They Will Drown in Their Mothers’ Tears by Johannes Anyuru

San Francisco. Two Lines Press. 2019. 278 pages.

San Francisco. Two Lines Press. 2019. 278 pages.

Johannes Anyuru turns sturm und drang into elegant speculative fiction in his novel They Will Drown in Their Mothers’ Tears. Published in Sweden as The Rabbit Yard, the terroristic time-traveling tome won the 2017 August Prize for Literary Fiction. Momento Film acquired movie rights. Saskia Vogel (whose own novel Permission debuted recently) translated it into English, maintaining Anyuru’s poetic approach, infusing despair with hopefulness.

He begins with two girls on old tire swings, then segues to a comic book store in Gothenburg, Sweden. Owner Christian Hondo will discuss free-speech limits with Göran Loberg, who has published blasphemous caricatures of the Prophet Mohammed (recalling 2015 events at Charlie Hebdo in Paris).

Bearing ammunition, Nour, Amad, and Hamin enter Hondo’s set to become Daesh martyrs. Nour, a young woman desperate to remember her past, thinks she’s from Gothenburg but isn’t sure. Hamin performed a ceremony marrying her to Amad. Nour in Arabic means “light,” an Islamic name for God, a Qur’an chapter, and a recurring theme here.

Nour, wearing a bomb vest, begins livestreaming via cell phone as instructed, assuming participant/observer roles. Anyuru critiques journalism, taking on “the media machine.” Noting how the camera isolates, he ponders weaponization of the gaze—akin to University of Pennsylvania professor Barbie Zelitzer’s book About to Die: How News Images Move the Public, but Anyuru’s slant is literary.

A moth appears. Nour grasps at memory, doubting her name. Is she from the future or the past? Answers vanish.

Location shifts to a high-security criminal psychiatric clinic near Gothenburg, time shifts ahead two years, and voice shifts to a well-known author visiting a patient—the young female terrorist. Claiming she’s Annika Isagel, not Nour, she hands the unnamed writer a stack of papers, her story’s first chapter. He continues to visit, she continues to write, and he starts to believe her account—and his role in it.

Annika forecasts a different future she wants to prevent: citizens are labeled either “human” or “animal.” Those not Swedish enough live in a ghetto called the Rabbit Yard. Crusading Hearts (suggesting the Proud Boys) patrol for refugees: the nerve of these people, thinking they could come here and be Swedish.

Annika was reeducated at a secret prison in Belgium. No wonder memories elude her. Anyuru writes movingly about torture rooms, fostering empathy as did Viet Thanh Nguyen in The Sympathizer and Adam Johnson in The Orphan Master’s Son.

Anyuru establishes the passage of time, another theme, by introducing next-generation Apple products (“the iWatch 14 was released that year”) and mentioning pop star Oh Nana Yurg’s latest song, hairstyle, or clothes. Annika’s flashbacks recall her friendship with a girl named Liat—how they idolized Oh Nana Yurg.

How are young people radicalized? Terrorist, by John Updike, and The Garden of Last Days, by Andre Dubus III, attempted answers. Anyuru describes adolescent development in fluent teenage vernacular. Who am I? Is that quest biological or sociological? Including peer groups and entertainment icons in identity formation, he reinforces Lawrence Kohlberg’s cognitive approach while underscoring the role of social conditions à la Albert Bandura.

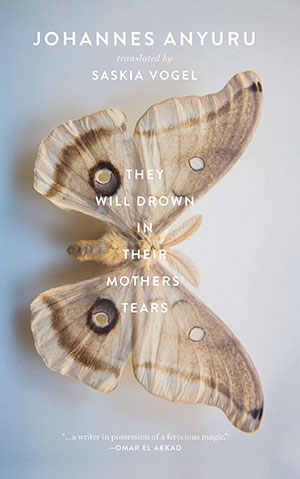

Anyuru luminously combines the motifs of light and moths as they flit through his pages. Designer Gabriele Wilson used a cover photo by Jasper James of a male polyphemus wild silk moth (ID’d for me by entomologist Mike Quinn). This particular specimen, faded over time from light exposure after mounting, thus becomes a striking metaphor.

Consider Polyphemus, the one-eyed cyclops of Greek mythology who imprisoned Odysseus. Moths symbolize slow, invisible destruction of valuables, be they wool sweaters or society itself. Some cultures associate moths (particularly white ones) with death, while others (Colombia/Venezuela’s Wayuu) perceive ancestral messengers or protective angels. Anyuru’s mariposa nocturna represents a conundrum: moths are drawn to light, which ultimately consumes them. Odysseus blinded Polyphemus. Hamin and Amad spun a cocoon around Nour.

Anyuru narrates a horrific story in graceful prose. He’s captured the zeitgeist in this Swedish saga, creating a literary outlet for global mourning strengthened by his experience as a poet, playwright, novelist, and essayist. The world faces an expanding refugee population with no idea which nationality to claim: Who am I? “People like us, we have no power,” writes Anyuru.

This scenario feels more contemporary than futuristic, layered so subtly that the full impact doesn’t hit until several days after finishing the book. What will last? Could society collapse? Can we learn to live together?

Johannes Anyuru plants hope in They Will Drown in Their Mothers’ Tears. And we need it.

Lanie Tankard

Austin, Texas