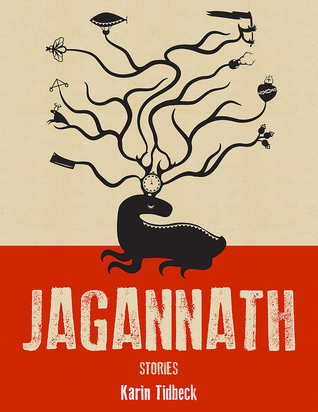

Jagannath by Karin Tidbeck

Tallahassee, Florida. Cheeky Frawg. 2012. ISBN 9780985790400

After reading the singular stories in Swedish author Karin Tidbeck’s first collection, what lingers in the mind is their deadpan strangeness. Tidbeck establishes this peculiar tonality in her stories’ first sentences and then never falters. “Beatrice” opens: “Franz Hiller, a physician, fell in love with an airship.” “Reindeer Mountain,” with “Cilla was twelve years old the summer Sara put on her great-grandmother’s wedding dress and disappeared up the mountain.” And “Cloudberry Jam” with “I made you in a tin can.” How could anyone not want to read on?

After reading the singular stories in Swedish author Karin Tidbeck’s first collection, what lingers in the mind is their deadpan strangeness. Tidbeck establishes this peculiar tonality in her stories’ first sentences and then never falters. “Beatrice” opens: “Franz Hiller, a physician, fell in love with an airship.” “Reindeer Mountain,” with “Cilla was twelve years old the summer Sara put on her great-grandmother’s wedding dress and disappeared up the mountain.” And “Cloudberry Jam” with “I made you in a tin can.” How could anyone not want to read on?

Tidbeck began publishing in Swedish in 2002. Since 2010 she has translated her work, including these thirteen stories, into English. Jagannath won the 2013 Crawford Memorial Award, given annually by the International Association for the Fantastic in the Arts to a new writer whose first fantasy book was published during the previous calendar year. Her one novel, Amatka (2012; Mix), awaits publication in English.

Tidbeck’s style is simple, almost minimalist . . . lest the slightest adornment destroy her stories’ delicate, subtle balance of weirdness and melancholy. But when she uses a figure of speech, it’s perfect: in a park, office workers on their lunch break “stretched out on the lawns, drinking the first summer sun like pale lizards.” In most stories, this stripped-down quality extends to characters: she rarely provides background about their acquaintances, hobbies, family . . . in some we don’t even know their names. Unemployed, with few if any friends, none close, they subsist in a social and cultural vacuum, their reality “a thin veneer behind which strange creatures move.” Yet some authorial magic brings them to life, and the often-

tragic outcomes of their encounters with the weird are deeply affecting.

Tidbeck seems able to adopt any storytelling mode. “Miss Nyberg and I,” “Herr Bederberg,” and “Cloudberry Jam” are slight vignettes. “Some Letters for Ove Lindström” consists solely of letters a bereft daughter writes to her dead father; “Brita’s Holiday Village” is the diary of the lonely, thirty-two-year-old would-be writer who finds that by entering the village she has crossed a boundary between reality and dreams. “Pyret” is a pastiche of an academic essay about “a mysterious life form . . . that likes to get close, cuddle, and sometimes even mate with [an] animal or person.” The title story—named, curiously, after a Hindu deity—is a richly detailed, straightforward, science-fiction adventure-cum-biomechanical nightmare.

For all their diversity, many stories resonate via shared imagery, events, and themes: family, birth, and the inexplicable appearance and/or disappearance of a mother. Tidbeck often links the latter to folkloric beings such as the vittra of northern Sweden, which appear at the shattering climax of “Reindeer Mountain.”

Except for the sardonic, visceral “Augusta Prima,” “Aunts,” and “Jaganath,” Tidbeck’s stories whisper. They offer hints at realities behind appearances but leave it to the reader to assimilate, to interpret. Careful manipulation of point of view compounds their controlled ambiguity and deeply estranging effect. If read slowly, one at a time, her stories reveal disquieting marvels unlike those of any other writer I’ve read. This collection is itself a marvel and whets the appetite for more.

Michael A. Morrison

University of Oklahoma