Translation’s Trends and Blind Spots: An Interview with Elisabeth Jaquette

In this new feature, Veronica Esposito interviews emerging translators who are changing the way we read world literature and beginning to reshape the translation field. While opening bookstores, leading national translation organizations, establishing local translation communities, and pioneering new forms of collaboration, these translators are finding and translating groundbreaking literature. In these pages throughout 2020 and online each month, Esposito explores what they've been up to, how they see their efforts as building up the future of the field, and, more generally, where the field is going. How is the literature that we read and publish changing as they continue to translate new books and work with new presses, and what might the future of translation look like?

Elisabeth Jaquette is a translator from the Arabic and executive director of the American Literary Translators Association (ALTA). Her book-length translations include The Queue, by Basma Abdel Aziz (WLT, March 2017, 56–59); Thirteen Months of Sunrise, by Rania Mamoun; The Apartment in Bab el-Louk, by Donia Maher; The Frightened Ones, by Dima Wannous; and Minor Detail, by Adania Shibli. She has been shortlisted for translation prizes and has received institutional support from a number of prestigious organizations. I spoke with her about her role as judge of the National Book Award’s translation prize, how instutions such as ALTA can better support translators, and what she would like to see more of from the translation community in the future.

Veronica Esposito: As executive director of the American Literary Translators Association (ALTA), you’re at the head of one of the most important institutions in the US translation world. What has ALTA been doing to be at the forefront of change in translated literature?

Elisabeth Jaquette: ALTA has long been a cornerstone of the literary translation world because of how it has recognized the importance of community. ALTA’s annual conference provides a space for translators to gather in person—something immensely valuable for a field comprised of individuals who are scattered across the country and working in isolation. In my eyes, ALTA’s Emerging Translator Mentorship Program, founded by Allison Charette in 2015, represents some of the most exciting work we’re doing. The program is designed to support emerging translators by pairing them with an established translator, to work together over the course of nine months. In 2019 we offered a record seven mentorships: in Arabic, Catalan, Korean, Russian, Chinese, and one non-language-specific mentorship.

Esposito: As a translator, you’ve published with some of the leading presses: Melville House, Comma Press, Darf, Harvill Secker, Fitzcarraldo, and New Directions. What practices have you observed with these presses that have helped them stay at the forefront of the translation world?

Jaquette: Listen to translators! That’s something that all these presses do well: they listen to translators when it comes to acquiring titles; they involve translators in the full life of the book, from asking for input on the cover to involving them in events. Another element that helps these presses stay at the forefront of literary translation is their engagement with the books on a structural editorial level. Generally speaking, the US and UK have a more rigorous editorial tradition, and so for many books from Arabic, the first edits the book sees are at the translation stage. The best editors I’ve worked with at these presses have been willing to do that in a collaborative, sensitive, consultative way.

Esposito: Speaking of listening to the translators, you were a judge for the 2019 iteration of the recently reinstated National Book Award in Translated Literature. It’s done an admirable job of including translators in its panels of judges, including three in 2019. What did it mean for the translation landscape when this award came back onto the scene after decades of dormancy?

Jaquette: The reinstatement of the award in 2018 was incredible validation for translated literature in this country, placing it alongside literature written in English at the highest level. Of course, other national prizes for translated literature—the Best Translated Book Awards, the PEN Translation Prize, and ALTA’s own National Translation Award—have existed for many years, but none with the reach and prominence of the National Book Awards. The award, and the fact that it honors both translator and author, are a powerful statement of the National Book Foundation’s belief in the importance of international literature. I’ll add that the NBF does excellent public programming in addition to bestowing awards and that I’m excited to see how they’ll be able to get translated literature into the hands of readers who might not have previously considered it.

Esposito: Could you name a few books that strike you as emblematic of the future of translation and tell me why?

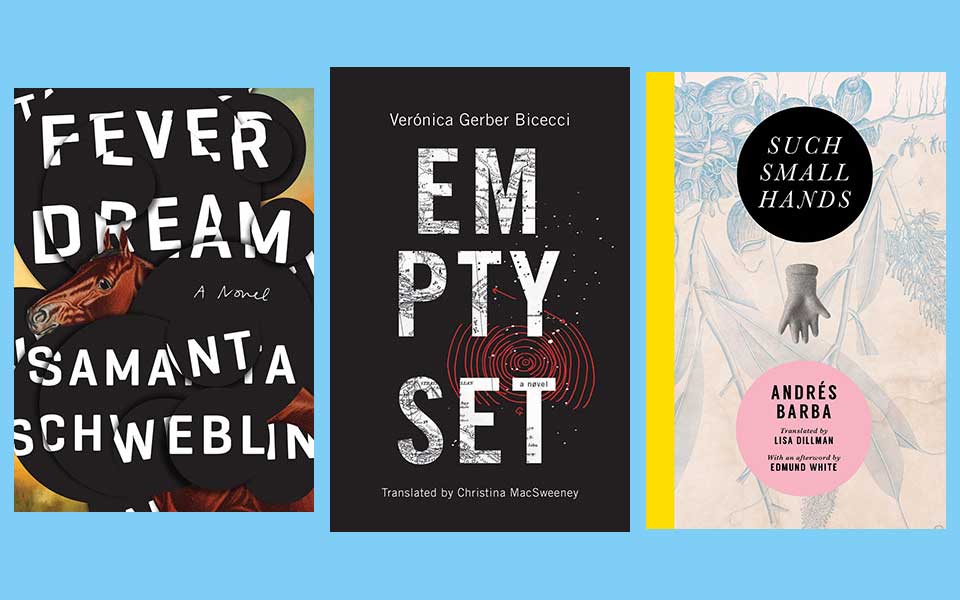

Jaquette: Such Small Hands, by Andrés Barba, translated from the Spanish by Lisa Dillman, is a title that first comes to mind. The novel is a dark, fast-paced, electrifying read about a young girl who ends up in an orphanage, alternating between her perspective and a chorus of other girls who all speak as one. It’s a book you can read in one sitting and emerge from it wondering what just happened to you. One of the first books published by Transit Books, it immediately established them in my mind as a publisher unafraid to take on unconventional but dazzling titles. More generally, I think that books which incorporate interdisciplinary elements represent translation’s ability to transcend expectations: Empty Set, by Verónica Gerber Bicecci, translated by Christina MacSweeney, for example, which incorporates drawings. I also can’t help but mention Fever Dream, by Samanta Schweblin, translated by Megan McDowell, as emblematic of the future of translation: it’s a book that bridges literary and genre writing and sits somewhere between novella and theatrical play in terms of form.

Esposito: When we’re talking about books that bridge genres or otherwise fill spaces that haven’t necessarily been filled previously, it’s important to think about needs that we may not currently be aware of. Any field can develop its own fixed ideas or things that it has forgotten to pay attention to. What would you say are the translated literature community’s blind spots?

Diversity in our field is still very much a blind spot: both in terms of who gets translated and who is doing the translating.

Jaquette: I believe the disconnect between members of the translated literature community (translators, booksellers, librarians, reviewers, and so on) is a real blind spot but also a real opportunity moving forward. Diversity in our field is still very much a blind spot: both in terms of who gets translated and who is doing the translating. And as for translators themselves, I think there is still much work to be done in terms of better working conditions. As Julia Sanches, Alex Zucker, and other colleagues working with the Authors Guild’s new Translators Group have pointed out, the number of literary translators who are able to make a living doing this work full-time is very small. If the vast majority of practicioners in the field are unable to dedicate themselves to it full-time, that limits the opportunity for professional growth and development as translators.

Esposito: I agree that the translation field isn’t nearly diverse enough. It’s ironic that a community which seeks to promote a more vibrant and complex culture representative of people all over the world is mostly white and upper-middle-class. Beyond paying more attention to diversifying the socioeconomic status of translators and publishers, what other sorts of diversity do we need more of going forward?

Jaquette: As you say, translation is an overwhelmingly white field: an Authors Guild survey from two years ago found that 83 percent of working translators are white. Those numbers are even starker when one considers that people of color are more likely to grow up with more than one language: clearly, our field is actively keeping so many bilingual and multilingual potential translators out. The field of translation, like publishing, and like our country more broadly, has a long way to go both in terms of recognizing the exclusionary practices and norms that contribute to that and in terms of active and meaningful inclusion. We also need more translations from non-European languages. There is far more structural and institutional support and funding for literature from European countries and from European languages, which means that publishers need to work harder to find books beyond that.

The field of translation, like publishing, and like our country more broadly, has a long way to go both in terms of recognizing the exclusionary practices and norms that contribute to that and in terms of active and meaningful inclusion.

Esposito: What other things would you like to see more of?

Jaquette: Along those lines, I would love to see more professional support for midcareer translators. More translation collectives, too: in recent years we’ve seen a real proliferation of small, local translation collectives (over at the ALTA blog, you can see a collectives interview series curated by Jeremy Tiang). Translators tend to be very generous and supportive of one another, perhaps because institutional support is quite limited.

Esposito: Agreed, collegiality in this field is one of its strong points, and this is something that makes a career in translation tenable. To wind up this conversation, I’d like to ask you about one trend that you think we’ll be paying attention to for years to come.

Jaquette: It’s been exciting to see more translated literature outside the bounds of literary fiction: more nonfiction, more humor, more children’s and young-adult literature in translation. I think that’s a trend we’ll see continue over the next few years. After all, as translators before me have said: translation isn’t a genre, even if we often treat it as such. Most of the books translated into English fall into the category of literary fiction, but there’s much more out there waiting to be translated.

October 2019