Don’t Mention This to Anyone: Poems and Prose Fragments of Life in the Punjab and Rug of a Thousand Colours by Tessa Ransford

Tessa Ransford. Don’t Mention This to Anyone: Poems and Prose Fragments of Life in the Punjab. Jila Peacock, ill. Edinburgh. Luath. 2012. ISBN 9781908373182

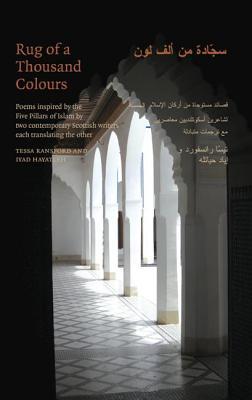

Tessa Ransford & Iyad Hayatleh. Rug of a Thousand Colours. Edinburgh. Luath. 2012. ISBN 9781908373243

In Don’t Mention This to Anyone: Poems and Prose Fragments of Life in the Punjab, Indian-born Scottish poet Tessa Ransford introduces the reader to her “Indian Self.” Celebrating her birth “among dark eyes,” she writes: “to have first found the world / in abundant India / is my life’s greatest privilege.” A mixed privilege, however: “Before I was ten I lived in eleven dwellings / and eleven more before I was thirty and three. / Twenty-two homes to live in and leave / in thirty years, and you ask me where I come from!” The reader glimpses where Ransford comes from as the poems turn into eyes, observing an immensely beautiful landscape stained only when the people living there are seen suffering. One sees a woman giving birth in the darkest corner of a room; mothers fighting poverty to rescue the lives of children; people celebrating Muslim Eid; rice being served on Christmas; snakes being killed as a ritual; and men and women sweeping not to clean a place but to let go of what happened previously and allow for new life.

The book includes numerous Urdu sentences in calligraphy, not unlike phrases on flashcards found in the pockets of tourists in unfamiliar cultures. Ransford is, however, a tourist in her own past in India and then later on in Pakistan, but she is a tourist with the “golden thread of poetry” inspired by her Indian self. In poetry, she acknowledges, “Joy is my element.” In poetry also she asks elegantly: “Must we turn our eyes away, / questions suppressed, opinions withheld? / Who is giving these orders? / Truth disobeys them.”

Nonconforming truths lead Ransford to the idea of Rug of a Thousand Colours, co-authored with Palestinian-Scottish poet Iyad Hayat-leh. An exile many times himself, he writes: “we leave the mire of the camp, / embrace a continuing diaspora.” Ransford and Hayatleh bring together Arabic and English, Islam and Christianity, and a brave book of poems. Separately, each poet wrote a poem inspired by the five pillars of Islam. They translated each other’s poems to English and Arabic.

Of prayer, one of the five pillars, Hayatleh takes refuge in that prayer is a home one can never lose: “there is only one language for prayer.” Ransford fights for a definition. She had prayed in many ways, at times of panic and need, but found out that “none of this is praying.”

Both poets agree that almsgiving, a pillar, is most fulfilling when giving of oneself. Fasting, another pillar, reveals multiple connotations in the inspired poems in this collection. To hunger for seeing those whom you love and not see them, as is the case with refugee poet Hayatleh, is fasting of a haunting kind. For Ransford, the deprivation of sharing, curiosity, and seeking knowledge is a grueling fasting.

This multicultural poetic coming together is a delightful new dimension that reveals how faiths, nourished with the gentle intent to understand, can make the world broader. Risking criticism of his writing poetry about Islam, a religion that has a deep yet not entirely embracing view of poetry, Hayatleh succeeds in maintaining a sensitive and thoughtful view all along, one that flowers into the larger spirit of the pillars embedded in the rituals. Ransford and Hayatleh’s poems possess a grace that honors the spiritual theme they explore.

Finally, was Robert Frost right when he stated, “Poetry is what gets lost in translation”? In the foreword to Rug of a Thousand Colours, David Finkelstein emphasizes that this collection “suggests quite the opposite.” There is evidence, however, that supports Frost’s view even in this excellent collection. For example, in translating Allahu Akbar, Ransford wrote: “Allah is great.” The Arabic word akbar means the absolute superlative, excluding the possibility of being great among other great beings, but rather greater than all beings—the greatest. Also consider the title word “rug,” sejjadah in Arabic. Sejjadah is a word constructed from the root verb sajada. Therefore a sejjadah is the rug where a worshipper places the head in complete submission to God during the act of prostration. It is a prayer rug, named with a spiritual intent, not simply a rug. Such details are lost in the translation. But if poetry ushers a dialogue and provides a meeting point to ask and learn, then what is lost in the translation is gained in the necessary cross-cultural conversation.

Ibtisam Barakat

Columbia, Missouri