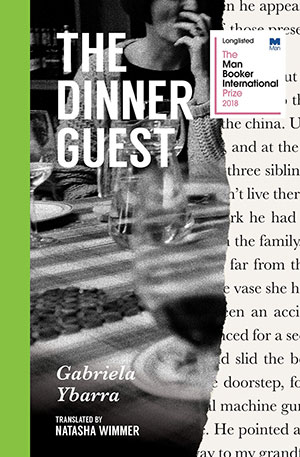

The Dinner Guest by Gabriela Ybarra

Oakland, California. Transit Books. 2019. 150 pages.

Oakland, California. Transit Books. 2019. 150 pages.

Gabriela Ybarra grew up in death’s shadow. Before she was born, her grandfather was kidnapped and executed by Basque separatists. When she was young, her father received a bomb in the mail, and in 2004 her mother was diagnosed with cancer. Ybarra weaves all three of these experiences into a multifaceted narrative of death, absence, and fear in her debut work of autofiction, The Dinner Guest.

Ybarra’s novel opens with a bang. Her grandfather is kidnapped from their family home in Neguri. Ybarra explores this event as she learns about it years later, piecing together critical and often conflicting details from friends, family, and investigative research, to address not only her family’s experience of death, grief, and fear but also her own experience of absence, silence, and confusion. It is a narrative of conflicts, near-miracles, and ultimate tragedies that makes for an explosive and compelling read.

The novel shifts in its second part, as Ybarra recounts her mother’s battle with colon cancer and her personal realizations regarding death and mortality. Each scene is reconstructed in striking detail, and Ybarra’s reflections combine the quotidian and the extraordinary in brief, elegant prose. She gives the same intimate narration, now quieter in tone, and her unabashed presentation advances the story and draws connections between violence and inevitability in her family.

The Dinner Guest is an exercise in opposites. Where Ybarra’s grandfather’s kidnapping is sudden, violent, public, and discordant, her mother’s diagnosis and treatment are slow, private, and consistent with the status quo. Where her grandfather has priests who would divine his location, her mother has doctors who guarantee her recovery. And where Ybarra’s family grieves together for her grandfather, Ybarra’s siblings are spread out, and she must care for her mother on her own. It is this opposition from which Ybarra draws her own personal narrative and insights as she struggles to reconcile the distant and fragmented story of her grandfather with the immediate and all-too-coherent reality of her mother.

English-language readers are also rewarded with this translation, as Natasha Wimmer skillfully captures Ybarra’s precise, compact prose. Wimmer stays true to the language of the book and conveys not only the words but the sensation of Ybarra’s straightforward sentences into English. As a result, readers can readily appreciate Ybarra’s free recollections of loss and acceptance. It remains a moving narrative, with a balanced, serene perception of death and the lives that shape it.

T. Patrick Ortez

University of Oklahoma