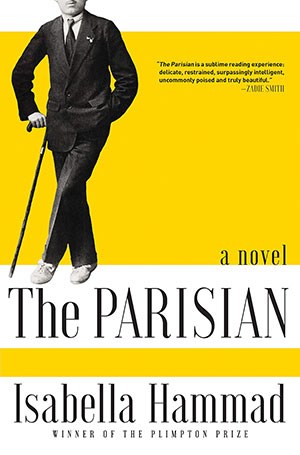

The Parisian by Isabella Hammad

New York. Grove Press. 2019. 576 pages.

New York. Grove Press. 2019. 576 pages.

Most novels about Palestine focus on the events following the Nakba (the catastrophe, in Arabic) of 1948. Isabella Hammad chooses to focus on the neglected pre-Nakba time period, before Palestinians became defined by Israel in the global media. In the process, she gives us literature that, to quote another novelist of the diaspora, Hala Alyan, “can play a powerful role in emotionally translating political events.”

The book tells the story of Midhat Kamal, the son of a well-to-do Palestinian textile merchant who, in 1914, sends his son off to Montpellier, France, to study medicine and to escape conscription into the Ottoman army on the eve of World War I. We follow Midhat (whose character was inspired by the author’s own great-grandfather) through the triumphs, revelations, and disappointments of his years in France and then his reluctant return to the city of his birth, Nablus, the setting for the last two-thirds of the book and itself a fascinating character. Throughout, this bon vivant is at the sidelines of the dramatic action of the day (the Great War, the beginnings of Palestinian resistance) but continues to grapple with his feelings of alienation, with the difficulty of defining himself while those around him insist on doing the defining, and with what little control he really has over his own fate.

A vast cast of characters joins Midhat, and the author deftly handles them all. Betrayal—between nations as well as individuals—recurs throughout, but redemption is not always withheld, and other balancing acts rotate into view: between knowledge and power, superiority and objectivity, freedom and responsibility. Several characters have their worldviews abruptly changed, and reflecting on their previous assumptions and their shifts in perception brings humility and, perhaps, a spiritual expansion. Midhat, an innocent and somewhat self-absorbed soul, is not immune: “It occurred to Midhat that a tragic story told quickly might contract easily into a comedy, and without the measure of its depths make the audience laugh. . . . [He] was thinking about the way his own charade might be told after he was dead, when he no longer held the reins on his memories, and they galloped off into the motley thoughts and imaginations of others.”

This is a lovely tale of a gentle person in ungentle times and a wonderful reminder of the great variety of Palestinian people and the wounds they have had to endure.

Jehanne Moharram

Norman, Oklahoma