to reveal an uncommon abundance: a series of exquisite poems by one of the most important poets in France today deftly rendered into English by a poet known for her delicate touch; an eloquent essay by Yves Bonnefoy himself, demonstrating his skill as a literary critic as well as a poet; and a charmingly direct meditation by the translator, Emily Grosholz, about her effort to create English equivalents of two Bonnefoy poems. As if that weren’t enough, there is the further pleasure of beautiful visual art in the evocative drawings of Iranian artist Farhad Ostovani that accompany the text.

The central unifying element of the first section of this book, “The Beginning and the End of Snow,” is the gracefully haunting metaphor of snow, a phenomenon that Bonnefoy says he began to consider more closely during winter walks through a forest in Massachusetts. “In Williamstown,” he remarks, “I learned what snow is.” The parallels between falling snow and the shifting, inchoate motions inherent in the movement of imagination or dream understandably compelled him, but so did the analogy to language the human impulse to eternalize the moment in a breathless swirl of words that then necessarily dissolve. Yet the memory of the moment and the brilliant flash of perception it produced lingers in the mind: “what promise / In this drop of water, this brief touch, since it was / Just for a moment, light!” And paradoxically, as in the movement of memory, the snow creates its own strange warmth like a secret script that imprints the present and allows us to “see / Leaves beneath the snowflakes, and warmth / rising from the absent soil like mist.”

The second section, “Where the Arrow Falls,” is an allegorical prose poem about losing one’s direction in life that is set in the landscape of the speaker’s childhood. As an adult wandering in the woods, he unexpectedly loses the path only a short distance from home and simultaneously suffers a dislocation of spirit. He is disconcerted to find that he has suddenly lost a sense of connection to the power of the word, which had previously stabilized his life. In that instant he imagines an encounter with an earlier, preternatural self and realizes that what he is feeling is simply the force of his lifelong solitude. “In fact, he has been moving forward among great mysteries for a long time. He was always alone”—as well as the stress of having to inhabit two worlds, the physical world and “another world,” perhaps best deciphered as that of the soul. Recovering the path and arriving back home, he briefly holds a lit match to one of his books. As he watches it burn for a moment, he considers the fragility of his own art in the face of mortality, feeling himself indelibly marked by the emblematic image of “this marriage of words and ash.”

Rita Signorelli-Pappas

Princeton, New Jersey