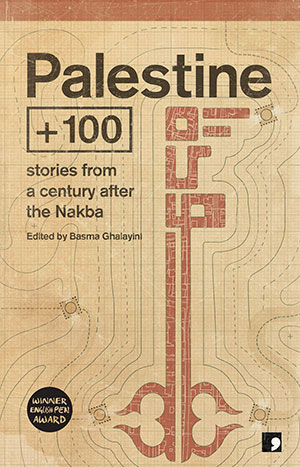

Palestine +100: Stories from a Century after the Nakba

Manchester, UK. Comma Press. 2019. 222 pages.

Manchester, UK. Comma Press. 2019. 222 pages.

The twelve stories in Palestine +100 present radically different visions of Palestine in 2048. Technology dominates, particularly virtual reality and drone policing, with interference from the supernatural. In “The Key,” by Anwar Hamed, translated by Andrew Leber, an invisible wall erected around Israel is disrupted by Palestinian ghosts returning home. Characters in every story have impaired or supernatural sight. A young woman in “Song of the Birds,” by Saleem Haddad, glimpses the decayed and wretched world that virtual reality obscures. In Emad El-Din Aysha’s “Digital World,” virtual reality has a positive effect, demolishing cultural and linguistic walls between Palestine and Israel.

If isolation is untenable, so is assimilation. The study of history is forbidden in “The Association,” by Samir El-Youssef, translated by Raph Cormack, but the protagonist uncovers an underground movement that defends the right to remember. “N,” written by Majd Kayyal and translated by Thoraya El-Rayyes, offers an alternative to coexistence: parallel dimensions that enable Palestinians and Israelis to occupy the same territory. Forced to settle permanently in one dimension, the narrator’s friend, Salem, chooses Israel. The narrator reflects that Salem “used to talk about our responsibility—even if we were the victims—towards the humanity of our enemies.” The narrator isn’t so charitable. When trying to buy a grouper, he discovers that the fish is hard to catch. Not enough seacoast was preserved in the partition. He thinks, “How did we let the issue of the sea pass? Two weeks for a grouper. Our blind damn hearts.”

The longest story in the collection unites the thematic preoccupations of the others. “The Curse of the Mud Ball Kid,” by Mazen Maarouf, translated by Jonathan Wright, reads like a riddle. The narrator, the last living Palestinian, lives in a box designed to contain the collective energy of the Palestinian dead, which resides in him. His friend, an Israeli orphan named Ze’ev, regularly shoots him in the eye to disperse some of that energy. The narrator survives because of a superhero alter ego, Robomicrobe, that he invents to heal his dying sister. The idea of Robomicrobe brings him back to life but doesn’t save his people. “I thought God would answer my prayers so long as I always behaved like a superhero,” he thinks. “But my sister died, and I didn’t become a superhero.”

This is a collection of frayed ends, of solutions that can’t last. The authors offer moments of insight and humor that suggest if nothing is certain about the future of Palestine, at least everything is possible.

Sara Ramey

University of Arkansas