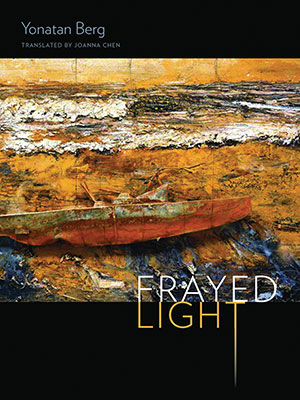

Frayed Light by Yonatan Berg

Middletown, Connecticut. Wesleyan University Press. 2019. 92 pages.

Middletown, Connecticut. Wesleyan University Press. 2019. 92 pages.

The Hebrew language has a special term for the process of becoming less religious, which translates as “to revert to a mode of questioning” (Lahzor Be She’ela). It is a term that expresses an awakening, a skepticism about what has been, until now, believed unconditionally, an opening of what was considered closed. This frame of mind forms the backdrop of Frayed Light, the first translated collection of work by the Israeli poet and novelist Yonatan Berg.

“In conversations I cannot explain myself,” Berg writes in “Letter to the Reader,” the opening poem of the collection, and proceeds to interrogate and explore, through lyrical form and language, the curious and complex path his life has taken thus far. Berg, born in 1981 to a Russian immigrant father and Israeli mother, was raised in Psagot, a religious settlement in the West Bank that borders on the Palestinian city of Ramallah.

After receiving a religious education, he served as a combat soldier in the IDF, a period that included the last war in Gaza, and an outbreak of post-traumatic stress syndrome. What followed was a long process of self-searching through travel (in India and South America), study (he is an accredited bibliotherapist), and writing. In 2012 Berg was awarded the prestigious Yehuda Amichai Prize, the youngest poet to receive it. His first novel, Five More Minutes, received the 2015 Ministry of Culture prize. Several of his poems, translated by Joanna Chen, have appeared in English-language journals, and the collection was recently singled out by the New York Times “Globetrotting” column as an anticipated book of 2019.

These, then, are the dry details, but Berg’s life, as it emerges through the lines of his interrogative, image-filled poetry, features as a narrative from which he is ultimately driven to escape and, after long wandering, return to, wizened and changed, seeing the deeply conflicted setting of his youth with new eyes. In “Ramallah through the Window of a Bus,” for example, he recalls: “Travelling through Ramallah, on our way to school – / early morning, the city preparing / for the day – stores just opening, steam / rising thinly from freshly made coffee.” He later concludes, “Years later, I would be lying if I said / there was no contempt back then, no / creeping fear, but it came from outside, / never from within.”

It is with that same sense of soul-searching that Berg revisits his long journey of transformation in “Distance”:

“Do you remember returning from the yeshiva, / the path leading up to the house, the stairs, and all the times / you climbed them in uniform, the gun bouncing on your back, the stench of oil, all the times you cursed out loud, / having nothing more appropriate to say, before death.” And later reflects at the close of the poem: “Years afterward I danced under the moon, naked and hallucinating, / Goa, Gorkarna, Varanasi, Taganga, Itraka, Ika, Banyus: / a series of pledges in the distance. / On the way home, it turns cold. / A single car violates the Shabbat. Something drops, disappears.”

The longest section of the collection is devoted to a cycle of poems that deal with biblical, historical, and literary figures, which he explores through the lens of our current time, and his own life experience, in deeply personal ways. His poem inspired by the mythical tower of Babel, for example, is a meditation on the experience of the immigrant. “Nothing prepares you / for the twilight; / you revisit somewhere that does not exist / and all of a sudden you’re in the right place.” It’s noticeable that Berg has chosen many female figures, both biblical, such as Sarah and Hagar, and modern personages, such as Rosa Luxemburg and Hannah Arendt, as his subjects. In these poems, he projects himself into the soul of these protagonists, as though aiming for as close and sympathetic an identification as possible.

Rendering poetry from one language to another is painstaking and arduous, and Joanna Chen’s translations are such that the poems retain their subtlety and power without feeling translated at all. Often it is the simpler ones that present more rigorous challenges, as in the first stanza of “Epilogue,” the final poem of the collection: “The lake is revealed where the sky withdraws. / Twilight lifts, water coalesces / into an opaque gleaming rock. / November. Through naked trees, / through village houses / kitchen windows are illuminated.”

Frayed Light offers readers both a poetic journey and new ways in which to think about the tension between innocence and experience, while enacting what it means to hold one’s deepest beliefs up to an inquiring light. Poets must work within the limits of language, yet one senses in these poems that what Berg is seeking in his explorations is a bridge, an intimacy that will overcome barriers of language, religion, and otherness itself. “I apologize to each and every one of you,” he writes at the conclusion of “Letter to the Reader,” “that I cannot reach out / to ease your pain . . . / That being the case, / this letter becomes one blurry trail / of what, at day’s end, / I really wanted to whisper in your ear.”

Janice Weizman

Rehovot, Israel