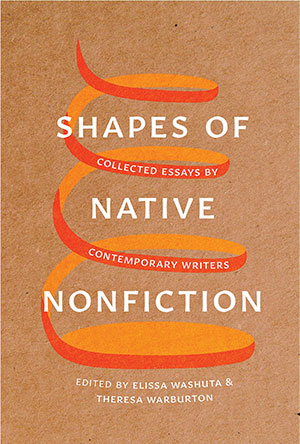

Shapes of Native Nonfiction: Collected Essays by Contemporary Writers

Seattle. University of Washington Press. 2019. 266 pages.

Seattle. University of Washington Press. 2019. 266 pages.

The best aspect of Shapes of Native Nonfiction: Collected Essays by Contemporary Writers is its intrinsic anthological quality. This anthology of indigenous writers features one or multiple pieces from twenty-seven Canadian and US authors, a veritable feast of First Nations and Native American writers that readers may otherwise never have discovered. This is not a collection of instantly recognizable literary rock star names—Joseph Boyden, Joy Harjo, David Treuer, Louise Erdrich, Sherman Alexie, Linda LeGarde, Natalie Diaz, and the newest addition to the canon of bright Native writers, Tommy Orange, are conspicuously absent—which leaves this fan of Native literature curious. Still, this book serves up plenty of new discoveries.

Consider Stephen Graham Jones’s essay, “Letter to a Just-Starting-out Indian Writer—and Maybe to Myself.” This essay could serve as a summary for this book’s intent and of expectations of indigenous literature overall. This piece asks heavy questions: What topics should we expect to find in an anthology of Native writers? How should we expect them to write?

The publishing industry will package Native writers as “exotic,” Jones warns. He also instructs: “Don’t let people shame you about not being an expert on your own culture,” and “You don’t have to be able to define what an Indian is in order to write ‘Indian.’ Putting a definition on us, that’s playing their game.”

These authors ask when exactly is it okay to stop talking about the fact that their people suffered genocide at the hands of whites for hundreds of years and that Western corporations continue to desecrate the land and rights of indigenous people today from Canada to Chile. They talk about trying to hold onto their traditions yet simultaneously progress. They are not writing for the acceptance of a white audience but for all the judging of and by each other and the lack of identity they sometimes feel as individuals.

Deborah A. Miranda’s “Tuolume” is a grueling, haunting personal narrative about generations of her family trying to make peace with itself and other family members. Her unwavering voice arrests readers from the start. This masterful storyteller can describe three generations in a breath: “My father was silent. I do know that. He was stunned by the beauty of that place, the taste of the wet air on his tongue, same air of his first breath, when he emerged from his mother’s womb nearly forty-four years before. Stunned by the song of water, the explosive greens of leaves and pine needles, the scent of life.”

Just as Hemingway could tell a story in six words, Terese Marie Mailhot exhibits equal talent in sentences in “I Know I’ll Go”: “Once, I packed my bags, mimicking my mother,” and “He promised me he would stop and then weeks later he left.”

Other writers to look for in this anthology include Tiffany Midge, whose fiery, aggressive diction could be used in warfare; Eden Robinson, who serves up a humorous take on dating other Indians; and Natanya Ann Pulley, who places readers at her family’s Thanksgiving dinner table when she was a child in “The Trickster Surfs the Floods.”

This book is not without its problems. Editors Elissa Washuta and Theresa Warburton may have tried too hard to draw a connection between making baskets and writing literary nonfiction. “Just as a basket’s purpose determines its materials, weave, and shape, so too is the purpose of the essay related to its material, weave, and shape,” reads the back-cover copy, which mirrors an unwieldy introduction by the two academics. They divided the book into parts with names such as “coiling” and “plaiting.” While it manifests as academic artifice more than actual structure, though, it doesn’t necessarily detract from the content within.

Academic literary qualities such as experimental essay types and the abundant racial/gender subject matter indicative of the early twenty-first-century zeitgeist make this a likely tome for the classroom. Readers who stick to Shapes despite periodic inaccessibility, however, will discover several works exhibiting lyrical and rhythmic mastery and gorgeous craft worth rereading multiple times.

Nichole L. Reber

Chicago