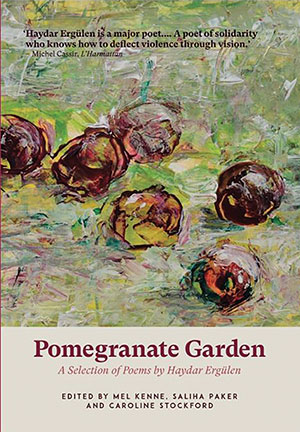

Pomegranate Garden by Haydar Ergülen

Cardigan, UK. Parthian Books. 2019. 115 pages.

Cardigan, UK. Parthian Books. 2019. 115 pages.

Haydar Ergülen, born in 1956, is from a stripe of contemporary living poets who have deftly streamed their peculiar national consciousness to the level of global literature (see WLT, March 2018, 20). Turkey, famous for raising Nâzim Hikmet to world readership, is rich soil for new poetics.

Pomegranate Garden is an achievement in translation as much as it is an important contribution to international poetry. Ten years in the making—and against the political irascibility of Turkey’s censorial culture—thirteen translators collaborated on Ergülen’s first book in English. In 2006 the project to translate Ergülen into English began at the Cunda International Workshop for Translators of Turkish Literature. With twenty-one books of poetry published in Turkey, Ergülen was ideal as a well-rounded academic in a long line of eccentric Turkish poets.

As one of the translators, Saliha Parker writes in her foreword to Pomegranate Garden: “At the core of Ergülen’s work is the pervasive sense of poetry-writing as an inseparable part of life. . . . Poetry, goodness and love is indispensable to the poet as a human being.” Parker is eminent in Istanbul as a professor of translation studies at Boğaziçi University. She worked with twelve other translators, including Mel Kenne, a previous collaborator on the magical realism of Turkish novelist Latife Tekin.

Ergülen has a broad poetic range. Pomegranate Garden features works from 1982 to 2019. Pomegranate Garden delights in prose poetry, symbolism, free verse, narrative, premodern classicism, and the occasional mystic spiritual. But arguably, Ergülen best succeeds at what Parker notes as his “down-to-earth concerns of humanity itself.” In his poem “Borrowed Like Sorrow” (2005), he writes, “Mornings are tough / much more so than poetry.” His quotidian commentary becomes profound in his elegy to the Armenian journalist Hrant Dink, written the year he was assassinated. “In truth we are neither Turks, nor Kurds, nor Armenians, / ours such a ‘father,’ Hrant, we are all orphans,” Ergülen writes in “Gazel of Orphans” (2007).

He is unabashedly joyful about his work, in an autobiographical way that lends itself to ecstatic, performative poetry. “I love a bit of Haydar and a bit of Ergülen poetry,” he wrote in his poem “I Could Never Be an Evening!” (2011). In such poems, and throughout Pomegranate Garden, there are references to other famous Turkish poets, like Attilâ İlhan, Cemal Süreya, and Oktay Rifat. He does not mention them out of competitive spite, as is common among poets in Turkey, but in solidarity. Ergülen celebrates poetic universality, as an essential human activity for all. “[T]he world is poetry’s garden too,” he writes in his long poem “On Things That Are Falling Asleep” (2011). It is an apt metaphor for the world as an open pomegranate of countless poems.

Matt A. Hanson

Istanbul, Turkey