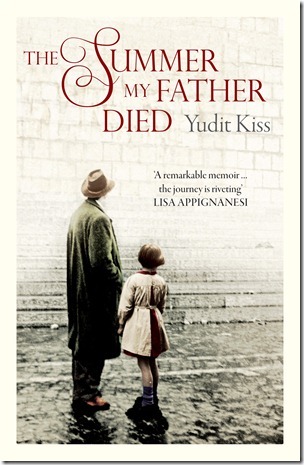

The Summer My Father Died by Yudit Kiss

George Szirtes, tr. London. Telegram. 2012. 268 pages. ISBN 9781846590948

Yudit Kiss (born Judith Holló) is a Hungarian-born economist based in Geneva. She grew up in Budapest during the decades known as the “Kádár Era,” named after Communist Party leader János Kádár, who experimented with the pseudo-consumerist one-party system known as “goulash Communism.” The Summer My Father Died is a colorful chronicle of her attachment to and conflicts with her father, a staunch Jewish member of the Communist Party and ardent believer in the future of Marxist-Leninism.

Yudit Kiss (born Judith Holló) is a Hungarian-born economist based in Geneva. She grew up in Budapest during the decades known as the “Kádár Era,” named after Communist Party leader János Kádár, who experimented with the pseudo-consumerist one-party system known as “goulash Communism.” The Summer My Father Died is a colorful chronicle of her attachment to and conflicts with her father, a staunch Jewish member of the Communist Party and ardent believer in the future of Marxist-Leninism.

Having read memoirs of people who resisted totalitarian governments in either their Nazi or Soviet edition, it is educational to learn something about the life and problems of a person born into a family that was among the prime benificiaries of the Communist regime. Yudit’s father, who had suffered persecution as a Jew during World War II, nurtured the belief that the new society managed to destroy old prejudices by creating equal conditions for all its citizens and, at the same time, for many years enjoyed the privileges of a party functionary. For him and his family, the Hungarian uprising of 1956 was clearly a “counter-revolution,” and even the Prague Spring of 1968 was a betrayal of “existing Socialism.”

When Yudit as a young Hungarian student visited Prague with some friends soon after the Soviet intervention, she was baffled by the hostile reception of the sullen natives. Communist indoctrination, which hardly worked for my generation, must have been very strong in some families of “Kádár’s children”; Yudit confesses, “I only learned about what really happened in Czechoslovakia in 1968 much later from a Greek friend.” It was a shock for her to learn the truth, but it also started a process of opening up, distancing herself from her father’s beliefs. During the story the father is slowly transformed into a tragic figure: while his daughter grows up and embraces “Western” (liberal democratic) ideals, with the change of regime in 1990, he not only loses his power base but also his ideological certainties, dying as a sad, old man who had wasted much of his life.

Yudit Kiss’s story is structured in a mosaic-like manner: personal reminiscences about her father and her family (including a vicious non-Jewish grandfather) alternate with snippets of foreign travels and accounts of books read. It is particularly interesting to learn how she embraces her almost forgotten Jewishness during a visit to Kraków and what she thinks about the “ethnic cleansing” perpetrated by the Serbians during the Bosnian War, but a conversation with a Gypsy boy about Seneca in the Budapest metro and another one with a Spanish anarchist who recommends to Kiss the reading of Arthur Koestler are also worthy of attention. The English critic who called this book “a remarkable memoir” is altogether right, thanks, among other things, to its very fluent rendering into English by the prizewinning Hungarian-born English poet George Szirtes.

George Gömöri

London