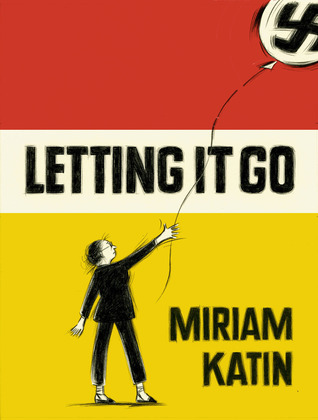

Letting It Go by Miriam Katin

New York. Drawn & Quarterly / Farrar, Straus & Giroux. 2013. ISBN 9781770461031

Seven years ago, Miriam Katin made an impressive debut with the publication of her first graphic novel, We Are On Our Own (see WLT, Mar. 2007, 66), a Holocaust tale of running, hiding, and escape. With Letting It Go, she confirms her place as a significant graphic novelist. A vivid storyteller, Katin manages to capture interior monologue and external narrative seamlessly with deft and elegant strokes, both verbal and pictorial.

Seven years ago, Miriam Katin made an impressive debut with the publication of her first graphic novel, We Are On Our Own (see WLT, Mar. 2007, 66), a Holocaust tale of running, hiding, and escape. With Letting It Go, she confirms her place as a significant graphic novelist. A vivid storyteller, Katin manages to capture interior monologue and external narrative seamlessly with deft and elegant strokes, both verbal and pictorial.

Her central character, Miriam, is a middle-aged, married Holocaust survivor and artist whose only son, Ilan, decides to live in Berlin and wants to become a Hungarian citizen, his right because Miriam was born in Hungary. This initiating incident is central to the tale, but it is in the details of the story that we find the surprise and delight in this work. An imagined catastrophe resulting from explosions of beautifully designed German products plugged into many American kitchen outlets leaves us with no doubt about the narrator’s fears. Nor is there doubt about her sense of humor. A meditation on procrastination cites Proust’s A la recherche du temps perdu and then has her wandering the apartment only to land in front of the refrigerator peering into a container thinking, “A la recherche des sardines perdus.” Katin wears her learning lightly, and in both word and image she conveys humor while revealing buried and not-so-buried fears.

There is also a fascinating shift in perspective embedded in the movement of her tale. One moment she tells her son that the ground of Germany is soaked with the blood of Jews after he tells her that Berlin is where art is happening; the next she goes to visit her mother, with whom she still speaks Hungarian, and is told by her that Ilan is just like her, running and never caring who is left behind. These shifts in perspective are remarkably fluid, made more so by the fact that there are no frames to these illustrations. A page of drawings swings from an interior thought to a conversation to a dream, from a ground view to an aerial, and from present to past. Yet so compelling is Katin’s narrative that the reader is fully engaged and never set adrift.

There is horror here, to be sure. On her first visit to see Ilan in Berlin, where he is living with his non-Jewish Swedish girlfriend, Miriam struggles between the comfort of modern Germany and the ghosts of the past. In fact, every time she spends a night in a German hotel, her body rebels in rather graphic ways.

Making peace with the past and reconciling memory with current reality is at the heart of Letting It Go. After traveling the difficult journey with Miriam, the reader is much richer for the experience and has an equally hard time letting it go. Katin’s remarkable work gets under the skin.

Rita D. Jacobs

Montclair State University