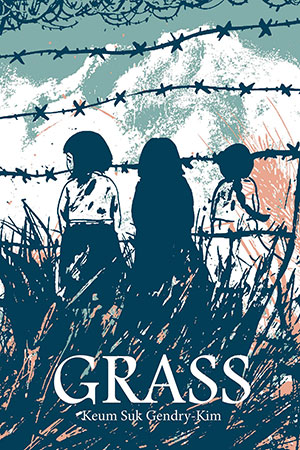

Grass by Keum Suk Gendry-Kim

Montreal. Drawn & Quarterly. 2019. 480 pages.

Montreal. Drawn & Quarterly. 2019. 480 pages.

An oral history in comics form, Grass tells the story of Korean national Lee Ok-Sun, who, at the age of fifteen, was abducted into sexual slavery as one of tens of thousands of “comfort women” serving (being raped by) Japanese soldiers during World War II. Sensitive and understated, this rendering of one woman’s horrific experiences—both during the war and after—does not shy from hard images. The artist-author’s pairing of spare words with lovely black-and-white ink artwork demonstrates that for some things there are not only no words but also really no images. Pages alternate between clearly defined scenes, partial images, and illegible smears of ink; between light and darkness; full-page bleeds and boxy frames. Natural imagery—trees, grasses, stars, flowers—scatter through and cradle the narrative, reminders of the inaccessible beauty and open spaces that surround these women’s closed and difficult daily lives.

At times, the narrative moves very slowly. When this works best, the pace demands the reader stay in a difficult experience or offers quiet spaces for reflection. Yet, perhaps the result of documenting a life derailed, in this slow pace the story itself can feel a bit lost. The art is skillful and imaginative; the tale could use a stronger throughline—and a more nuanced development of who Lee became as an individual. While Gendry-Kim builds a clear picture of a survivor, deeply admirable for her candor about the injustices done to her and others, I still feel I hardly know her.

At one point the author pushes Lee, asking whether there might have been “better” men among all that she encountered. But Lee says no. Instead she offers examples of the many men who betrayed her trust—including her husband of fifty years. This isn’t a story with a happy ending, and it’s a story that still touches sore places.

In the afterword, the author wonders why she feels the need to add this particular narrative to the many others already available. And yet. Despite international acknowledgment of the history of comfort women, the subject still provokes controversy. In 2018 Japan officially replaced the terms “wartime forced laborers” and “sexual slaves” by “wartime laborers” and “women who worked in wartime brothels, including those who did so against their will, to provide sex to Japanese soldiers.” And in November 2019 a Japanese film festival tried to cancel the screening of a film on “comfort women”—they reversed course after protests.

If it is a story less sharp for being under pressure, Grass nevertheless adds another humanizing narrative thread to history. Perhaps there is power, after all, in the very accretion of such individual voices.

Alison Mandaville

California State University, Fresno