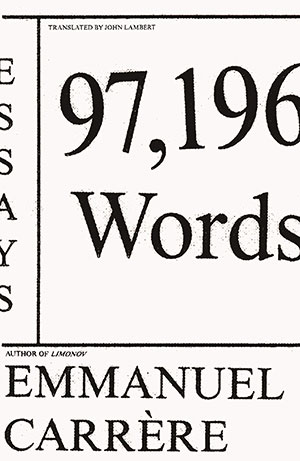

97,196 Words by Emmanuel Carrère

New York. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 2019. 304 pages.

New York. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 2019. 304 pages.

Kafkaesque is bureaucracy and red tape and all such things, of course, but more profoundly still it is the overlap between life and writing, reality and fiction—which is indeed the former, too, but in a different guise. It is because Josef K. and his peers wander into this mythico-juridical domain where life is cut to size on a legal bed of Procrustes, and thus that the transformation of life to fiction occurs within Kafka’s pages, that accordingly the many unrealities outside of them attain an eerie, tangible quality.

This and nothing less is the horizon to which all of Emmanuel Carrère’s writing strives, as he himself imagines in the vibrant little essay at the heart of this volume of essays, on “The Statement of Randolph Carter” by H. P. Lovecraft, with the following vision of reading: “The last words are so dreadful that they petrify like the Gorgon. And for the one who reaches them it’s no longer possible to wake up, the dream is over, it’s reality and this reality is ghastly. You will get there soon. You’re there. You’re there.”

At this point, there, where the reader is exposed in their very seat at the edge of the Tartarus, reading is no longer contained within a hermeneutical loop but manifests itself as its very own taking place. There is a doubleness to being there; an immediate literary and philosophical transposition that Carrère indicated the contours of in his incredible, eponymous novel as “the Kingdom” (2014; Eng. 2017). In The Kingdom, the overlay was of the worlds of believer and unbeliever in the experiences of religious conversion and apostasy.

The same overlay, superimposition, or resemblance is what the essays collected in 97,196 Words mean to bring out. Carrère consistently paints himself into the picture; a ploy that is his hook, his key to unlocking the truth of all his subjects. With Carrère’s immersion comes his casual tone (though the catchword “okay” comes courtesy of his translator as it corresponds to d’accord, admettons, alors, bon, and voilà) as well as the masculinity of his presence as a father and a lover always paired with the cerebral role of the writer.

Finally, Carrère arrives at Calais—one of the epicenters of the European humanitarian catastrophe destroying the lives of refugees—where he receives a letter asking what exactly he is doing there. For Calais, there means le jungle, the refugee camp that is the fissure dividing the city politically and socially and from which its official residents can have no reprieve. For Carrère, too, there is no reprieve: he doesn’t tell the story of his visit to le jungle. For the one who goes there the dream is over. This is reality, and reality is ghastly. You will get there soon. You’re there. You’re there.

Arthur Willemse

University of Maastricht