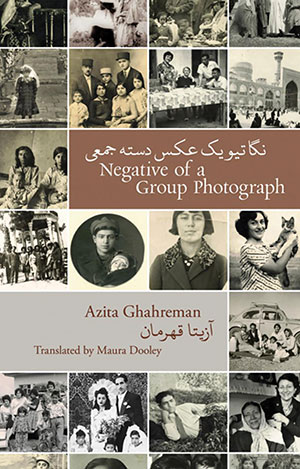

Negative of a Group Photograph by Azita Ghahreman

Eastburn, U K. Bloodaxe Books (Dufour Editions, distr.). 2018. 119 pages.

Eastburn, U K. Bloodaxe Books (Dufour Editions, distr.). 2018. 119 pages.

Negative of a Group Photograph includes thirty Persian poems by Azita Ghahreman with parallel English translations by Maura Dooley in collaboration with Elhum Shakerifar. The collection offers a fine view of Ghahreman’s introspective and sometimes inventive poetry, but its back cover makes a puzzling claim that Ghahreman is “the leading Iranian poet.” It’s unclear what the poet might be imagined to lead, but Ghahreman has not, to the best of this reviewer’s knowledge, led poetry in terms of sales, popular reception, or critical acclaim in Iran or elsewhere. That obvious misnomer sets an unfortunate tone for the book. The poet could well have been commended for publishing five collections previously, for garnering institutional support in Sweden, her country of exile, and for finding a capable English translator in Dooley, all without recourse to hyperbolic marketing. But perhaps more to the point, the exaggerated claim seems to assume that English readers are and will remain ignorant of how Persian poetry is alive and well, with a diverse community of poets who continually produce exciting new work in countries like Iran and Afghanistan and their diasporas.

Nonetheless, Ghahreman’s poetry takes a more balanced self-view. Her poetic voice often joins in conversation with her peers, as in the collection’s titular poem, which is dedicated to the “memory of the poets Ghazaleh Alizadeh and Nazanin Nezam Shahi” and recalls how their lives and the speaker’s converged for a time: “I am younger in this photograph, / younger than anything I’ve ever written, / and I am the third missing person.”

Ghahreman’s poems can also be commended for lending themselves well to translation. For one, while poets who experiment with classical forms pose an array of aesthetic challenges to the translator—see, for example, Dick Davis’s wonderfully erudite translations of Fatemeh Shams—Ghahreman writes primarily in free verse, allowing a translator like Dooley to more or less replicate the same structure on the opposite side of the page without having to accommodate for rhyme or metrical constraints. Thematically, too, Ghahreman’s world extends beyond national borders, her memories inhabited with “photos of Oppenheimer, Lumumba” in a poem like “Glaucoma.” In fact, one hears reverberations of world poetry throughout the collection. Neruda’s “Explico algunas cosas” echoes in Ghahreman’s “Negative of a Group Photograph” when the poetic voice addresses the aforementioned Alizadeh and Shahi: “For you must remember Ghazaleh? . . . For you must remember Nazanin?” Likewise, Ghahreman’s “Red Bicycle,” especially in Dooley’s translation, recalls William Carlos Williams’s wheelbarrow upon which so much depends: “I still dream / of my red bicycle / on the green shores of summer.”

Dooley’s translations, however, do not always seize upon the best opportunities to capture the poems’ universal dimensions. One such missed opportunity appears every time Dooley fails to translate the word “fārsi” from the original language: “lovingly, I wrote the snow in Farsi”; “until Farsi finds the courage to speak with the heart of a whale.” Of course, many of us use the word “Farsi” in everyday speech to refer to the language spoken by contemporary Iranians. But a poetry translation should aspire toward a more literary and historically accurate use of English. In Ghahreman’s language, fārsi denotes the language of her own poetry and her mother tongue. It denotes the same language in which Omar Khayyam wrote the Rubaiyat made famous in English by Edward Fitzgerald just as it does the language in which Rumi composed his masterpieces beloved by so many world literature enthusiasts today. The English name of Khayyam’s and Rumi’s and therefore Ghahreman’s language is Persian. It is a language that has been named, studied, and translated at English-speaking universities since at least as early as the seventeenth century.

Mistranslating the word “fārsi” as “Farsi” ignores the long-standing poetic exchanges between English and Persian just as it undermines the vibrant and ever-evolving literary tradition in which Ghahreman’s voice represents one among many.

Samad Alavi

University of Oslo