Seeking the Light through Literature

Religion is at its best when it becomes a countercultural force; when it has no power, only influence, no authority except that which it earns, no claim to people’s attention other than by the way it creates values that cannot be found elsewhere. It is then that it loses its perennial tendency to corruption and becomes again what it once was—a startling new voice, redeeming us from our loneliness, framing our existence with meaning, and teaching us to remember what so much else persuades us to forget—that the possibilities of happiness are all around us, if we would only open our eyes and give thanks.

—Rabbi Jonathan Sacks

The word mythos comes from the Greek word which means to close the mouth or close the eyes. Mystery and mysticism come from the same root. . . . We approach this kind of knowing in art. . . . You’re being pushed beyond the rational thoughts and distinctions into a silent intuitive space.

Theology is poetry. A poet spends a great deal of time listening to his unconscious, and slowly calling up a poem word by word, phrase by phrase, until something beautiful is brought forth, we hope, into the world that changes people’s perceptions.

Religion is not about accepting twenty impossible propositions before breakfast, but about doing things that change you. It is a moral aesthetic, an ethical alchemy. If you behave in a certain way, you will be transformed.

—Karen Armstrong

The human heart abhors a vacuum. With organized religion losing ground, all sorts of substitutes rush in to fill the god-shaped hole. One particularly effective and time-honored balm for the aching human heart is literature. For some, poetry is how we pray now. In these skeptical times, there still exists an Absolute Literature, in the coinage of Italian writer Roberto Calasso, where we might discern the divine voice. Such pre- and postreligious literature shares aims and concerns similar to belief systems: sharpening our attention, cultivating a sense of awe, offering us examples of how to better live and die—even granting us a chance at transcendence.

Mysteriously, certain strains of literary art are capable of using words to lose words—ushering us to the threshold of that quiet capital of riches: Silence. It is, after all, in silent contemplation that difficulties patiently unfurl and entrust us with their secrets. By deepening our silences, such ethical literature allows us to overhear ourselves and can lend us a third (metaphysical) eye. We are able not only to bear witness to the here and now but, past that, calmly gaze at eternal things, over the head of our troubled times, in order to try and understand our spiritual condition (where we’ve come from and where we’re heading).

One particularly effective and time-honored balm for the aching human heart is literature. For some, poetry is how we pray now.

Currently, in our fractured world, beset by so much physical suffering and political turmoil, as a kind of (unconscious?) corrective, more people are reading and writing literature that addresses the life of the spirit, overtly or otherwise. One manifestation of this renewed spiritual hunger that is being met by literature is the recent publication of a major new anthology, The Poet’s Quest for God: 21st Century Poems of Faith, Doubt and Wonder (Eyewear, 2016), featuring over three hundred contemporary poets from around the world and of great value (as the jacket blurb indicates) “to those for whom poetry has become a resource or replacement for faith-bound spirituality.”

Likewise, more literary-spiritual oases are appearing in the desert of popular culture to slake the great thirst of seekers. Among the ones I’m aware of, and turn to for sustenance and inspiration, are edifying podcasts such as Krista Tippett’s On Being and Godspeed Institute, or interfaith literary journals such as The Sun, Parabola, Tikkun, Tiferet, Sufi, and many others.

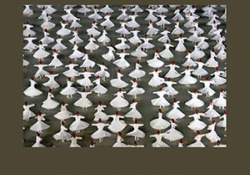

But, since we cannot step into the same river twice, what does a return to religion look like? There are poets, writers, and artists, in this special issue and beyond, who pursue direct paths to God through their art. And there are readers, myself included, who study the lives and utterances of traditional saints and mystics for moral guidance and uplift. For example, in Brad Gooch’s remarkable new biography, Rumi’s Secret, where the celebrated mystical poet and world he lived in (around eight hundred years ago) come to life, we develop a deeper appreciation of why this Muslim saint matters to us so much at this historical moment.

Gooch, in conversation with ambitious Rumi translator Jawid Mojaddedi, quotes Mojaddedi as saying to him: “Rumi resonates today because people are thinking post-religion. He came to see mysticism as the divine origin of every religion.” This is a subject that Mojaddedi further unpacks in his illuminating piece featured here, “Following the Scent of Rumi’s Sufism in a Postreligious Age.”

Coleman Barks, regarded as one of the great popularizers of Rumi in English, concurs: “I do believe that Rumi found himself going beyond traditional religion. He has no use for dividing up into the different names of Christian and Jew and Muslim. It was a wild thing to say in the thirteenth century, but he said it, and he was not killed.”

Nowadays, there is also a more ambiguous literature (as well as audience) that finds it needless to name their nameless yearning and sees no contradiction in drawing on different traditions to make a patchwork quilt of their inchoate longing. This peculiarly modern pilgrim, unencumbered by dogma, is unembarrassed to treat organized religions as an archaeological site to be excavated for durable ruins—unearthing fragments of Beauty, Grace, Wisdom wherever they might find them and leaving behind what does not resonate spiritually.

Belief, in the midst of chaos, remembers the indestructible world.

In such literature that is not directly religious, all sorts of spirits are invited, random relics thrown into the spiritual pot to prepare a nourishing bone broth. Amid culture wars dominating the headlines and airwaves, prayerful prose or poetry and mystic art grant us the opportunity to share Good News, or to make a joyful noise. One way of doing so is by giving thanks, even in the midst of suffering, or “try[ing] to praise the mutilated world” (Adam Zagajewski). In a hymn of a poem, “Brief for the Defense,” Jack Gilbert urges:

We must have

the stubbornness to accept our gladness in the ruthless

furnace of this world. To make injustice the only

measure of our attention is to praise the Devil.

Belief, in the midst of chaos, remembers the indestructible world. And we are fearless once we recall that we are also deathless. Belief also teaches us to deeply trust, in spite of appearances, in the innate and inexhaustible goodness of life, and how we might contribute to it by caring for our souls. Instinctively, out of self-preservation in the encroaching darkness, we seek out the light with greater urgency—recognizing the necessity for transformation, reevaluation of values, evolution . . . We are called to sanctify our days, in the phrasing of Kahlil Gibran:

Your daily life is your temple and your religion

Whenever you enter into it take with you your all.

Thus, literature in the service of belief, some of which we have gathered here, though mindful of other disciplines, is also shrewdly aware of their inadequacies—how the consolations of psychology, philosophy, science, even language cannot quite address the mysteries of the human heart. Mystical art addresses a mute center in us, initiating us into hardly communicable secrets, numinous states of being and a knowing (gnosis) at the very limits of our self or ego.

Through myth and parable, the defiant muse instructs us in the art of being present and then how to vanish without a trace. More variations on the time-honored themes: loss, ecstasy, home, how to live with our unquenchable thirst, using odes to joy and manuals of love. Yes, at the essences of these meditations is always love. May this special issue lead us to offer ourselves up to the world, to be used in loving service.

Fort Lauderdale, Florida