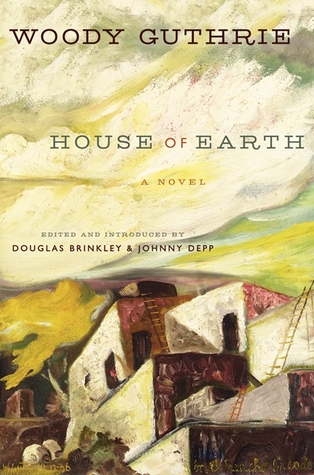

House of Earth by Woody Guthrie. Douglas Brinkley, ed.

Douglas Brinkley, ed. Johnny Depp, intro. New York. Infinitum Nihil / Harper. 2013. ISBN 9780062248398

It is customary when a reviewer has personal or business relationships with the author of a book she is reviewing to disclose those relationships. I consider myself one of Woody’s children: a leftist Okie poet who grew up working-class in a small town twenty-six miles from Okemah. Woody Guthrie’s politics, his writing, and his cultural roots are reflected in my own. All possible conflicts aside, though, House of Earth is a richly imagined, well-written novel that deserves a large readership.

It is customary when a reviewer has personal or business relationships with the author of a book she is reviewing to disclose those relationships. I consider myself one of Woody’s children: a leftist Okie poet who grew up working-class in a small town twenty-six miles from Okemah. Woody Guthrie’s politics, his writing, and his cultural roots are reflected in my own. All possible conflicts aside, though, House of Earth is a richly imagined, well-written novel that deserves a large readership.

Both of Guthrie’s previously published books of prose, Bound for Glory and Seeds of Man, are usually described as “quasi-fictional,” but House of Earth, while informed by his experiences in the Texas Panhandle, is Woody Guthrie’s only fully realized novel. House of Earth centers on Tike and Ella May Hamlin, a young couple eking out a marginal existence on a rented farm perched on the Texas Panhandle Caprock. Although they are living in the middle of a large landscape, the novel feels claustrophobic. The claustrophobia arises not only from the size of their eighteen-foot-square wooden shack but also from their oppressions: by the weather, by poverty, by the rich farmer they rent from, by the nearly invisible yet palpable American class system.

Midstory, the Hamlins fall to a worse status than before because their landlord refuses to rent to them any longer and expects them to work on shares. Tike narrates this as his “Fall,” from the ragged, precarious grace of being able to call a parcel of land his by virtue of a lease agreement to having “lost all of my hold on my whole world” and to “let myself fall so low, so damned low, as to end up being just another cropper!” The dream that keeps Tike and Ella May from utter despair is to buy a piece of land where they could build an adobe house, a house of earth that would stand against termites and the wind, a solid foothold from which they could dig their way out of poverty.

Guthrie takes quite a chance, narratively speaking, in this story: for the majority of the novel only the two main characters are in view—only one other person makes an appearance, late in the book. Instead of populating the novel with humans, Guthrie brings alive the Caprock environment and its animal inhabitants as characters. The environment as character and antagonist inflects House of Earth with the tropes of both realism and naturalism: the Hamlins are heroic in the sense that they are fighting a battle not only against the natural environment but also against their socioeconomic status. House of Earth is a truly radical novel but, as opposed to some naturalist and radical novels of the early twentieth century, you should read House of Earth not just because it’s ethically good for you but because it is a novel of great skill, linguistic beauty, and emotional honesty.

Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

Oklahoma City University