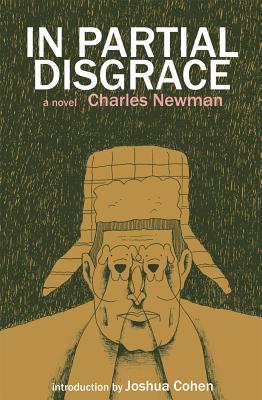

In Partial Disgrace by Charles Newman

Ben Ryder Howe, ed. Joshua Cohen, intro. Champaign, Illinois. Dalkey Archive. 2013. ISBN 9781564788160

To understand the mind of those who live in the veiled, history-bound, intellectually suicidal Crownlands of Cannonia, a country rising from foggy, boggy Marchlands upon which bloody stalemates were fought, one must follow two lines of thought. First, Heraclitus stated that no man steps in the same river twice, but in Cannonia one can step into the river “twice and twice and twice again,” for both the river and time are known to flow back and forth. This Joycean “commodius vicus of recirculation” forms the plot’s engine. Second, discourses combine European philosophical undertakings with an old joke about a dyslexic: the Cannonians spend time contemplating Nature, Man, and Dog.

To understand the mind of those who live in the veiled, history-bound, intellectually suicidal Crownlands of Cannonia, a country rising from foggy, boggy Marchlands upon which bloody stalemates were fought, one must follow two lines of thought. First, Heraclitus stated that no man steps in the same river twice, but in Cannonia one can step into the river “twice and twice and twice again,” for both the river and time are known to flow back and forth. This Joycean “commodius vicus of recirculation” forms the plot’s engine. Second, discourses combine European philosophical undertakings with an old joke about a dyslexic: the Cannonians spend time contemplating Nature, Man, and Dog.

The story of Cannonia and a few of its people is a collection of fragments written by gnarly gamesman Charles Newman, who worked for more than twenty years on the project. He mired himself in research, merged real and pseudo-history, and intended a tripartite Cold War novel of suspense. This is the unfinished result of that massive goal. Stylistically, Newman wrote himself onto a ledge where his only option was to leap into a postmodern void.

Enter Rufus Hewitt, by parachute. This counterintelligence operative and co-narrator of the story descends to the hermit kingdom in order to write of Iulus, who becomes inadvertently, upon the discovery of his archives, the first great writer of the twenty-first century. The action takes place at Semper Vero, the estate originally inhabited first by Iulus’s grandparents, who arrived with nothing but the bust of Erasmus, suggesting that Iulus inherited the family traits of social criticism and humor. Here, Iulus lives with his parents: his father, a dog whisperer with a fondness for a painting titled White Poodle in a Punt, and his mother who, when Iulus brings home an unsatisfactory school report, merely smiles and draws the document across his palm leaving a paper cut.

The dog days of Cannonia have arrived, but in Cannonia all days are dog days. Dogs are “a kind of theme in a larger drama over which we had already lost control.” Iulus spends hours documenting the conversations around attempts of his father to train the unruly dog of a visiting professor. Luckily, Cannonians are loquacious, and Iulus captures Sternean capriccios of passionate opinions spiced with memorable aphorisms: “Art is something which happens between accident and its criticism”; “If you cannot be truthful, then at least be deep”; “The best pet is a pet idea”; and “Each hour dooms Man, the last one kills him.”

Cannonians say, “To be well hidden is to live well,” so just who hides from whom in this spy novel? Rufus uses counterintelligence to document the agent Iulus. Iulus is the independent operator, possibly CIA, who documents everyone else. By the end of the novel, Iulus has disappeared and Rufus is left to comb Iulus’s extensive archive in search of the story. How sure is he in trusting his narrator? Not sure at all. He says, “This is rather like asking the question: can one trust a sonata?” Newman’s writing is as fabulous and convoluted as Cold War rhetoric, which the author describes as a “bizarre sideshow of poetic illusions.” This is a novel built upon a cloak of secrecy that continually flashes an interior lining of dazzling shot silk.

Christopher Willard

Calgary