Nganajungu Yagu by Charmaine Papertalk Green

Melbourne. Cordite Books. 2019. 73 pages.

Melbourne. Cordite Books. 2019. 73 pages.

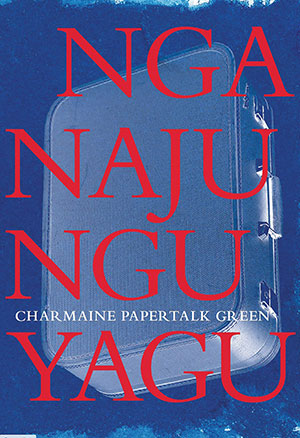

Before opening Nganajungu Yagu, readers see the image of an old-fashioned suitcase over which the author’s name and book’s title are superimposed. The title, from the Wajarri language, means “my mother,” the author tells us. What are the implications: Is Nganajungu Yagu to be a book of tragic travelogues undertaken in mostly lost indigenous tongues, Charmaine Papertalk Green versing and traversing brutally colonized lands? Or does the code-mixing in this book (between Wajarri, Badimaya, and English) imply language as a portmanteau, comporting disempowerment for indigenous language users in epistemically violent colonial contexts? Or is this writer working interlinguistically against inheritances bequeathing disconnection in a monoculturally imperialized place, as if to send an epistle issuing a set of instructions on the means by which Aboriginal Australians might fight back against a version of “Australia” that historically and systematically displaces and dispossesses indigenous peoples?

In her preface, the author explains the book’s cover image, the letters from forty years ago sent to the poet by her mother “protected in my red life-journey suitcase. . . . [The book is] inspired by Mother’s letters, her life and the love she instilled in me for my people and my culture.” Nganajungu Yagu is spliced with fragments from those letters, to which the poet responds in short bursts of autobiographical nonfiction, and this structure enables her to divest poems that speak of a family drama constituted within an overtly and infrastructurally racist Australia. Papertalk Green guides readers through often tragic scenes of forced institutionalization, domestic violence, eviction, poverty, substance abuse, and welfare dependency, but, throughout, her mother’s letters show how “being grounded includes strong connection.” Despite the systemically organized impoverishments her family confronts, they nonetheless remain bonded, and therein this book remains a work of unbroken fealty, a powerful statement attesting not only to oppression but, despite it all, prodigious hope.

Papertalk Green makes clear she is writing “during invasion,” and these texts are indeed a space in which indigenous Australians are to be “ke[pt] visible.” In this often metareflexive book, writing “about the blood they spilt . . . honors ancestors’ memories”; it also instructs current and future Aboriginal Australian writers that writing “about the land they stole . . . shows [colonizers as] savage thieves.” This book is not only a paean to matrilineal connection, then (though most certainly it is this); Nganajungu Yagu is also an instruction manual inviting future interventions—to use a Wajarri word, the book fomenting a kind of Wanggajimanha or “talking together”—that might insistently speak back against the official irradiations of a whitewashed Australian history.

Papertalk Green shows how not to be “blinded by lies,” and this important book retrieves and revivifies language, revealing acutely the truth of how the “treatment of our mob . . . is a horror movie.”

Dan Disney

Sogang University (Seoul)